How Leonardo da Vinci engineered the world’s most famous painting

Alvaro Tapia Hidalgo

LEONARDO DA VINCI liked to think that he was as good at engineering as he was at painting, and though this was not actually the case (nobody was as good at engineering as he was at painting), the basis for his creativity was an enthusiasm for interweaving diverse disciplines. With a passion both playful and obsessive, he pursued innovative studies of anatomy, mechanics, art, music, optics, birds, the heart, flying machines, geology, and weaponry. He wanted to know everything there was to know about everything that could be known. By standing astride the intersection of the arts and the sciences, he became history’s most creative genius.

His science informed his art. He studied human skulls, making drawings of the bones and teeth, and conveyed the skeletal agony of Saint Jerome in the Wilderness. He explored the mathematics of optics, showing how light rays enter the eye, and produced magical illusions of changing visual perspectives in The Last Supper.

His greatest triumph of combining art, science, optics, and illusion was the smile of the Mona Lisa, which he started working on in 1503 and continued laboring over nearly until his death 16 years later. He dissected human faces, delineating the muscles that move the lips, and combined that knowledge with the science of how the retina processes perceptions. The result was a masterpiece that invites and responds to human interactions, making Leonardo a pioneer of virtual reality.

The magic of the Mona Lisa’s smile is that it seems to react to our gaze. What is she thinking? She smiles back mysteriously. Look again. Her smile seems to flicker. We glance away, and the enigmatic smile lingers in our minds, as it does in the collective mind of humanity. In no other painting are motion and emotion, the paired touchstones of Leonardo’s art, so intertwined.

The artist Giorgio Vasari, a near-contemporary, told of how Leonardo kept Lisa del Giocondo, the young wife of a Florentine silk merchant, smiling during her portrait sessions. “While painting her portrait, he employed people to play and sing for her, and jesters to keep her merry, to put an end to the melancholy that painters often succeed in giving to their portraits.” The result, Vasari said, was “a smile so pleasing that it was more divine than human,” and he proclaimed that it was a product of superhuman skills that came directly from God.

That’s a typical Vasari cliché, and it’s misleading. The Mona Lisa’s smile came not from some divine intervention. Instead, it was the product of years of painstaking and studied human effort involving applied science as well as artistic skill. Using his technical and anatomical knowledge, Leonardo generated the optical impressions that made possible this brilliant display of virtuosity. In doing so, he showed how the most-profound examples of creativity come from embracing both the arts and the sciences.

LEONARDO'S EFFORTS TO fashion the Mona Lisa’s effects began with the preparation of the painting’s wood panel. On a thin-grained plank cut from the center of a trunk of poplar, he applied a primer coat of lead white, rather than just a mix of chalk and pigment. That undercoat, he knew, would be better at reflecting back the light that made it through his fine layers of translucent glazes and thereby would enhance the impression of depth, luminosity, and volume.

Some of the light that penetrates the layers of paint reaches the white undercoat and is reflected back through those same layers. As a result, our eyes see the interplay between the light rays that bounce off the colors on the surface and those that dance back from the depths of the painting. This creates shifting and elusive subtleties. The contours of Lisa’s cheeks and smile are created by soft transitions of tone that seem veiled by the glaze layers, and they vary as the light in the room and the angle of our gaze change. The painting comes alive.

Photograph: Dennis Hallinan / Alamy

Like 15th-century Netherlandish painters such as Jan van Eyck, Leonardo used glazes that had a very small proportion of pigment mixed into the oil. Leonardo’s distinctive approach was to apply the glaze in extraordinarily thin and tiny strokes and then very slowly, over months and sometimes years, apply additional layer upon thin layer. This permitted him to create forms that looked three-dimensional, show subtle gradations in shadows, and blur the borders of objects in a sfumato style. His strokes were so light and layered that many individual brushstrokes are imperceptible.

For the shadows that form the contours of Lisa’s face and especially around her smile, he pioneered the use of an iron-and-manganese mix to create a pigment that was burnt umber in color. “The thickness of a brown glaze placed over the pink base of the Mona Lisa’s cheek grades smoothly from just 2–5 micrometers to around thirty micrometers in the deepest shadow,” according to a Nature article about a recent study using X-ray-fluorescence spectroscopy. The strokes were applied in an intentionally irregular way that served to make the grain of the skin look more lifelike.

