中文导读

互联网时代,报纸行业传统盈利模式受到挑战,如何让读者在互联网时代为新闻付费是主流报纸都在试图解决的问题。主流报纸试图通过对数字订阅用户收取费用和数字广告而盈利,但这种措施面临各种挑战,亟待解决。

The first in the three-part series on journalism’s future examines how leading American newspapers got readers to pay for news in the Internet era

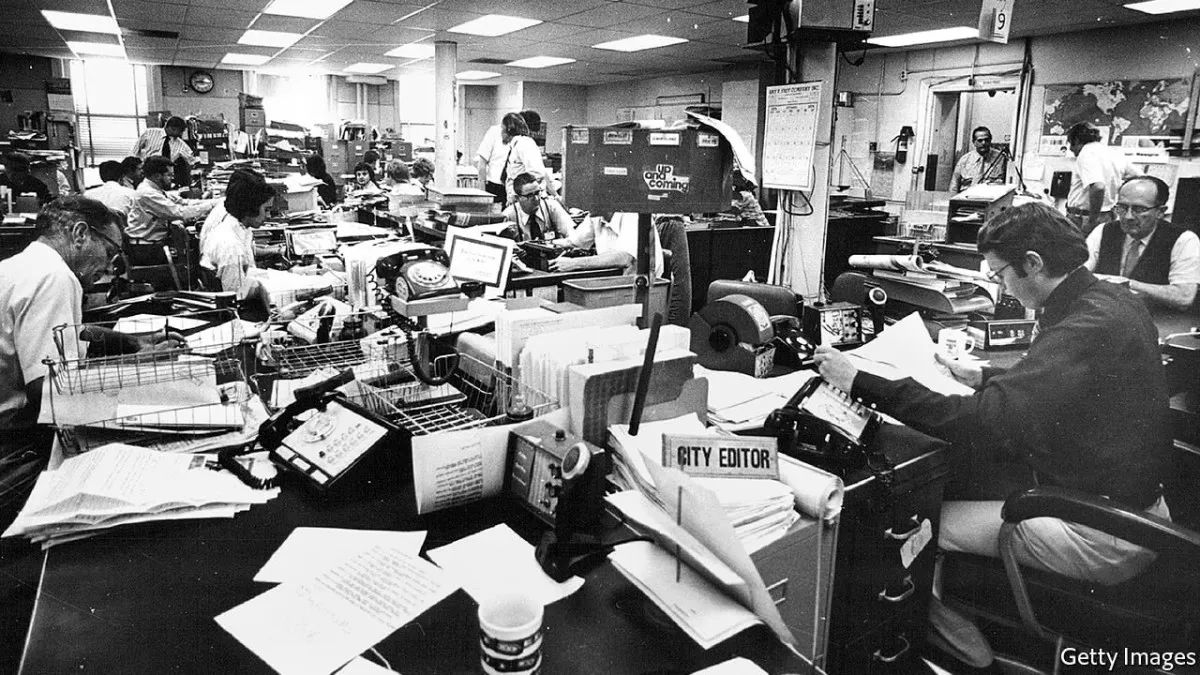

SOMETIMES it feels like the 1970s in the New York Times and Washington Post newsrooms: reporters battling each other to break news about scandals that threaten to envelop the White House and the presidency of Donald Trump. Only now their scoops come not in the morning edition but in a tweet or iPhone alert near the end of the day.

It is like old times in another way: both newspapers are getting readers to pay, offsetting advertising revenue relinquished to the internet. After years of giving away scoops for nothing online, and cutting staff, the Times and Post are focusing on subscriptions—mostly digital ones—which now rake in more money than ads do.

Their experiences offer lessons for the industry in America, although only a handful of newspapers have a chance at matching their success. A subscription-first approach relies on tapping a national and international market of hundreds of millions of educated English-language readers and converting a fraction of those into paying customers. With enough digital subscribers—Mark Thompson, chief executive of the New York Times, believes his newspaper can get to 10m, from 2m today—the subscriptions-first model could (in theory) generate more profits than business models dependent on print advertising used to.

