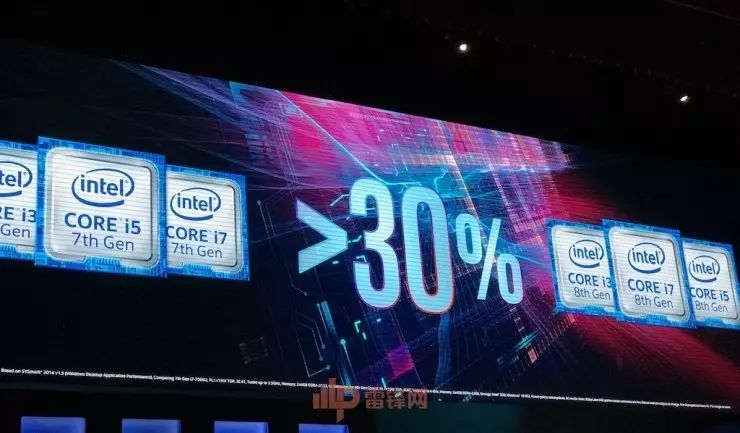

网络社会中物质不是稀缺的,信息也不是稀缺的,而是注意力是稀缺的。注意力的稀缺性导致了它可以转化为财富。当今社会,对“注意力”的讨论早已司空见惯,但是当我们将注意力视为一种资源,从商业和心理学的角度去利用它时,我们谈论的“注意力”,究竟是什么?

看!

作者:Tom Chatfield

翻译:朱星汉&泮海伦

笔记导读&推荐阅读:沈园园

策划:王瑞

The attention economy

注意力经济

本文选自

Aeon

| 取经号原创翻译

关注 取经号,

回复关键词“外刊”

获取《经济学人》等原版外刊获得方法

How many other things are you doing right now while you’re reading this piece? Are you also checking your email, glancing at your Twitter feed, and updating your Facebook page? What five years ago David Foster Wallace labelled ‘Total Noise’ — ‘the seething static of every particular thing and experience, and one’s total freedom of infinite choice about what to choose to attend to’ — is today just part of the texture of living on a planet that will, by next year, boast one mobile phone for each of its seven billion inhabitants. We are all

amateur

attention economists,

hoarding

and

bartering

our moments — or watching them slip away down the cracks of a thousand YouTube clips.

当你在读这篇文章的时候,是否在看邮件,刷推特,刷脸书?手头还干着其他的事情?五年前,大卫•福斯特•华莱士提出了“无处不在的噪声”——“无穷无尽的事件和体验占据着我们的生活,而我们可以随心所欲地决定自己要留意哪些”——现在,这种环境不过是我们日常生活的一种写照,毕竟,明年世界将会有超过70亿的手机持有者。在分配注意力时,我们都算得上是

业余

经济学家,我们

贮藏

自己的时间或用时间

交换

其他东西,要么就在观看YouTube视频时不知不觉消费掉它们。

译注:注意力经济(Attention Economy)是一种管理信息的方法,它将人类的注意力作为一种稀缺的资源并且运用经济学理论解决各种各样的信息管理问题。马修•克劳福德(Matthew Crawford)的解释则为“注意力是一种资源 - 且每个人都是有限的”。 同时人类能够把注意力集中在处理的信息上的能力有限,即注意力有限。形成一种类似经济学的有限资源与无限欲望的对价关系,甚至比实际货币的影响更宏大,关系到该企业或个人的收益成败,所以称为注意力经济。

大卫•佛斯特•华莱士,美国小说家,1962年2月21日出生于美国纽约州伊萨卡。其在文学上极富有造诣,与乔纳森•弗兰茨并称为美国当代文学“双璧”。内容上,他一直以巨大的好奇心关注这个物质的世界,以及生活在这个世界的人们的感受,尤其是那些生活在20世纪末的美国的人们。在作品广受赞誉同时,他也饱受抑郁症折磨,年仅四十六岁便在家中自杀身亡。

If you’re using a free online service, the

adage

goes, you are the product. It’s an

arresting

line, but one that deserves putting more precisely: it’s not you, but your behavioural data and the quantifiable facts of your engagement that are constantly blended for sale, with the aggregate of every single interaction (yours included) becoming a mechanism for ever-more-finely tuning the business of attracting and retaining users.

常言

道:你在使用免费的在线服务时,“就已经成为了产品本身”。这句话很

耐人寻味

,但确切来说,应该是:“真正被出售的不是你,而是你的行为所产生的数据,以及你使用记录下的所有可量化信息。为了更精确、更好地吸引并留住用户,来自每个人的数据(包括你的)都被整合到了一起,专业利用”。

adage

/

'ædɪdʒ/

n traditional saying; proverb 格言; 箴言; 谚语.

arresting

/

ə'rest

ɪ

ŋ

/adj attracting attention; striking 引人注意的

Consider the confessional slide show released in December 2012 by Upworthy, the ‘website for viral content’, which detailed the mechanics of its online attention-seeking. To be truly viral, they note, content needs to make people want to click on it and share it with others who will also click and share. This means selecting stuff with instant appeal — and then precisely calibrating the summary text, headline, excerpt, image and tweet that will spread it. This in turn means producing at least 25 different versions of your material, testing the best ones, and being prepared to constantly

tweak

every aspect of your site. To play the odds, you also need to publish content constantly, in quantity, to maximise the likelihood of a hit — while keeping one eye glued to Facebook. That’s how Upworthy got its most viral hit ever, under the headline ‘Bully Calls News Anchor Fat, News Anchor Destroys Him On Live TV’, with more than 800,000 Facebook likes and 11 million views on YouTube.

