中文导读

虽然近期伴随着联合军演,双方领导人频繁会晤,中俄显示出亲密的关系,但由于双方合作关系的不平等性,在中亚地区影响力的竞争性,国家利益以及历史原因,双方还存在着很多顾虑和猜疑,安全,经济的合作与博弈仍在继续。

Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin are cosying up. But mutual suspicions are deep.

ON JULY 21st three Chinese warships sailed into the Baltic Sea for China’s first war games in those waters with Russia’s fleet. The two powers wanted to send a message to America and to audiences at home: we are united in opposing the West’s domination, and we are not afraid to show off our muscle in NATO’s backyard. The war games were also intended to show how close the friendship between China and Russia has become—so much has changed since the days of bitter cold-war enmity that endured between them from the 1960s to the 1980s.

There has been an abundance of such symbolism in recent weeks. On his way to this month’s meeting in Germany of leaders from the G20 group of countries, China’s president, Xi Jinping, stopped off in Moscow. There his Russian counterpart, Vladimir Putin, hung an elaborate medallion around his neck: the Order of St Andrew, Russia’s highest state award. At the G20 (where they are pictured), “only two leaders in the world exuded calm confidence,” Dmitry Kiselev, a cheerleader for the Kremlin, said on his television show in reference to Mr Putin and Mr Xi. “Russia is pivoting to the east. China is turning to the west—towards Russia,” he crowed.

Since he became China’s leader in 2012, Mr Xi has visited Moscow more than any other capital city. In 2013, during a meeting in Indonesia of leaders from the Asia-Pacific region, he even attended a private birthday party for Mr Putin. Over vodka and sandwiches they talked about their fathers’ experiences in the second world war—Mr Putin’s against Germany and Mr Xi’s against Japan. In 2015 Mr Xi was the guest of honour at a military parade in Moscow that was held to mark the 70th anniversary of the war’s end, and was boycotted by Western leaders because of Russia’s war in Ukraine. Four months later Mr Putin attended a parade in Beijing celebrating China’s victory in the war against Japan. South Korea’s then president, Park Geun-hye, was the only leader of an American ally who showed up.

Fellow autocrats

Mr Xi and Mr Putin take comfort in each other’s authoritarian bent. China has copied Russia’s harsh laws on NGOs; the Kremlin has been trying to learn how China censors the internet. During Mr Xi’s recent visit to Moscow, the two leaders listened to a speech by Margarita Symonyan, the boss of Russia Today, the Kremlin’s foreign-language television channel. Ms Symonyan told them that Russia and China were victims of “information terrorism” by the Western media. She said the two countries must help each other because “we alone stand up to the mighty army of Western mainstream journalism.”

Mr Xi has been obliging. Russia’s Channel One—its main television channel, which has been whipping up anti-American fervour and support for Russia’s land-grab in Ukraine—has obtained permission to launch a cable service in China, called Katyusha, with subtitles in Chinese. Appropriately for the propaganda counter-attack that the two leaders see themselves as waging, Katyusha is the name of a Soviet rocket-launcher.

The breakdown of Russia’s relationship with the West as a result of the conflict in Ukraine has driven it further towards China. But the camaraderie masks fundamental differences. Russia needs China far more than China needs Russia. And Russia feels uncomfortable about such an unbalanced relationship that highlights a flaw in the Kremlin’s claim of Russian greatness. Russia is wary of its far more populous and economically potent neighbour, which is rapidly gaining in military power.

For its part, China worries about Russia’s willingness to challenge the post-cold war order. It has benefited from globalisation far more than Russia, and so is less inclined to disrupt the status quo.

Take China’s response to Russia’s intervention in Ukraine. Leaders in Beijing have turned a blind eye to it (just as Russia has to China’s seizing of disputed shoals in the South China Sea). But China has not formally recognised Russia’s annexation of Crimea. Chinese officials are fearful of how some people in China might interpret events there. After Crimea voted in a bogus referendum to join Russia, censors in China ordered media to play down the event. They did not want people in Taiwan, Tibet or the far western region of Xinjiang to think about determining their own future through such means. They also did not want Chinese nationalists to clamour for bolder moves to annex Taiwan.

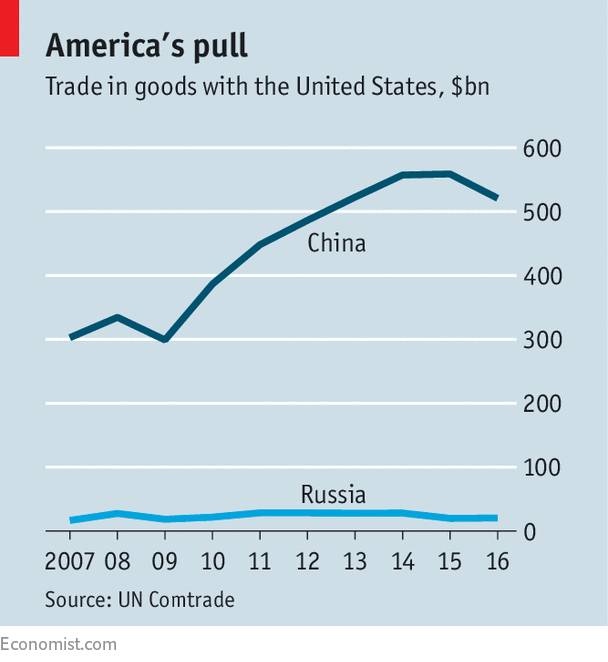

For China, economic ties with America, and therefore political ones, are hugely important. By comparison, Russian trade with America is negligible (see chart). In its trade with Russia, China is mostly interested in Russian oil and gas. Last year Russia overtook Angola and Saudi Arabia as the country’s biggest supplier of crude oil. In 2014 Russia and China signed a deal worth an estimated $400bn to pump natural gas to China from two fields in eastern Siberia via a new pipeline. The deliveries are set to start in December 2019. But negotiations over energy supplies are often bitter. Russia would like to divert to China oil and gas that is currently piped to Europe from western Siberia. But the two countries have not agreed on the funding of new pipelines that would be needed. Given the current low price of natural gas, China is reluctant to invest in building them.

The only other exports from Russia that matter to China are arms. Since the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, Russia has sold China $32bn worth of them, amounting to nearly 80% of all China’s arms imports. It has recently supplied China with advanced S-400 surface-to-air missile systems, and state-of-the-art Sukhoi SU-35 fighter jets. The Kremlin used to worry about China’s efforts to reverse-engineer them. But Alexander Gabuev of the Carnegie Moscow Centre says that Russia now recognises that China’s technological advance is unstoppable. Russia might as well make money from selling arms to China while China still has an interest in buying them from abroad rather than making them itself. Russia’s interests are mercenary rather than strategic: it also sells arms to China’s rivals, India and Vietnam.

The allure of silk

With Russia’s access to international capital markets now severed as a result of sanctions, China has become Russia’s main source of funds. Friends of Mr Putin, shunned by the West, are the main beneficiaries. One of them is Gennady Timchenko (“our man in China”, as Mr Putin describes him). Along with a son-in-law of Mr Putin, Mr Timchenko is a co-owner of Sibur, a petrochemical firm. In December 2015, Sibur sold 10% of its shares to Sinopec, China’s largest state-owned oil refinery, for $1.3bn. Last year Sibur sold another 10% of its shares to China’s state-backed Silk Road Fund, which invests in infrastructure.

As Chinese leaders see it, helping such people is a price worth paying in order to keep the supplies of energy and weapons flowing. But they see little prospect of Russia’s economy yielding any more than that. “For China, Russia matters first and foremost as a security issue, not as an economic one,” says a Chinese expert.

For that to change would require fundamental economic reform in Russia. Under Mr Putin, there is no prospect of that. Private investors in China shy away from Russia for the same reasons that their Western counterparts do: the lack of a robust legal system and clearly defined property rights. A senior Russian banker in China says a deep-rooted contempt for China in the Kremlin also gets in the way. “Russia’s biggest problem is that it does not know what it wants from this relationship. Our government wants Chinese money without the Chinese,” he says.

China has no illusions about Russian power. It sees it as weak and in decline. Successive American governments have reached the same conclusion. But whereas American leaders have tended to react by ignoring Russia, Chinese ones have done the opposite. They believe that an angry, declining power with nuclear arms requires more, not less, attention. Having watched Russia become a growing problem for the West, they do not want it to become a headache for China, too.

They know from history what a problem Russia can be for China. The “unbreakable friendship” between Russia and China that was declared by Stalin and Mao in 1950 nearly ended in a war between the two countries less than 20 years later. Fu Ying, a former Chinese diplomat who is now a legislator, remembers her fear as a teenager living close to China’s 4,200km (2,600-mile) border with Russia where hundreds of thousands of Soviet and Chinese troops faced off and the risk of war seemed very real. “The fact that we can be friends and no longer fear each other is significant in itself,” says Ms Fu.

Russia is also nervous of China. Despite this week’s war games in the Baltic Sea (and other joint ones in the past two years in the South China Sea and the Mediterranean), Russia stages exercises in preparation for a possible conflict with China. It fears that its densely populated neighbour may one day decide to grab sparsely populated lands in Russia’s east. Russian military planners are conscious of history: although China’s government is too polite to say so, ordinary Chinese recall that parts of that region, including Vladivostok, were China’s until the 19th century.

Ready to play with Russia

The two countries spar for influence in Central Asia, where China has become the leading trading partner for all the former Soviet republics (apart from Uzbekistan), as well as the region’s largest investor. Russia likes to think of itself as being the paramount military and political power in Central Asia, while China focuses on the economy. Yet as Bobo Lo, an Australian expert on the relationship, argues in a recent book, this arrangement is unsustainable. Mr Xi’s “Belt and Road Initiative”, aimed at linking China with Central Asia and countries beyond through infrastructure and energy projects, will give China much political clout in the region.

The asymmetry between Russia and China is particularly evident in Russia’s east. A few years ago residents there were spending their fast-rising incomes in China. But the rouble has become much weaker, and so has Russia’s economy. They now look to high-spending Chinese as their saviours. The numbers of such visitors are rapidly growing (though few venture there a second time). In Vladivostok, a travel agent says the city does not have enough decent rooms to accommodate them. On the streets, young Russians try to sell them old Soviet coins and banknotes.

Residents’ sense of shame at their country’s decline relative to China is palpable. In one hotel, Chinese visitors fill a stuffy restaurant where they watch scantily dressed dancers and women singing Russian folk songs. A performer walks out for some fresh air. Her face shows pain and humiliation. Chinese ships in the Baltic Sea (one is pictured), eight time zones away, will not make her feel any better.

——

Jul 27th 2017 | China | 1896 words