DURING THE YEARS when he was perfecting Lisa’s smile, Leonardo was spending his nights in the depths of the morgue at the Hospital of Santa Maria Nuova, near his Florence studio, peeling the skin off cadavers and studying the muscles and nerves underneath. He became fascinated by how a smile begins to form, and he analyzed every possible movement of each part of the face to determine the origin of every nerve that controlled each facial muscle.

Leonardo was especially interested in how the human brain and nervous system translate emotions into movements of the body. In one drawing, he showed the spinal cord sawed in half, and delineated all the nerves that ran down to it from the brain. “The spinal cord is the source of the nerves that give voluntary movement to the limbs,” he wrote.

Of these nerves and related muscles, the ones controlling the lips were the most important to Leonardo. Dissecting them was exceedingly difficult, because lip muscles are small and plentiful and attach deep in the skin. “The muscles which move the lips are more numerous in man than in any other animal,” he wrote. “One will always find as many muscles as there are positions of the lips and many more that serve to undo these positions.” Despite these difficulties, Leonardo depicted the facial muscles and nerves with remarkable accuracy.

Leonardo tested in himself and in the cadaver how each muscle of the cheek could move the lips.

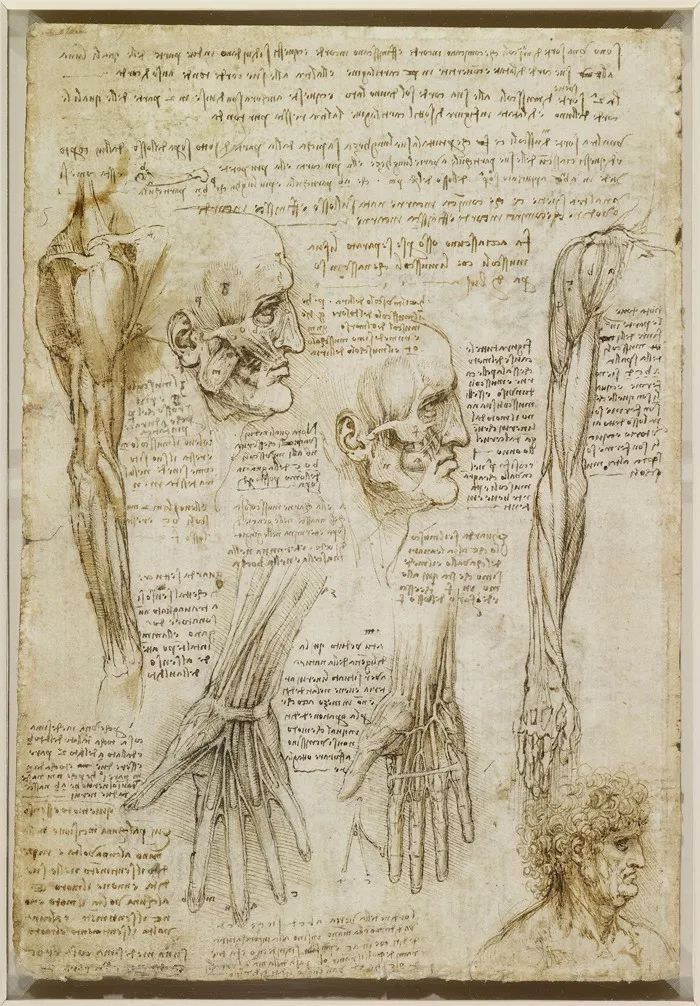

On one delightfully crammed anatomical sheet (Figure 1, below), Leonardo drew the muscles of two dissected arms and hands, and he placed alongside them two partially dissected faces in profile. The faces show the muscles that control the lips and other elements of expression. In the one on the left, Leonardo has removed part of the jawbone to expose the buccinator muscle, which pulls back the angle of the mouth and flattens the cheek as a smile begins to form. Here we can see, revealed with masterful scalpel cuts and then pen strokes, the actual mechanisms that transmit emotions into facial expressions. “Represent all the causes of motion possessed by the skin, flesh and muscles of the face and see if these muscles receive their motion from nerves which come from the brain or not,” he wrote next to one of his face drawings.

He labeled one of the muscles in the left-hand drawing “H” and called it “the muscle of anger.” Another is labeled “P” and designated as the muscle of sadness or pain. He showed how these muscles not only move the lips but also serve to move the eyebrows downward and together, causing wrinkles.

Leonardo also describes pursuing the comparative anatomy he needed for a battle painting that he was planning; he matched the anger on the faces of the humans to that on the faces of the horses. After his note about representing the causes of motion of the human face, he added: “And do this first for the horse that has large muscles. Notice whether the muscle that raises the nostrils of the horse is the same as that which lies here in man.” Thus we discover another secret to Leonardo’s unique ability to paint a facial expression: He is probably the only artist in history ever to dissect with his own hands the face of a human and that of a horse to see whether the muscles that move the lips are the same ones that can raise the nostrils of the horse’s nose.