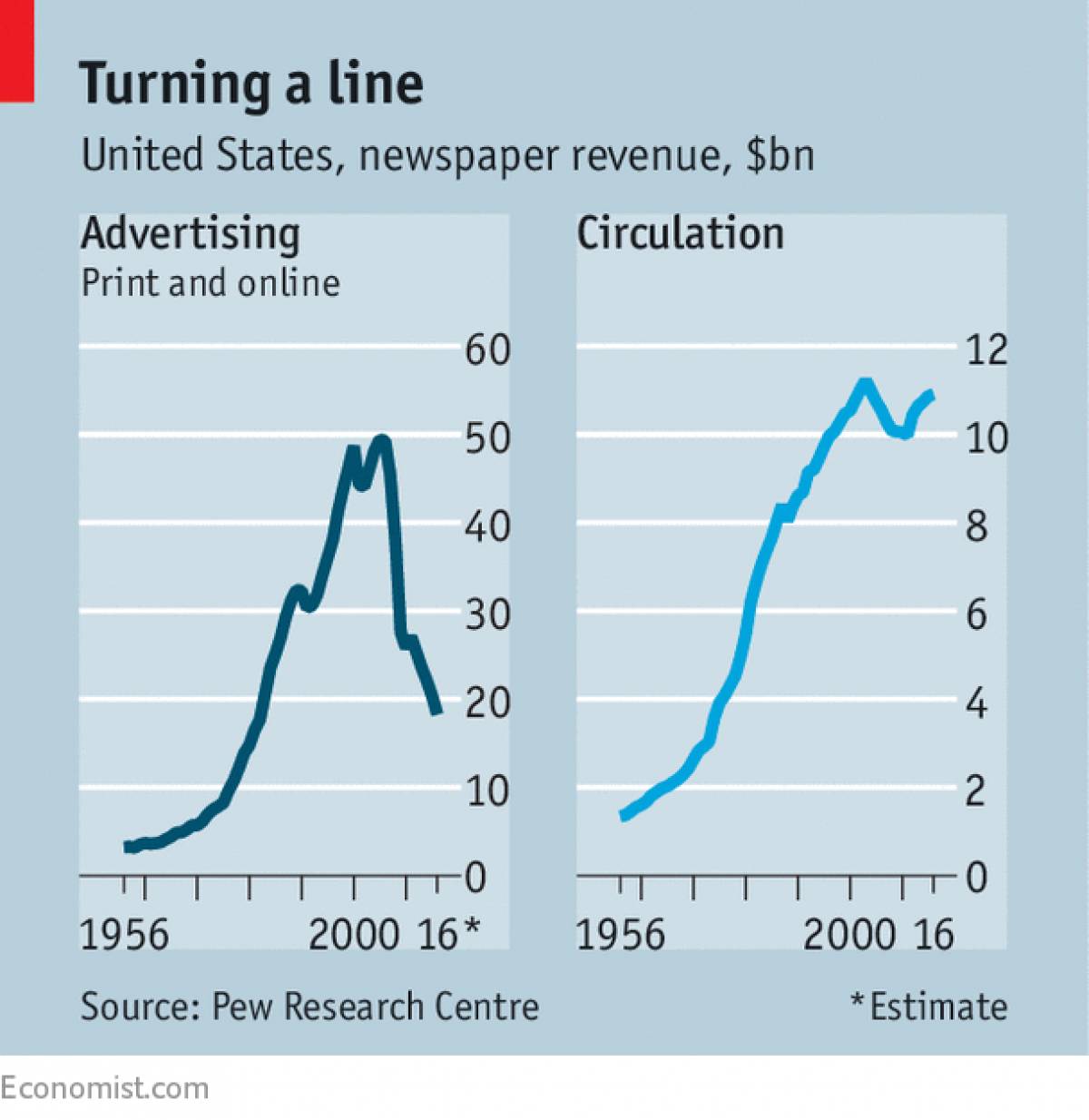

Such optimism is hard to summon after two decades of accelerating decline. In that period American newspapers lost nearly 40% of their daily circulation, which fell to 35m last year, estimates the Pew Research Centre. Annual ad revenues have shrunk by 63%, or $30bn, just in the past ten years (see chart). Newsrooms have shed 40% of reporters and editors since 2006. High returns on equity turned into single digits, losses or bankruptcy.

