China is a manufacturing juggernaut, an enormous force in global markets and, according to many in the Trump administration, a threat to U.S. technological and military supremacy.

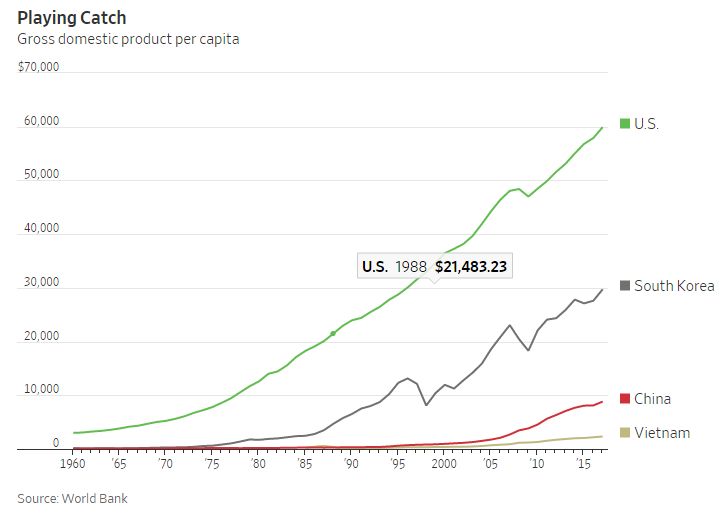

It is also, however, no longer as cheap as it once was. The country is beginning to bump up against income levels where some scholars believe nations are at higher risk of rapid growth slowdowns, as their cost advantage in cheap exports erodes but they fail to innovate rapidly enough in high-tech. China has legions of engineers and a rising weight in scientific publications, but it has still only produced a handful of global technology champions. Beijing’s answer is so-called “industrial upgrading” with the help of massive government capital. But state-led innovation has a checkered history in China, and the plan is sparking aggressive pushback from the U.S., which slapped new tariffs on China on Friday.

Only a handful of low and middle-income nations have managed to power into the high-income ranks since 1960—just 25 out of 156 as of 2016, according to Capital Economics. Whether China can buck those odds is probably the most important economic question of our time and will reshape the global investment environment.

A simple example illustrates the stakes. If China keeps growing around 6% a year and the U.S. keeps growing around 2%, 15 years from now China’s economy will be the largest in the world. If, however, China only grows at a compound annual rate of 4%, the U.S. economy will remain about a fifth larger. To be sure, that would still mean a massive Chinese economy. It also would mean a markedly poorer overall populace, upending growth plans of consumer-focused multinationals and making rising military expenditures more difficult. Any deterioration in the yuan’s value would widen the gap.

A worker welds a liquefied natural gas tank at a factory in Nantong in China's Jiangsu province.