具有病毒式传播速度的网站Upworthy于2012年12月公布的ppt详细坦白了它是如何抓住网民眼球的:要真正走红,内容需要引起人们点击与分享的欲望,并且接受分享的对象也会继续传播给下一个人。这意味着选择一些能带来即时热度的内容,随后准确地调整简介、标题、摘录、图像以及推特输入框中的内容,使其符合大范围传播的要求。同时至少需要为材料制备25种不同的版本,把最好的一些推送出去,并准备随时

微调

网站的方方面面。为了增加蹿红几率,发布内容要及时,数量也要多——还需紧盯脸书上的新闻热点。凭此一招,Upworthy制作出了史无前例的头条新闻——《被观众嫌胖,女主播公开回呛》,在Facebook上获80万赞,在YouTube上有1100万次观看量。

tweak

/ twiːk / vt. If you tweak something such as a system or a design, you improve it by making a slight change. 稍稍改进(如系统或设计)

译注:Upworthy 是有史以来发展速度最快的网站之一。但它只制作极少量的原创材料。Upworthy 选取人们上传到网上的视频,重新包装后重磅推出。

But even Upworthy’s efforts pale into insignificance compared with the algorithmic might of sites such as Yahoo! — which, according to the American author and marketer Ryan Holiday, tests more than 45,000 combinations of headlines and images every five minutes on its home page. Much as corporations incrementally improve the taste, texture and sheer

enticement

of food and drink by measuring how hard it is to stop eating and drinking them, the actions of every individual online are fed back into measures where more inexorably means better: more readers, more viewers, more exposure, more influence, more ads, more opportunities to unfurl the integrated apparatus of gathering and selling data.

然而,强大如Upworthy,也在雅虎这样拥有强大算法的网站前败下阵来。美国作家、营销人员赖恩·霍利迪称雅虎每5分钟就会对45000组标题图像的组合进行测试。正如一些公司通过对抵制美食诱惑的难易程度进行测试来不断改进食品及饮料的口味、质感以及纯粹的

诱惑

力,互联网上每个人的行为都会被反馈成测评信息,传播量越大自然越好:阅读量越高、播放量越大、曝光率越高、影响力越大、广告越多,就有更多机会对数据进行收集和贩卖。

enticement

/

ɪ

nˈta

ɪ

smənt/ N-VAR An enticement is something that makes people want to do a particular thing. 诱惑物

Attention, thus conceived, is an inert and finite resource, like oil or gold: a tradable asset that the wise manipulator auctions off to the highest bidder, or speculates upon to lucrative effect. There has even been talk of the world reaching ‘peak attention’, by analogy to peak oil production, meaning the moment at which there is no more spare attention left to spend.

因此,注意力被视为一种惰性及有限的资源,就像石油和黄金,是一种可交易的资产,明智的操控者能把它拍卖给出最高价的买家,或者直接利用它干投机买卖,获取利益。类比石油峰值,甚至有了“关注峰值“这样的说法,意思是在特定的时间点,某事件的关注度达到顶峰的情况。

This is one way of conceiving of our time. But it’s also a quantification that tramples across other, qualitative questions — a fact that the American author Michael H Goldhaber recognised some years ago, in a piece for Wired magazine called ‘Attention Shoppers!’ (1997). Attention, he argued, ‘comes in many forms: love, recognition, heeding, obedience, thoughtfulness, caring, praising, watching over, attending to one’s desires, aiding, advising, critical appraisal, assistance in developing new skills, et cetera. An army sergeant ordering troops doesn’t want the kind of attention Madonna seeks. And neither desires the sort I do as I write this.’

虽然这仅仅是理解时间的一种方式,但这种从量化来理解时间的角度,相比起其他要给时间定性的角度,要高明的多。美国作家迈克尔·高尔德哈伯于1997年在《连线》杂志上刊登的《注意力购买者》一文提到:“注意力以多种形式存在:爱、认可、注意、遵从、深思、关怀、赞美、照看、关照某人的欲求、援助、建议、给予批判性评价、培训等。一位军士在给下属下达命令后,他想要得到的回应绝不会是麦当娜期望从观众那里得到的回应,这两种回应也不是我在写这篇文章时心里所期望的。”

译注:据资料显示,迈克尔·高尔德哈伯早在1989年就已开始研究注意力经济。他在1997年1月哈佛大学肯尼迪政治学院组织的“数字信息经济”会议上发表的《注意力经济与网络》(《The attention economy and the net 》)已提出“注意力经济”这一概念。但当时他的研究对象并不限于传媒经济的范围,而是针对整个社会经济。就其论述来看,主要是针对旧经济(工业经济)与新经济(网络社会/信息社会的经济)的不同之处,以及信息社会的特点去阐述注意力经济的。迈克尔·高尔德哈伯的《注意力经济与网络》和《注意力的售卖》两文章,基本观点都差不多,主要指出:

1、 网络/信息社会中物质不是稀缺的,信息也不是稀缺的,而是注意力是稀缺的。

2、 注意力的稀缺性导致了它可以转化为财富。

3、 注意力比货币更加重要。注意力是第一位的,货币是第二位的。

4、注意力经济最需要的是创新。

5、负面的注意力也比没有注意力好。

For all the sophistication of a world in which most of our waking hours are spent consuming or interacting with media, we have scarcely advanced in our understanding of what attention means. What are we actually talking about when we base both business and mental models on a ‘resource’ that, to all intents and purposes, is fabricated from scratch every time a new way of measuring it comes along?

尽管世界如此复杂难解,我们却把醒着的大多数时间花在了社交媒体上,而对注意力这个词的理解则迟迟停滞不前。在我们每次以新的角度去审视注意力的时候,实际上这个概念就重新被定义了。那么,在我们将注意力视为一种资源,从商业和心理学的角度去利用它时,我们谈论的“注意力”,究竟是什么?

Attending is closely connected to anticipation. Soldiers snap to attention to signify readiness and respect — and to embody it. Unable to read each others’ minds, we demand outward shows of mental engagement. Teachers shout ‘Pay attention!’ at slumped students whose thoughts have meandered, calling them back to the place they’re in. Time, presence and physical attentiveness are our most basic

proxies

for something ultimately unprovable: that we are understood.

“注意力”这个词与“期望”紧密联系。士兵立正象征着准备就绪与尊敬,也代表着他们正全神贯注。我们没有读心术,要知道他人的内心活动只能观察他人的行为。老师对走神的学生说:“注意了!”,把他们的思维拉回到教室里。时间、存在和身体上表现出的专注这第三者构成了最基本的衡量我们是否被他人理解的指标,但这种衡量

指标

却并不可靠。

The best teachers, one hopes, don’t shout at their students — because they are skilled at wooing as well as demanding the best efforts of others. For the ancient Greeks and Romans, this wooing was a sufficiently fine art in itself to be the central focus of education. As the manual on classical rhetoric Rhetorica ad Herennium put it 2,100 years ago: ‘We wish to have our hearer receptive, well-disposed, and attentive (docilem, benivolum, attentum).’ To be civilised was to speak persuasively about the things that mattered: law and custom, loyalty and justice.

人们总是希望良师不对学生大声斥责,因为他们善于赢得学生的爱戴,并激发学生的斗志。对古希腊人和古罗马人来说,赢得学生爱戴是教育艺术的核心。2100前的修辞学经典著作《Rhetorica ad Herennium》的指导中写到:“我们希望自己的听众善于听取意见,能够接受我们的看法,保持全神贯注。”有涵养之士谈及法律、习俗、忠诚和正义等重要议题时应循循善诱。

This vision of puppeteers effortlessly pulling everyone else’s strings — however much it might fulfil both geek fantasies and Luddite nightmares — is distinctly dubious

看起来像是木偶师在毫不费力地操纵着作为木偶的我们,虽然多多少少能够迎合极客们的幻想,让反对科技进步的群体更加恐慌,但这种看法却站不住脚。

Underpinning this was neither honour nor idealism, but

pragmatism

embodied in a five-part process. Come up with a compelling proposition, arrange its elements in elegant sequence, polish your style, commit the result to memory or media, then pitch your delivery for maximum impact. Short of an ancient ‘share’ button, the similarities to Upworthy’s recipe for going viral are impressive. Cicero, to whom Rhetorica ad Herennium is traditionally attributed, also counted

flattery

, bribery, favour-bargaining and outright untruth among the tools of his trade. What mattered was results.

支撑这句话的既不是荣誉,也不是理想主义,而是体现为“五部曲”的

实用主义

。提出一个吸人眼球的命题,考究地排列一下要素,打磨你的话语风格,将最终结果付诸存储器或媒介,将其投放出去,使产生的影响最大化。在没有“分享”键的古代,用类似Upworthy的传播方案引发病毒式传播,可谓出神入化。西塞罗是《Rhetorica ad Herennium》一书世人公认的作者,他也将

奉承

、贿赂、投其所好、弄虚作假视为传播工具。毕竟,传播效果好才是最终目的。

flattery

/ ˈflætər

ɪ

/ [U] Flattery consists of flattering words or behaviour. 奉承(表不满)

However, when it comes to automated systems for garnering attention, there’s more at play than one person listening to another; and the processes of measurement and persuasion have some uncannily totalising tendencies. As far as getting the world to pay attention to me online, either I play by the rules of the system — likes, links, comments, clicks, shares, retweets — or I become ineligible for any of its glittering prizes. As the American writer and software engineer David Auerbach put it in n+1 magazine, in a piece pointedly titled ‘The Stupidity of Computers’ (2012), what is on screen demands nothing so much as my complicity in its assumptions: