译者按:William Deresiewicz,美国《国家》杂志撰稿人、《新共和》杂志编辑

What Are You Going to Do With That?

你要过什么样的生活?

By William Deresiewicz

William Deresiewicz

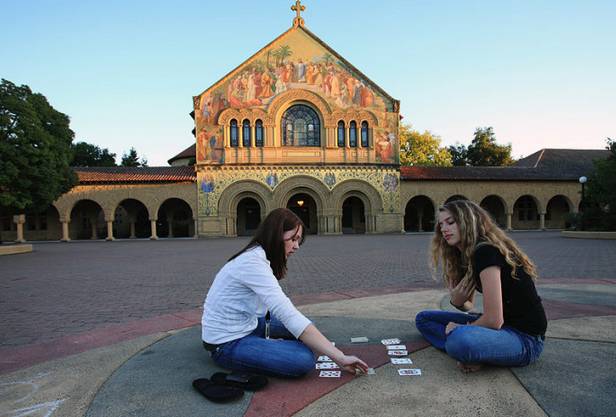

The essay below is adapted from a talk delivered to a freshman class at Stanford University in May.

根据在斯坦福大学5月份时的报告改编。

The question my title poses, of course, is the one that is classically aimed at humanities majors. What practical value could there possibly be in studying literature or art or philosophy? So you must be wondering why I'm bothering to raise it here, at Stanford, this renowned citadel of science and technology. What doubt can there be that the world will offer you many opportunities to use your degree?

我的题目提出的问题,当然,是一个经典的面向人文科学的专业所提出的问题:学习文学、艺术或哲学能有什么实效价值?你肯定纳闷,我为什么在以科技闻名的斯坦福提出这个问题呢?大学学位当然是给人们带来众多的机会,这还有什么需要质疑的吗?

But that's not the question I'm asking. By "do" I don't mean a job, and by "that" I don't mean your major. We are more than our jobs, and education is more than a major. Education is more than college, more even than the totality of your formal schooling, from kindergarten through graduate school. By "What are you going to do," I mean, what kind of life are you going to lead? And by "that," I mean everything in your training, formal and informal, that has brought you to be sitting here today, and everything you're going to be doing for the rest of the time that you're in school.

但那不是我提出的问题。这里的“做”并不是指工作,“那”也不是指你的专业。我们的价值不仅仅是我们的工作,教育的意义也不仅仅是让你学会你的专业。教育的意义大于是上大学的意义,甚至大于你从幼儿园到研究生院的所接受的所有正规学校教育的意义。我说的“你要做什么”的意思是你要过什么样的生活?我所说的“那”指的是你得到的正规或非正规的任何训练,那些把你送到这里来的东西,你在学校的剩余时间里将要做的任何事。

We should start by talking about how you did, in fact, get here. You got here by getting very good at a certain set of skills. Your parents pushed you to excel from the time you were very young. They sent you to good schools, where the encouragement of your teachers and the example of your peers helped push you even harder. Your natural aptitudes were nurtured so that, in addition to excelling in all your subjects, you developed a number of specific interests that you cultivated with particular vigor. You did extracurricular activities, went to afterschool programs, took private lessons. You spent summers doing advanced courses at a local college or attending skill-specific camps and workshops. You worked hard, you paid attention, and you tried your very best. And so you got very good at math, or piano, or lacrosse, or, indeed, several things at once.

我们不妨先来讨论你是如何考入斯坦福的吧。你能进入这所大学说明你在某些技能上非常出色。你的父母在你很小的时候就鼓励你追求卓越。他们送你到好学校,老师的鼓励和同伴的榜样作用激励你更努力地学习。除了在所有课程上都出类拔萃之外,你还注重修养的提高,充满热情地培养了一些特殊兴趣。你参加了许多课外活动,参加私人课程。你用几个暑假在本地大学里预习大学课程,或参加专门技能的夏令营或训练营。你学习刻苦、精力集中、全力以赴。所以,你可能在数学、钢琴、曲棍球等方面都很出色,甚至是个全能选手。

Now there's nothing wrong with mastering skills, with wanting to do your best and to be the best. What's wrong is what the system leaves out: which is to say, everything else. I don't mean that by choosing to excel in math, say, you are failing to develop your verbal abilities to their fullest extent, or that in addition to focusing on geology, you should also focus on political science, or that while you're learning the piano, you should also be working on the flute. It is the nature of specialization, after all, to be specialized. No, the problem with specialization is that it narrows your attention to the point where all you know about and all you want to know about, and, indeed, all you can know about, is your specialty.

