中文导读

6月16日,电子商务巨头亚马逊宣布将以137亿美元收购美国最大的有机食品零售商全食超市。这是亚马逊迄今为止最大的并购交易,也展示了其进军零售业的勃勃野心。亚马逊高效的物流体系和全食已有的店铺、仓储体系结合下,将会对沃尔玛、Costco等竞争者产生怎样的冲击

,我们拭目以待。

The deal intensifies Amazon’s battle with the beast of Bentonville

JEFF BEZOS does not like sitting still. In his annual letter to Amazon’s shareholders this year, he warned of “stasis. Followed by irrelevance. Followed by excruciating, painful decline. Followed by death.” Competitors are toiling to avoid the same fate but it is hard to keep up. On June 16th Amazon said it would pay $13.7bn for Whole Foods, an upscale grocer known for its organic produce. Lest be accused of sloth, four days later Amazon announced a new service to let shoppers try clothes at home, for no fee, then return those they don’t like.

The news that Amazon would make clothes shopping even easier is a blow to America’s apparel chains, many of which are already in the middle of that excruciating decline. Yet it was the Whole Foods deal, more than ten times bigger than any acquisition Amazon has made so far, that caused the bigger stir.

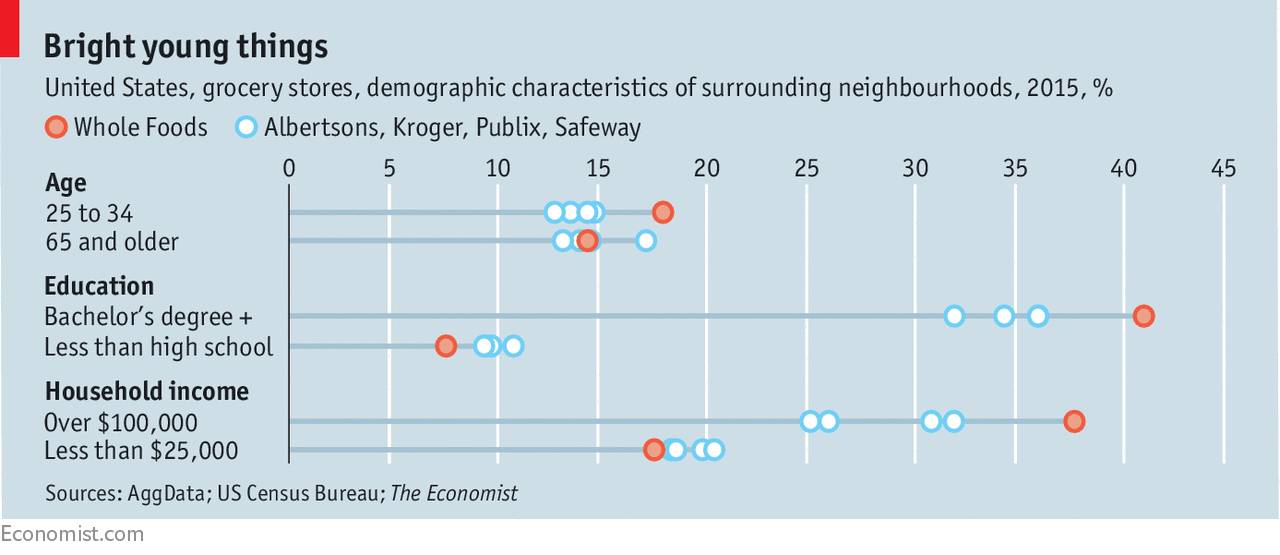

The deal’s precise impact is hard to gauge. Buying Whole Foods hardly gives Amazon a stranglehold on food and drink: the combined companies will account for just 1.4% of America’s grocery market, according to GlobalData, a research firm. The people who shop at the chain are not the mass market. They are unusually wealthy and well-educated (see chart). Mr Bezos has made no big announcements about changes at Whole Foods—drone-delivered spelt grain is unlikely to become a reality soon. Instead he simply praised its work and said “we want that to continue.”

Nevertheless, the news prompted the shares of a large group of rival grocery firms, including Walmart and Kroger, to sink quickly. As with so much about Amazon, the Whole Foods deal is important not for what it represents now but how it might transform Amazon and up-end rivals—most notably, Walmart—in future.

Up to now, grocery has been a tough nut for Amazon to crack. A growing share of office supplies and clothes are bought online, yet last year e-commerce accounted for just 2% of American spending on food and drinks. Amazon Fresh, a ten-year-old grocery-delivery service, is still in only 20-odd cities. Prime Now, a two-hour delivery service introduced in 2014, is in 31.

That is because grocery’s margins are low and its goods devilishly hard to deliver. Peaches bruise. Meat rots. Many consumers like to buy food in person: unlike choosing a battery or book, selecting a ripe tomato requires inspecting it or trusting someone who has.