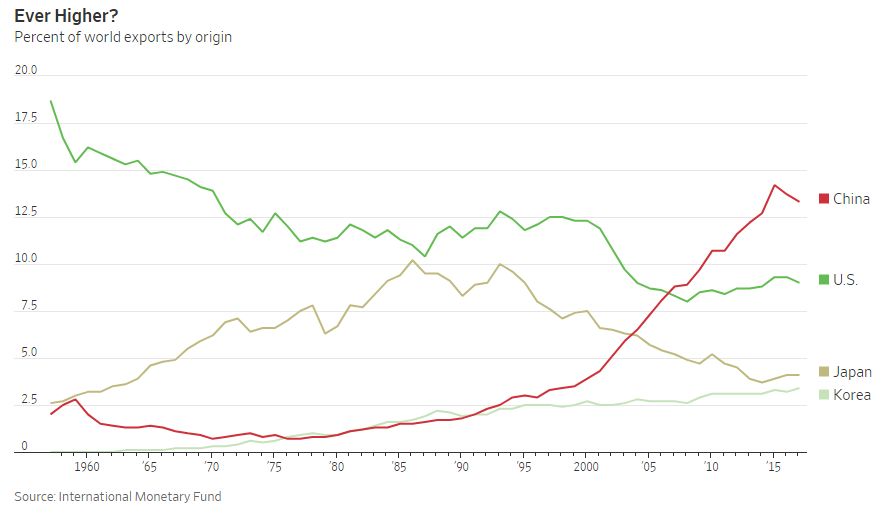

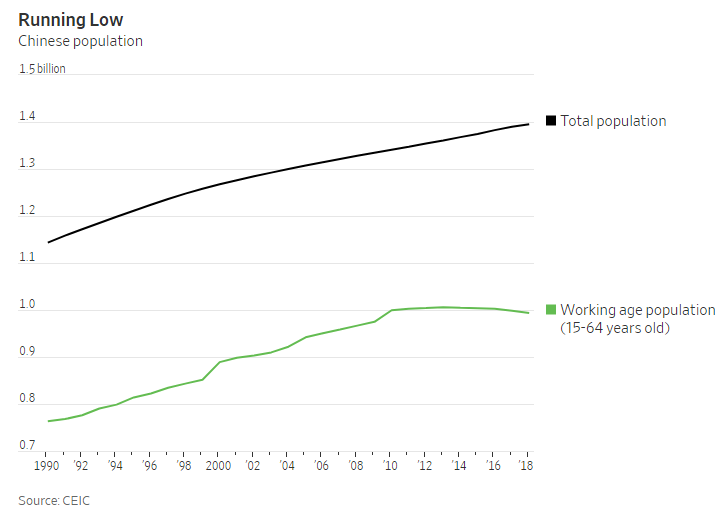

Despite its obvious advantages, several of the key factors driving China’s spectacular growth are moving into reverse. The total working-age population peaked in 2013, according to official figures. That means higher costs, and also slower growth in savings to finance investment, as a rapidly graying population stops saving for the future and starts spending. Meanwhile the nation’s export machine is already so large—13% of global shipments in 2017—that it is running into stiff political resistance abroad at much lower income levels than when trade tensions peaked for Japan in the 1980s. Continued rapid export growth, another key source of capital for investment, could prove difficult to sustain, even without competition from lower-cost aspirants like Vietnam.

Scarcer labor and savings ahead means that the big hope for keeping growth chugging along is boosting productivity and leveraging China’s massive internal market as a testing ground for new products, technologies and globally competitive champions.

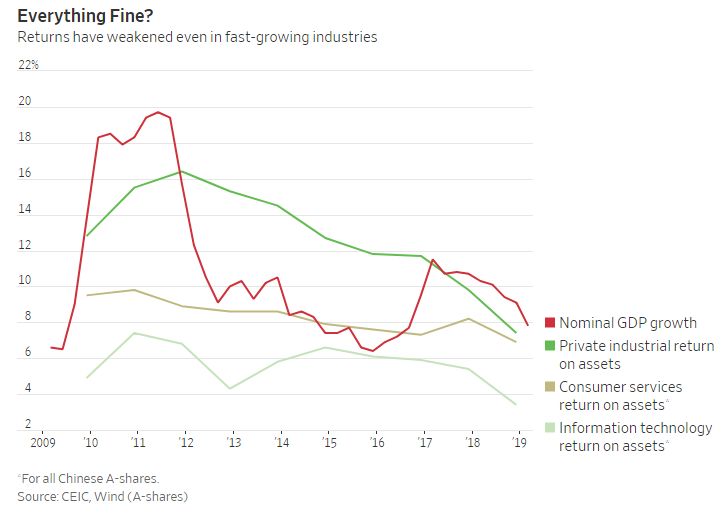

It isn’t clear, however, that Beijing is taking the steps needed to make this happen. Rather than bold new reforms, public policy in recent years has focused on shoring up the debt-addled state sector through industry consolidation—often at the expense of private competitors.

Return on assets for privately owned industrial companies, nearly 13% in 2014, was less than 8% last year. Even in the fast-growing information-technology sector, highfliers such as Tencent have found themselves facing tighter government scrutiny and subject to “mixed ownership reform,” encouraging them to invest large sums in ailing state giants. The state share of total investment, which declined steadily for most of the 2000s, has since 2012 stabilized at around 35%-40%.

A big internal market with ample state finance could indeed help build many new globally competitive innovators—but only if those financial resources find their way into good hands, and government interference doesn’t pose too much of a problem for winners. In today’s China, this seems more, not less, questionable than a few years ago.

A 2018 analysis from Capital Economics finds that, while in most countries large firms tend to have higher return on assets than smaller firms due to economies of scale, in China the reverse is true for both private and state-owned companies. One explanation could be that many small private manufacturers in China are part of international export supply chains and therefore directly exposed to global market discipline, unlike large, domestically focused companies.

Other explanations are more disturbing. Even successful Chinese companies like Tencent are exposed to a high level of government interference once they reach scale. That weighs on returns. Or the companies that grow to scale may do so primarily because of political connections and cheap finance, rather than quality per se. Either way, the conclusion isn’t encouraging.

What is encouraging are subtle signs in recent months that Beijing realizes that the past year in particular has been very rough for entrepreneurs. Large banks are being ordered to lend more to small companies, substantial business tax cuts have been rolled out and official rhetoric on lowering private-sector costs has hardened. None of this is the same as big-bang reforms like full interest rate liberalization or opening more state-controlled sectors to domestic and foreign competition, but it is a step in the right direction.

Ironically, China’s best hope to keep growing rapidly might be a trade deal featuring exactly the sort of competition-boosting reforms the Trump administration is asking for—a fairer, wider playing field for private capital and toothier intellectual-property enforcement. That would also help preserve Chinese access to Western markets and technical expertise. Chinese nationalists may disagree. In the long run, though, a deal forcing real change might help, not hinder the Chinese rejuvenation the current leadership proselytizes.

——

May 14th 2019 | 925 words