Talking with a political opponent is almost as unpleasant as getting a tooth pulled.

If you ever thought, “You couldn’t pay me to listen to Sean Hannity / Rachael Maddow / insert any television pundit you violently disagree with here” — you are not alone.

A study, recently published in the Journal of Experimental and Social Psychology, essentially tested this very question.

Two hundred participants were presented with two options. They could either read and answer questions about an opinion they agreed with — the topic was same-sex marriage — or read the opposing viewpoint.

Here’s the catch: If the participants chose to read the opinion they agreed with, they were entered into a raffle pool to earn $7. If they selected to read opposing opinion, they had a chance to win $10.

You’d think everyone would want to win more money, right?

No.

A majority — 63 percent — of the participants chose to stick with what they already knew, forgoing the chance to win $10. Both people with pro same-sex marriage beliefs and those against it avoided the opinion hostile to their worldview at similar rates.

“They don’t know what’s going on the other side, and they don’t want to know,” Jeremy Frimer, the University of Winnipeg psychologist who led the study, says.

This is a key point that many people miss when discussing the “fake news” or “filter bubble” problem in our online media ecosystems. Avoiding facts inconvenient to our worldview isn’t just some passive, unconscious habit we engage in. We do it because we find these facts to be genuinely unpleasant. And as long as this experience remains unpleasant, and easy to avoid, we’re just going to drift further and further apart.

Listening to a political opponent is almost as bad as getting a tooth pulled

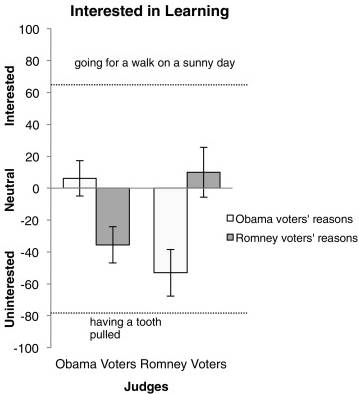

Frimer and his colleagues demonstrated this same effect with several different methodologies in their paper. In another test, they (essentially) asked participants to rate how interested they were in learning about alternative political viewpoints compared to activities like: “watching paint dry,” “sitting quietly,” “going for a walk on a sunny day,” and “having a tooth pulled.”

The results: Listening to a political opponent isn’t as awful as getting a tooth pulled, but it’s trending in that direction. It’s certainly a lot more awful than taking a leisurely stroll.

Obama voters were uninterested in learning about Romney voters’ political thinking. And vice versa.

Frimer also tested people’s knowledge of the opposing side. Largely, the partisans were unfamiliar with their viewpoints. So it’s not the case that people are avoiding learning about the other side because they’re already familiar. What’s going on here is “motivated ignorance,” as Matt Motyl, one of the study co-authors calls it.

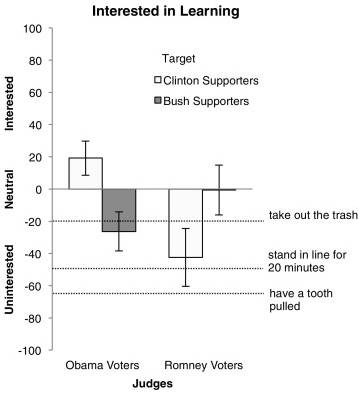

Frimer and colleagues also replicated this effect with Canadian samples in the 2015 national election there, and against Jeb Bush and Hillary Clinton supporters in the 2016 primaries. (Way back when they were both the frontrunners. Remember that? There’s often a long lag between the collection of scientific data and the publishing of a paper.) Democrats were about as interested in learning about Jeb Bush supporters’ motivations as they were interested in taking out trash.

“People on the left and right,” the study concludes, “are motivated to avoid hearing from the other side for some of the same reasons: the anticipation of cognitive dissonance and the undermining of a fundamental need for a shared reality with other people.”