Like Detroit carmakers before the arrival of the Japanese, in pre-internet days newspapers flush with profits from a captive market grew lazy and complacent. Some big-city papers, like the Philadelphia Inquirer or the Baltimore Sun, splurged on foreign bureaus and fluffy suburban sections whether or not readers wanted them; classified ads alone covered these costs many times over. Now such newspapers are struggling to remain relevant to diminished readerships. A tier below, hundreds of local ones are dying or turning into advertiser sheets; newspaper chains, some managed by investment funds, have snapped up many of them, maintaining high profits by sacking journalists.

From the ashes of newsprint

The Times and Post have been buffeted by the same forces. But now each is in turnaround. The Times has doubled its digital-only subscribers in less than two years; the Post has managed the feat in ten months, and now has more than 1m. Both have staunched losses. Revenue at the Times had fallen by more than 20% in three years to less than $1.6bn in 2009; this year they are on pace to climb back above $1.6bn, led by digital subscriptions. (Return on equity still fell, to 3% last year from 37% in 2001.)

The Post had also been losing millions before Jeff Bezos, boss of Amazon, bought it in 2013. The newspaper is now privately held and does not disclose revenues and profits, but Fred Ryan, the publisher, says both are growing and the newspaper is on track for its most profitable year in a decade. The Wall Street Journal added more than 300,000 digital subscriptions in the year to June, but a sharp fall in advertising crimped revenues by 6% at Dow Jones, the division of News Corp, Rupert Murdoch’s media empire, that houses the newspaper.

How have they done it? Early attempts by newspapers to put up digital “paywalls” floundered, and met with derision from critics and competitors vaunting the internet’s ability to generate huge audiences for free content. How could anyone hope to attract paying digital customers when they could go elsewhere online for free?

The Times hit upon the answer in 2011, when it introduced a metered paywall, something the Financial Times was also trying. Visitors to the website could read a few free articles a month, after which they would be asked to pay. This approach is now standard across journalism (including at this newspaper), but it was controversial at the time. At News Corp Mr Murdoch erected a hard paywall at all his newspapers in the belief that giving away his product online would cripple the more profitable print editions. Those suffered anyway, and he later dropped the paywall at the Sun, a tabloid, and has allowed some flexibility at the Journal. Softer paywalls have created funnels to suck in customers.

On a whiteboard in Mr Thompson’s office at the Times is a diagram to illustrate the approach. At the top, where the funnel is widest, are all those who visit its digital site. (In September 104m people in America did so, according to comScore.) At the narrow end are its 2m paying digital-only subscribers (plus 1m print subscribers). Mr Thompson’s main preoccupation is to tweak the “geometry of the funnel” to shift more people from free to paid. At the Post, Mr Ryan is also busy funnelling.

The job of funnel mathematician did not exist at newspapers six years ago. Now it is one of the most important functions a digital site has. The Times and Post conduct numerous tests of different ways to trigger the paywall, for instance if a visitor returns to the same columnist. It is A/B testing like at a technology company, Mr Ryan says, except it is more like “A to Z testing”. The Post has settled on three site visits a month before hitting the paywall, which means 85% of visitors will not encounter it. The other 15% are asked to subscribe at the introductory rate of 99 cents for the first four weeks.

Both newspapers sift through data about what visitors do just before stumping up. The Post looks at the “month zero” of a reader’s pre-subscription activity on the site. Mr Ryan credits the effort, which began a year ago, with helping to convert more visitors to subscribers this year.

Another factor has helped the two papers: Mr Trump. Since his election they have revived an old rivalry, vying for sensational scoops, sometimes several in a day. Mr Trump’s attacks on both newspapers—“the failing New York Times”, “more fake news from the Amazon Washington Post”—have almost certainly helped their bottom lines. His presidency has created an urgency around news that has made old-fashioned journalism more in vogue than it has been probably since Watergate. Fake news shared on social media has reinforced a feeling that real news costs money.

From the ashes of newsprint

The newspapers’ bosses agree Mr Trump has been good for business, but add they were ready for the moment. As Mr Bezos is fond of saying, “you can’t shrink your way to profitability”. He invested in the Post after buying it, hiring technologists to improve its digital presence. He has also added reporters (the Post now has 750 newsroom employees and counting). Marty Baron, editor of the Post, added a rapid-response investigative team of eight people this year. Dean Baquet, executive editor of the Times, has expanded the Washington bureau twice since the election. (The Times paid for new reporters in part by cutting dozens of other editorial jobs.)

The subscription-first approach justifies adding reporters. By increasing the quality of the product, newspapers hope to lure subscribers. But it is not clear others can replicate that virtuous circle so easily. Many regional papers are nurturing digital subscribers—they all have their funnels now, too—but are doing so on a much smaller scale. They will have to come up with other ways to make money to survive. “They have to do everything,” says Jay Rosen, a professor of journalism at New York University.

By “everything” media experts like Mr Rosen mean ending a reliance on two traditional sources of revenue: ads and subscriptions. At regional papers, unlike the national ones, prospects for both are limited by the size of the metropolitan market. Savings from printing fewer copies are small—printing and distribution costs are mostly fixed—so they must either cut staff or find other ways to make money. This may include staging trade fairs, offering memberships with perks, even e-commerce partnerships. Such sidelines help to ward off staff cuts; to be a community hub, newspapers must also cover communities effectively. They may forgo costly (and wasteful) foreign and national bureaus. But to attract local readers, they must provide relevant coverage of city halls, courthouses, police precincts or schools.

Take the Star Tribune in Minneapolis, a privately owned newspaper which has managed to keep the newsroom humming along. Almost annually Mike Klingensmith, the publisher, and a few of his senior executives meet with their counterparts at the Dallas Morning News, Boston Globe and one or two other independently owned newspapers. They sign non-disclosure agreements and then share ideas about how to make money. In the past year Mr Klingensmith has adopted three of them, adding several million dollars in revenue: organising an advertiser fair to attract new clients; putting on a consumer travel show; and starting a glossy quarterly print magazine.

That gives the Star Tribune’s funnel mathematician a product to sell. Patrick Johnston, a digital executive poached from Target, the retail store, and his boss Jim Bernard, a former executive at Marketwatch, a business-news website, explain how a local newspaper’s funnel vision is different. They are, like the big papers, interested in the visitors who they call “intenders”, people whose browsing behaviour suggests they may be ready to subscribe. But whereas many visitors to the Times and Post are potential intenders, the Star Tribune can dismiss about 50% of its online traffic—the “grazers” from outside Minnesota who clicked a link—and focus on the other half. Reducing friction is vital; they have got 25% more intenders to subscribe since installing PayPal as a payment option.

Hold the presses

The downside to the ease of online subscriptions is the ease of cancelling them. Newspapers guard their rates of digital churn closely because they are so high—despite an all-out effort the Star Tribune keeps only one in two subscribers after 14 months (the Times and Post numbers are better, executives there say, without giving figures). A subscriber’s early days are essential. Keeping a visitor engaged with the site is similar to getting a “guest” on Target’s website to put another item in their basket, Mr Johnston says. It also means competing with ever more rivals for people’s attention: bigger fish like the Times and Post, but also Netflix, Spotify or Candy Crush.

The virtue of digital subscriptions is that they build a deeper relationship between readers and newspapers than when distribution meant throwing broadsheets onto doorsteps. Newspapers nowadays know a lot more about their customers’ tastes. That lets them tailor the experience to readers individually, with the aim of keeping them around longer. It can be, as Mr Thompson says, an annuity for the newspaper. But the newspaper has to be worth the cover price.

——

Oct 28th 2017 | Business | 1944 words