掌握这些技能当然没有错,全力以赴成为最优秀的人也没有错。错误之处在于这个体系遗漏的地方:即任何别的东西。我并不是说因为选择钻研数学,你在充分发展话语表达能力的潜力方面就失败了;也不是说除了集中精力学习地质学之外,你还应该研究政治学;也不是说你在学习钢琴时还应该学吹笛子。毕竟,专业化的本质就是要专业性。可是,专业化的问题在于它把你的注意力限制在一个点上,你所已知的和你想探知的东西都限界于此。真的,你知道的一切就只是你的专业了。

The problem with specialization is that it makes you into a specialist. It cuts you off, not only from everything else in the world, but also from everything else in yourself. And of course, as college freshmen, your specialization is only just beginning. In the journey toward the success that you all hope to achieve, you have completed, by getting into Stanford, only the first of many legs. Three more years of college, three or four or five years of law school or medical school or a Ph.D. program, then residencies or postdocs or years as a junior associate. In short, an ever-narrowing funnel of specialization. You go from being a political-science major to being a lawyer to being a corporate attorney to being a corporate attorney focusing on taxation issues in the consumer-products industry. You go from being a biochemistry major to being a doctor to being a cardiologist to being a cardiac surgeon who performs heart-valve replacements.

专业化的问题是它只能让你成为专家,切断你与世界上其他任何东西的联系,不仅如此,还切断你与自身其他潜能的联系。当然,作为大一新生,你的专业才刚刚开始。在你走向所渴望的成功之路的过程中,进入斯坦福是你踏上的众多阶梯中的一个。再读三年大学,三五年法学院或医学院或研究型博士,然后再干若干年住院实习生或博士后或者助理教授。总而言之,进入越来越狭窄的专业化轨道。你可能从政治学专业的学生变成了律师或者公司代理人,再变成专门研究消费品领域的税收问题的公司代理人。你从生物化学专业的学生变成了博士,再变成心脏病学家,再变成专门做心脏瓣膜移植的心脏病医生。

Again, there's nothing wrong with being those things. It's just that, as you get deeper and deeper into the funnel, into the tunnel, it becomes increasingly difficult to remember who you once were. You start to wonder what happened to that person who played piano and lacrosse and sat around with her friends having intense conversations about life and politics and all the things she was learning in her classes. The 19-year-old who could do so many things, and was interested in so many things, has become a 40-year-old who thinks about only one thing. That's why older people are so boring. "Hey, my dad's a smart guy, but all he talks about is money and livers."

我再强调一下,你这么做当然没有什么错。只不过,在你越来越深入地进入这个轨道后,再想回忆你最初的样子就越发困难了。你开始怀念那个曾经谈钢琴和打曲棍球的人,思考那个曾经和朋友热烈讨论人生和政治以及在课堂内容的人在做什么。那个活泼能干的19岁年轻人已经变成了只想一件事的40岁中年人。难怪年长的人总是显得那么乏味无趣。“哎,我爸爸曾经是非常聪明的人,但他现在除了谈论钱和肝脏外再无其他。”

And there's another problem. Maybe you never really wanted to be a cardiac surgeon in the first place. It just kind of happened. It's easy, the way the system works, to simply go with the flow. I don't mean the work is easy, but the choices are easy. Or rather, the choices sort of make themselves. You go to a place like Stanford because that's what smart kids do. You go to medical school because it's prestigious. You specialize in cardiology because it's lucrative. You do the things that reap the rewards, that make your parents proud, and your teachers pleased, and your friends impressed. From the time you started high school and maybe even junior high, your whole goal was to get into the best college you could, and so now you naturally think about your life in terms of "getting into" whatever's next. "Getting into" is validation; "getting into" is victory. Stanford, then Johns Hopkins medical school, then a residency at the University of San Francisco, and so forth. Or Michigan Law School, or Goldman Sachs, or Mc Kinsey, or whatever. You take it one step at a time, and the next step always seems to be inevitable.

