In the past, the most common way to

measure the safety performance of a business was to look at “lagging”

indicators. The number of incidents and injuries would be metrics

tasked with painting a comprehensive picture of the EHS performance of an organization, even if they entirely were based on historic data. Lagging indicators are easy to measure, but typically offer insight into the outcome of a process only after an incident has taken place. That means they’re rather tricky to influence.

Let’s think about our oldest of EHS friends: the numbers of incidents and injuries. They’re useful, sure, but only

to measure safety performance to date. Thus, they’re of extremely

limited use when attempting to improve future performance and prevent

further incidents from taking place.

Leading indicators can provide actionable EHS information

that can help reduce risk and encourage teams to be more proactive in

preventing incidents. You therefore can think of a leading indicator as

a form of predictive analysis. Predictive data can go one step

further than the “what” and “why” of an incident by giving an

indication as to what might happen next.

Research Into Leading Indicators

We recently worked with several companies on a leading indicator

initiative. Each of these companies is applying a common approach to

collect and analyze data from myriad risk-reduction activities such as

incident investigations, near-miss reports, management system audits,

risk assessments, assurance reviews, behavioral observations,

field-level inspection programs, hazard analysis and many other

processes. A recent analysis of a data set spanning 14 companies showed

an average of 58 sources of data totaling millions of records over

several years.

On the surface, each of these organizations simply have been using a

common “mechanism” to manage their own unique set of environmental,

health, safety and sustainability risk-reduction processes and

ultimately analyze the resulting data, i.e., the “outcome” (EHSS) data.

However, at a deeper level, these companies not only are

collecting data resulting from the outcomes (e.g., incident reports,

injury details, spill quantities, near-miss types, root causes, audit

results, assessment scores, inspection findings, etc.) but also the

work practice behaviors reflecting the organization’s tendencies in

executing such processes, such as the mean times between completion of

critical process steps, rate of leadership involvement in nonmandatory proactive steps, distribution of employee involvement in proactive activities and more.

With such a vast data set from both the outcomes and the work

practice behaviors, these companies created a unique opportunity not only

for themselves but also for anyone in the industry who is interested

in finding the real leading indicators of performance – those

activities, practices, factors, conditions, etc. – that are practically

measurable and are proven to have a mathematical relationship to loss outcomes.[DD1]

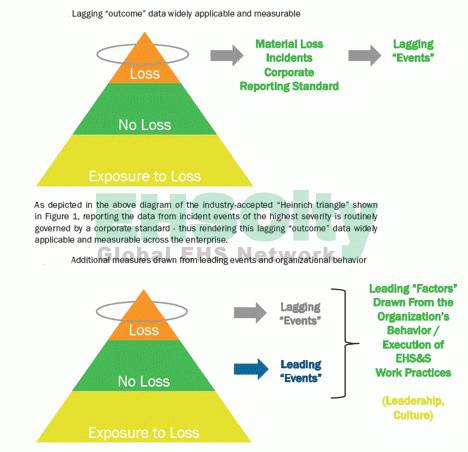

Drawing Leading Data from Lagging Events

It has become common to find companies that have implemented an enterprise-wide incident database

to collect data resulting from the outcomes of incidents. However,

some companies also are executing corporate-wide incident management

process improvement projects along with an information system that not only collects incident data, but also enables/facilitates each major step of the business process.

As depicted in Figure 1 below, applying a risk-reduction solution for

managing incident/near-miss events enables the full event life cycle –

from front-line worker reporting events to leadership involvement and

the remediation of action items – of the business process.

Sphera

Figure 1

By comprehensively facilitating the entire risk-reduction cycle

business process, the various levels of the workforce simply are

carrying out the routine incident/near-miss work practice using a

business process automation (BPA) tool. However, the byproduct of

facilitating each major step of all near-misses and incident events on

an integrated software platform is the ability to practically draw

measurements from both the incident/near-miss event outcome data and the

data reflecting the workers’ interaction with each step of those

business processes.

By analyzing the business process data to study the organizational

treatment of these lagging events, leading metrics such as the

percentage of the workforce involved in near-miss reporting, the ratio

of near-miss to high-consequence reports, the rate of leadership participating in nonmandatory events, consistency of manager response to key steps, and many other potential Leading Indicators of culture and leadership can be created.

Through this automation of lagging incident/near-miss business

processes, the data for calculating both lagging outcome metrics and

leading indicators is efficiently generated. The companies executing in

this manner are achieving the ironic accomplishment of drawing leading data values from the occurrence of lagging incident/near-miss events.

Sphera

Figure 2 and Figure 3

Integrating Key Work Steps

Most companies deploy a vast array of different proactive business

processes that fit the risk-reduction cycle pattern, ranging from formal

corporate-level auditing processes to more casual field-level

suggestion box/hazard ID type initiatives. Typically, the data resulting

from the outcomes of such proactive activities is scattered throughout

the organization on pieces of paper, spreadsheets, isolated databases and other nonintegrated systems, rendering broad measurements highly impractical.

An enterprise-wide risk-reduction solution enables the integration of

the key work practice steps and data elements across a wide array of

different proactive processes.

Per the previously mentioned average of 58 sources of

activities fitting this pattern, [DD2] roughly 90 percent of those

activities are proactive, assessment-based activities. By

facilitating a wide array of processes on a common BPA tool, the data

from both the outcomes of the activities and the work-practice

behaviors is available for trending across previously segregated

processes.

With this approach, common measurements can be drawn from processes,

which are routinely viewed as dissimilar. For example, the rate of

employee participation per a behavioral-based safety (BBS)

process can be combined with the rate of participation in other

dissimilar processes such as risk assessments, hazard ID reports,

inspections, self-assessments, walk-through audits and many others to

calculate a comprehensive rate of proactive employee involvement, a key

measure of reporting culture.

In addition, the final major step for all risk reduction cycle

activities entails the process of managing the action items required to

install protective controls and ultimately reduce the risk. With

efficient access to action item data from so many different processes,

the leading indicator metrics that can be drawn from action item

execution are broadly applicable and readily measurable as well.

The Key: Buy-in From Operational Management

Gaining the support of top management is in the critical path for

leading indicators to capture their fair share of this KPI landscape. In

a recent workshop conducted with leaders in environment,

health, safety and sustainability (EHSS) from several global operator

and service companies in the energy industry, the overwhelming choice

as the greatest obstacle to executing leading indicators was the

propensity of top leadership to use lagging metrics in annual

management performance objectives and in some cases as key components of manager incentive pay programs.

In today’s cost-competitive marketplace, budgets already are tight. Therefore, convincing operational

management to allocate the necessary resources for execution of the

programs that support a leading indicator initiative is met with

resistance rooted in skepticism. If you cannot convincingly demonstrate

that investing in such “leading” activities will result in better EHSS

performance, they won’t allocate the resources to execute such a

program. To overcome this obstacle, the most effective leading

indicators must meet the two following criteria:

1. Minimize additional resources required for execution.

2. Provide sufficient proof that executing leading indicators will improve EHSS performance.

Practical, usable, efficiently calculated metrics with a strong value

proposition are required to compel top leadership to give leading

indicators a prominent place on the KPI score cards of operational management.

The key components of leading indicators, which effectively may rival the practicality and importance of lagging metrics as KPIs to be executed on an enterprise scale are:

Simple, close connectivity to the outcome/results.

Objectively and reliably measurable.

Interpreted by different groups in the same way.

Broadly applicable across company operations.

Easily and accurately communicated.

Why do Lagging Metrics Still Dominate?

Many companies are tracking and analyzing leading indicators in

isolated areas of their businesses but few are applying leading

indicators to rival the age-old incident rate as the primary KPI for

judging an operation’s EHSS performance. One reason for this dominance

is the practicality of having a near standard in producing a

normalized performance metric, which can deliver an apples-to-apples

comparison of loss rates across the enterprise.

Whether a company uses a calculation similar to the OSHA standard or prefers the more internationally used denominator of 1 million exposure hours, the two key components

of safety loss rate measurement – the number of incidents and the

quantity of work hours – are much more broadly applicable and readily

measurable, thus rendering this type of lagging indicator a more

efficient and practical alternative.

In addition to the convenience of lagging indicators, how

many times have you heard: “It hasn’t happened here, so it is not a

problem”? Given both this human reactionary tendency and the convenience

of lagging metrics, leading indicators have quite a battle ahead if

they are to gain equal share of the KPI landscape for operations

management.

about the authors: Carrie Young is vice president of Consulting Services at Sphera, and is an expert in providing environmental and safety performance improvement through the development of integrated management systems, analytics, organizational

capability, enterprise software and governance. She has been helping

companies with business process transformation and insights for over 20

years. Todd Lunsford is director of Process Improvement at Sphera, and serves operational

excellence project advisor to Sphera customers, enabling them to make

critical decisions using the insights gained from their business

process data. Lunsford leads business process and usage assessments to

advance operational excellence maturity, drawing upon years of experience leading global deployments of operation risk solutions.

企业EHS咨询 请联系 [email protected]