Our need for a shared reality is the source of dysfunction in politics

This “fundamental need for a shared reality with other people” that Frimer and his colleagues describe all too often overshadows incentives to weigh evidence or to be objective when it comes to political discussions.

This is the dark truth that lies at the heart of all partisan politics, and makes me pessimistic that Facebook or any other social networking site can really solve the problem of people filtering into their own content bubbles. We automatically have an easier time remembering information that fits our worldviews. We’re simply quicker to recognize information that confirms what we already know, which makes us blind to facts that discount it. It’s the reason why that — paradoxically — as we learn more about politics and politically charged issues, we tend to become more rigid in our thinking.

“People are using their reason to be socially competent actors,” Dan Kahan, a psychologist at Yale, told me earlier this year. Put another way: We have a lot of pressure to live up to our groups’ expectations. And the smarter we are, the more we put our brain power to use for that end.

As long as people can curate what they see, and create their own content, there will be a small voice inside motivating us to stick with what we already know. We do this out of love for our in-groups. But also out of fear of the out-groups.

“We tend to view the other side as immoral, or evil, or crazy,” Motyl says. “And when we do that, it doesn’t make sense to say, ‘I want to understand immorality, or a crazy person’s perspective, or an ignorant perspective.” It’s too beyond the pale.

Why we’re unlikely to escape our filter bubbles

And this will continue to happen on both the left and right. A recent (not-yet-published) meta-analysis of 41 experimental studies on partisan bias found that liberals and conservatives “showed nearly identical levels of bias across studies.”

All the studies in the meta-analysis used the same basic design: Participants evaluated arguments for a cause, like gun control, that they were either predisposed to believe in or not. They were then asked to rate the quality of the evidence. Oftentimes, this evidence was completely made up. But whether you’re swayed by it or not — and the degree to which you agree with it — corresponds to your predispositions.

When it comes to these tasks, both liberals and conservatives failed to be critical.

“Together with a growing body of evidence suggesting that increased knowledge and expertise in a topic area exacerbates rather than ameliorates political bias, the prognosis for eradicating partisan bias with harder data and better education does not seem particularly rosy,” the meta-studies authors conclude.

(For people who might be thinking — “this is a false equivalence! How can you even compare the topics liberals are biased about to the topics conservatives are bias about!” — know that it is possible to be both biased and correct.)

Both liberals and conservatives fail here because the human brain fails here. The answer to “fake news” is not just deleting posts that are factually incorrect. It’s motivating people to be curious, and to seek out information that contradicts what they believe in an open-minded way.

Unless Facebook — or any social media — can find a means to make opposing points of view enjoyable to consume, or somehow incentivize seeing the other side, the internet will continue to divide and fracture into competing and alternative understandings of reality. Because right now the conclusion all this research points to is simple: We find interacting with other points of view to be unpleasant. And it’s hard to build a viral consumer product around an unpleasant experience.

There are a few theories on how to encourage people to listen to opposing views

Overall, psychologists are really good at diagnosing the problem of partisan thinking and partisan reasoning. Solutions to this problem are further afield. But Frimer says there are a few intriguing areas of research.

Often, in studies, if participants are warned that their responses need to be absolutely accurate, they won’t show confirmation bias as strongly. In a similar vein, there’s other new work that finds that stoking curiosity could be a means to break the cycle of partisan thinking. (And it could be that the price to get people to at least listen to the other side of an argument is higher than $3 extra.) The upshot: There may be ways to increase incentives for being accurate, or to target a person’s sense of curiosity to facilitate better political dialogue.

Overall, Motyl stresses that it’s wrong to think everyone disregards the other side in the same unified way. There’s nuance. Not all of us care about political issues equally. Not all of us are as attached to our political identities. Some personality traits, like agreeableness and openness, might make people better listeners.

But — on average — it’s an uphill battle. Because what we’re battling against is the tendencies of the human brain.

——

May 15, 2017 | 1413 words