还有另外一个问题,就是或许你从来就没有想过当心脏病医生,只是碰巧发生了而已。随大流最容易,这就是体制的力量。我不是说这个工作容易,而是说做出这种选择很容易。或者,这些根本就不是自己做出的选择。你来到斯坦福这样的名牌大学是因为聪明的孩子都这样。你考入医学院是因为它的地位高,人人都羡慕。你选择心脏病学是因为当心脏病医生的待遇很好。你做那些事能给你带来好处,让你的父母感到骄傲,令你的老师感到高兴,也让朋友们羡慕。从你上高中开始,甚至初中开始,你的唯一目标就是进入最好的大学,所以现在你会很自然地从“如何进入下个阶段”的角度看待人生。“进入”就是能力的证明,“进入”就是胜利。先进入斯坦福,然后是约翰霍普金斯医学院,再进入旧金山大学做实习医生等。或者进入密歇根法学院,或高盛集团或麦肯锡公司或别的什么地方。你迈出了这一步,似乎就必然会迈出下一步。

Or maybe you did always want to be a cardiac surgeon. You dreamed about it from the time you were 10 years old, even though you had no idea what it really meant, and you stayed on course for the entire time you were in school. You refused to be enticed from your path by that great experience you had in AP history, or that trip you took to Costa Rica the summer after your junior year in college, or that terrific feeling you got taking care of kids when you did your rotation in pediatrics during your fourth year in medical school.

也许你可能确实想当心脏病学家。十岁时就梦想成为医生,即使你根本不知道医生意味着什么。你在上学期间全身心都在朝着这个目标前进。你拒绝了上大学预修历史课的美妙体验的诱惑,也无视你在医学院第四年儿科病床轮流值班时照看孩子的可怕感受。

But either way, either because you went with the flow or because you set your course very early, you wake up one day, maybe 20 years later, and you wonder what happened: how you got there, what it all means. Not what it means in the "big picture," whatever that is, but what it means to you. Why you're doing it, what it's all for. It sounds like a cliché, this "waking up one day," but it's called having a midlife crisis, and it happens to people all the time.

但不管是那种情况,要么因为你使随大流,要么因为你早就选定了道路,20年后某天你醒来,你可能会纳闷到底发生了什么:你是怎么变成了现在这个样子,这一切意味着什么。不是说在宽泛意义的事情,而是它对你意味着什么。 你为什么做它,到底为了什么呢。这听起来像老生常谈,但这个被称为中年危机的“有一天醒来”的情况一直就发生在每个人身上。

There is an alternative, however, and it may be one that hasn't occurred to you. Let me try to explain it by telling you a story about one of your peers, and the alternative that hadn't occurred to her. A couple of years ago, I participated in a panel discussion at Harvard that dealt with some of these same matters, and afterward I was contacted by one of the students who had come to the event, a young woman who was writing her senior thesis about Harvard itself, how it instills in its students what she called self-efficacy, the sense that you can do anything you want. Self-efficacy, or, in more familiar terms, self-esteem. There are some kids, she said, who get an A on a test and say, "I got it because it was easy." And there are other kids, the kind with self-efficacy or self-esteem, who get an A on a test and say, "I got it because I'm smart."