Figure 1 (Royal Collection Trust. © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, 2017.)

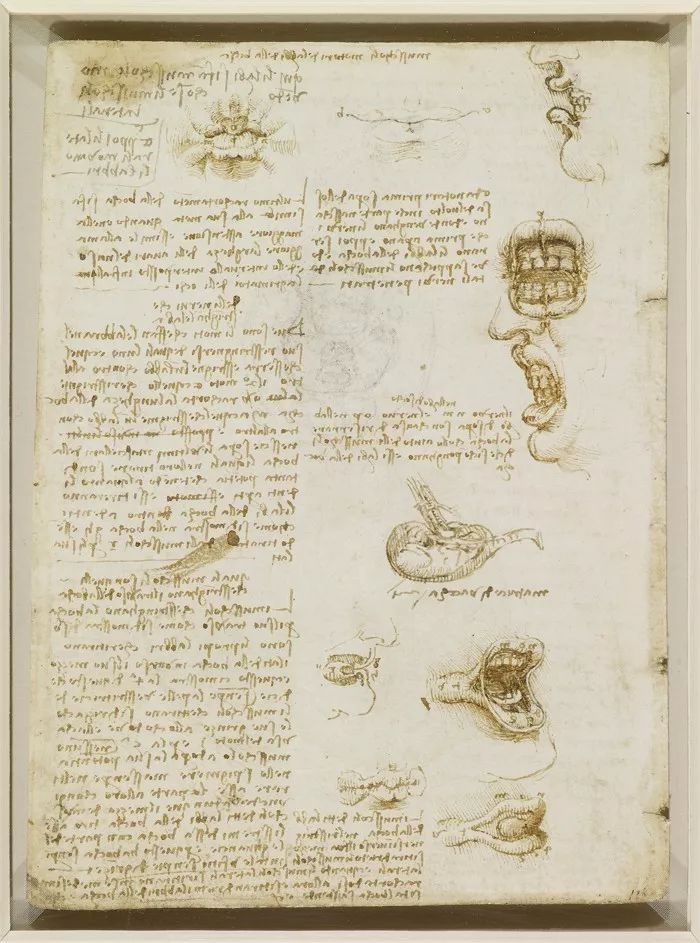

Leonardo’s excursions into comparative anatomy allowed him to delve deeper into the physiological mechanisms of humans as they smiled or grimaced (Figure 2, below). He focused on the role of various nerves in sending signals to the muscles, and he asked a question that was central to his art: Which of these are cranial nerves originating in the brain and which are spinal nerves?

His notes begin with a description of how to portray angry expressions. “Make the nostrils drawn up, causing furrows in the side of the nose, and the lips arched to disclose the upper teeth, with the teeth parted in order to shriek lamentations,” he wrote. He then began to explore other expressions. In the top-left corner of another page, he drew lips that were tightly pursed, under which he wrote, “The maximum shortening of the mouth is equal to half its maximum extension, and it is equal to the greatest width of the nostrils of the nose and to the interval between the ducts of the eye.”

He tested in himself and in the cadaver how each muscle of the cheek could move the lips, and how the muscles of the lips can also pull the lateral muscles of the wall of the cheek. “The muscle shortening the lips is the same muscle forming the lower lip itself,” he wrote. This led him to a discovery that any of us could make on our own, but it is a testament to Leonardo’s keen power of observation that he noticed it when most of us don’t: Because we pucker our lips by contracting the muscle that forms the lower lip, we can pucker both lips at the same time or the lower lip alone, but we cannot pucker our top lip alone. It was a tiny discovery, but for an anatomist who was also an artist, especially one who was painting the Mona Lisa, it was worth noting.

Figure 2 (Royal Collection Trust. © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, 2017.)

Other movements of the lips involve different muscles, including “those which bring the lips to a point, others which spread them, and others which curl them back, others which straighten them out, others which twist them transversely, and others which return them to their first position.” He sketched head-on and profile drawings of retracted lips with the skin still on, then a row of lips with the skin layer peeled off. This is the first known anatomical drawing of the human smile.