不过,还有另外一种情况,或许中年危机并不会发生在你身上。让我告诉你们一个你们的同龄人的故事来解释我的意思吧,即她是没有遇到中年危机的。几年前,我在哈佛参加了一次小组讨论会,谈到这些问题。后来参加这次讨论的一个学生给我联系,这个哈佛学生正在写有关哈佛的毕业论文,讨论哈佛是如何给学生灌输她所说的“自我效能”,一种相信自己能做一切的意识。自我效能或更熟悉的说法“自我尊重”。她说在考试中得了优秀的学生中,有些会说“我得优秀是因为试题很简单。”但另外一些学生,那种具有自我效能感或自我尊重的学生,会说“我得优秀是因为我聪明。”

Again, there's nothing wrong with thinking that you got an A because you're smart. But what that Harvard student didn't realize—and it was really quite a shock to her when I suggested it—is that there is a third alternative. True self-esteem, I proposed, means not caring whether you get an A in the first place. True self-esteem means recognizing, despite everything that your upbringing has trained you to believe about yourself, that the grades you get—and the awards, and the test scores, and the trophies, and the acceptance letters—are not what defines who you are.

我得再次强调,认为得了优秀是因为自己聪明的想法并没有任何错。不过,哈佛学生没有认识到的是他们没有第三种选择。当我指出这一点时,她十分震惊。我指出,真正的自尊意味着最初根本就不在乎成绩是否优秀。真正的自尊意味着,尽管你在成长过程中的一切都在教导你要相信自己,但你所达到的成绩,还有那些奖励、成绩、奖品、录取通知书等所有这一切,都不能来定义你是谁。

She also claimed, this young woman, that Harvard students take their sense of self-efficacy out into the world and become, as she put it, "innovative." But when I asked her what she meant by innovative, the only example she could come up with was "being CEO of a Fortune 500." That's not innovative, I told her, that's just successful, and successful according to a very narrow definition of success. True innovation means using your imagination, exercising the capacity to envision new possibilities.

她还说,哈佛学生把他们的这种自我效能带到了社会上,并将自我效能重新命名为“创新”。但当我问她“创新”意味着什么时,她能够想到的唯一例子不过是“当上世界大公司五百强的首席执行官”。我告诉她这不是创新,这只是成功,而且是根据非常狭隘的成功定义而认定的成功而已。真正的创新意味着运用你的想象力,发挥你的潜力,创造新的可能性。

But I'm not here to talk about technological innovation, I'm here to talk about a different kind. It's not about inventing a new machine or a new drug. It's about inventing your own life. Not following a path, but making your own path. The kind of imagination I'm talking about is moral imagination. "Moral" meaning not right or wrong, but having to do with making choices. Moral imagination means the capacity to envision new ways to live your life.

但在这里我并不是想谈论技术创新,不是发明新机器或者制造一种新药,我谈论的是另外一种创新,是创造你自己的生活。不是走现成的道路而是创造一条属于自己的道路。我谈论的想象力是道德想象力。“道德”在这里与对错无关,而与选择有关。道德想象力是那种能创造新的活法的能力。

It means not just going with the flow. It means not just "getting into" whatever school or program comes next. It means figuring out what you want for yourself, not what your parents want, or your peers want, or your school wants, or your society wants. Originating your own values. Thinking your way toward your own definition of success. Not simply accepting the life that you've been handed. Not simply accepting the choices you've been handed. When you walk into Starbucks, you're offered a choice among a latte and a macchiato and an espresso and a few other things, but you can also make another choice. You can turn around and walk out. When you walk into college, you are offered a choice among law and medicine and investment banking and consulting and a few other things, but again, you can also do something else, something that no one has thought of before.

它意味着不随波逐流,不是下一步要“进入”什么名牌大学或研究生院。而是要弄清楚自己到底想要什么,而不是父母、同伴、学校、或社会想要什么。即确认你自己的价值观,思考迈向自己所定义的成功的道路,而不仅仅是接受别人给你的生活,不仅仅是接受别人给你的选择。当今走进星巴克咖啡馆,服务员可能让你在牛奶咖啡、加糖咖啡、浓缩咖啡等几样东西之间做出选择。但你可以做出另外的选择,你可以转身而去。当你进入大学,人家给你众多选择,或法律或医学或投资银行和咨询以及其他,但你同样也可以做其他事,做从前根本没有人想过的事。

Let me give you another counterexample. I wrote an essay a couple of years ago that touched on some of these same points. I said, among other things, that kids at places like Yale or Stanford tend to play it safe and go for the conventional rewards. And one of the most common criticisms I got went like this: What about Teach for America? Lots of kids from elite colleges go and do TFA after they graduate, so therefore I was wrong. TFA, TFA—I heard that over and over again. And Teach for America is undoubtedly a very good thing. But to cite TFA in response to my argument is precisely to miss the point, and to miss it in a way that actually confirms what I'm saying. The problem with TFA—or rather, the problem with the way that TFA has become incorporated into the system—is that it's just become another thing to get into.