Floating above the grotesque grimaces on the top of the page in Figure 2 is a faint sketch in black chalk of a simple set of lips that are rendered in a way that is artistic rather than anatomical. The lips peek out of the page directly at us with just a hint—flickering and haunting and alluring—of a mysterious smile. Even though the fine lines at the ends of the mouth turn down almost imperceptibly, the impression is that the lips are smiling. Here amid the anatomy drawings we find the makings of the Mona Lisa’s smile.

ANOTHER PIECE OF SCIENCE that augments the Mona Lisa’s smile comes from Leonardo’s research on optics: He realized that light rays do not come to a single point in the eye, but instead hit the whole area of the retina. The central area of the retina, known as the fovea, has closely packed cones and is best at seeing small details; the area surrounding the fovea is best at picking up shadows and shadings of black and white. When we look at an object straight on, it appears sharper. When we look at it peripherally, glimpsing it with the corner of our eye, it is a bit blurrier, as if it were farther away.

With this knowledge, Leonardo was able to create an interactive smile, one that is elusive if we are too intent on seeing it. The fine lines at the corners of Lisa’s mouth show a small downturn—just like the mouth floating atop the anatomy sheet. If you stare directly at the mouth, the retina catches these tiny details and delineations, making her appear not to be smiling. But if you move your gaze slightly away, to look at her eyes or cheeks or some other part of the painting, you will catch sight of her mouth only peripherally. It will be a bit blurrier. The tiny delineations at the corners of the mouth become indistinct, but you will still see the shadows at her mouth’s edge. These shadows and the soft sfumato at the edge of her mouth make her lips seem to turn upward into a subtle smile. The result is a smile that twinkles brighter the less you search for it.

Scientists recently found a technical way to describe all of this. “A clear smile is much more apparent in the low spatial frequency [blurrier] images than in the high spatial frequency image,” according to the Harvard Medical School neuroscientist Margaret Livingstone. “Thus, if you look at the painting so that your gaze falls on the background or on Mona Lisa’s hands, your perception of her mouth would be dominated by low spatial frequencies, so it would appear much more cheerful than when you look directly at her mouth.”

So the world’s most famous smile is inherently and fundamentally elusive, and therein lies Leonardo’s ultimate realization about human nature. His expertise was in depicting the outer manifestation of inner emotions, but here in the Mona Lisa he shows something more important: that we can never fully know another person’s true emotions. They always have a sfumato quality, a veil of mystery.

LEONARDO ONCE WROTE and performed at the court of Milan a discourse on why painting should be considered the most exalted of all the art forms, more worthy than poetry or sculpture or even the writing of history. One of his arguments was that painters did more than simply depict reality—they also augmented it. They combined observation with imagination. Using tricks and illusions, painters could enhance reality with cobbled-together creations, such as dragons, monsters, angels with wondrous wings, and landscapes more magical than any that ever existed. “Painting,” he wrote, “embraces not only the works of nature but also infinite things that nature never created.”

Leonardo believed in basing knowledge on experience, but he also indulged his love of fantasy. He relished the wonders that could be seen by the eye but also those seen only by the imagination. As a result, his mind could dance magically, and sometimes frenetically, back and forth across the smudgy line that separates reality from fantasia.

Mona Lisa seems miraculously alive, conscious both of us and of herself.

Stand before the Mona Lisa, and the science and the magic and the art all blur together into an augmented reality. While Leonardo worked on it, for most of the last 16 years of his life, it became more than a portrait of an individual. It became universal, a distillation of Leonardo’s accumulated wisdom about the outward manifestations of our inner lives and about the connections between ourselves and our world. Like Vitruvian Man standing in the square of the Earth and the circle of the heavens, Lisa sitting on her balcony is Leonardo’s profound meditation on what it means to be human.

When the British needed to contact their allies in the French resistance during World War II, they used a code phrase: La Joconde garde un sourire—“The Mona Lisa keeps her smile.” Even though it may seem to flicker, her smile contains the immutable wisdom of the ages.

The Mona Lisa became the most famous painting in the world not just because of hype and happenstance, but because viewers were able to feel an emotional engagement with her. It is a brilliant depiction of reality—an alluring and emotionally mysterious woman sitting alone on a loggia—that is augmented radiantly by science and magical illusions. She provokes a complex series of psychological reactions, ones that she in turn seems to exhibit as well. Most miraculously, she seems aware—conscious—both of us and of herself. That is what makes her seem alive, more alive than any other portrait ever painted.

And what about all the scholars and critics over the years who despaired that Leonardo squandered too much time immersed in his studies of optics, anatomy, technology, and the patterns of the cosmos? The Mona Lisa answers them with a smile.

——

NOVEMBER 2017 ISSUE | 2886 words