让我再举一个不随波逐流的例子。几年前我写过一篇涉及同类问题的文章。我说,那些在耶鲁和斯坦福这类名校的孩子往往比较随大溜,去追求一些传统职业。(译者:比如去投行,高级律师事务所等等)我得到的最常见的批评是:那些名校的孩子不都去参加“为美国而教”这个教育项目了吗?从名校出来的很多学生毕业后很多参与这个教育项目,因此我的观点是错误的。TFA,TFA我一再听到这个术语。“为美国而教”当然是好东西,但引用这个项目来反驳我的观点恰恰是不对的,而且实际上正好证明了我想说的东西。“为美国而教”的问题或者“为美国而教”已经成为体系一部分的问题,是它已经成为另外一个需要“进入”的门槛。

In terms of its content, Teach for America is completely different from Goldman Sachs or McKinsey or Harvard Medical School or Berkeley Law, but in terms of its place within the structure of elite expectations, of elite choices, it is exactly the same. It's prestigious, it's hard to get into, it's something that you and your parents can brag about, it looks good on your résumé, and most important, it represents a clearly marked path. You don't have to make it up yourself, you don't have to do anything but apply and do the work —just like college or law school or McKinsey or whatever. It's the Stanford or Harvard of social engagement. It's another hurdle, another badge. It requires aptitude and diligence, but it does not require a single ounce of moral imagination.

从其内容来看,“为美国而教”完全不同于高盛或者麦肯锡公司或哈佛医学院或者伯克利法学院,但从它在精英期待的体系中的地位来说,完全是一样的。它享有盛名,很难进入,是值得你和父母夸耀的东西,如果写在简历上会很好看,最重要的是,它代表了清晰标记的道路。你根本不用自己创造,什么都不用做,只需申请然后按要求做就行了,就像上大学或法学院或麦肯锡公司或别的什么。它是社会参与方面的斯坦福或哈佛,是另一个门槛,另一枚奖章。该项目需要能力和勤奋,但不需要一丁点儿的道德想象力。

Moral imagination is hard, and it's hard in a completely different way than the hard things you're used to doing. And not only that, it's not enough. If you're going to invent your own life, if you're going to be truly autonomous, you also need courage: moral courage. The courage to act on your values in the face of what everyone's going to say and do to try to make you change your mind. Because they're not going to like it. Morally courageous individuals tend to make the people around them very uncomfortable. They don't fit in with everybody else's ideas about the way the world is supposed to work, and still worse, they make them feel insecure about the choices that they themselves have made—or failed to make. People don't mind being in prison as long as no one else is free. But stage a jailbreak, and everybody else freaks out.

道德想象力是困难的,这种困难与你已经习惯的困难完全不同。不仅如此,光有道德想象力还不够。如果你要创造自己的生活,如果你想成为真正的独立思想者,你还需要勇气:道德勇气。不管别人说什么,有按自己的价值观行动的勇气,不会因为别人不喜欢而试图改变自己的想法。具有道德勇气的个人往往让周围的人感到不舒服。他们和其他人对世界的看法格格不入,更糟糕的是,让别人对自己已经做出的选择感到不安全或无法做出选择。只要别人也不享受自由,人们就不在乎自己被关进监狱。可一旦有人越狱,其他人都会跟着跑出去。

In A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, James Joyce has Stephen Dedalus famously say, about growing up in Ireland in the late 19th century, "When the soul of a man is born in this country there are nets flung at it to hold it back from flight. You talk to me of nationality, language, religion. I shall try to fly by those nets."