繁忙都市中可以不和自己多年的左邻右舍说一句话,对

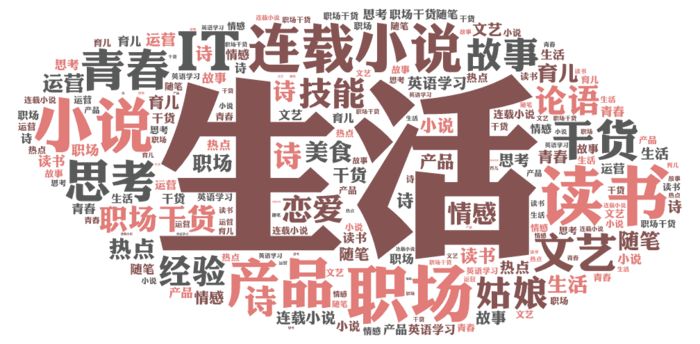

整个世界都充满了不信任感的现代人越来越感到孤独,却愿意在社交媒体和广播电台中感受生活,书写生活,或长篇大论,或三言两语,我们借此展露自己,似乎大千世界就只剩下一隅偏安的自嗨,我们越急于用文字表达自己,就越无法理解世界,表达心事,甚至会失去更多可能性。我们生来是自由的,但这种自由不是建立在能言善辩的基础之上,单单依靠话语,不论你怀揣着多么强烈的表现欲望,世界也绝不会成为你的话筒!

膨胀的表达欲,渺小的你我他

作者:

Tom Chatfield

译者:张鑫健&朱星汉

校对:朱星汉&朱小钊

导读&笔记:泮海伦&朱小钊

策划: 朱星汉&朱小钊

I type, therefore I am

我写故我在

本文选自

AEON

| 取经号原创翻译

关注 取经号,

回复关键词“外刊”

获取《经济学人》等原版外刊获得方法

More human beings can write and type their every thought than ever before. Something to celebrate or deplore?

能写字、能打字的人比以前多了很多,这到底是好事还是坏事?

At some point in the past two million years, give or take half a million, the genus of great apes that would become modern humans crossed a unique threshold. Across unknowable reaches of time, they developed a communication system able to describe not only the world, but the inner lives of its speakers. They ascended — or fell, depending on your preferred metaphor — into language.

在过去二百万年间的某个时间点(前后五十万年),类人猿跨越了一个特殊的节点,即将进化成智人。不知过了多久,这群类人猿进化出了一套交流系统,不仅能描述外部世界,还能表达内心感受。就这样,它们进入——或有些人更喜欢说,陷入了——语言的世界里。

The vast bulk of that story is silence. Indeed, darkness and silence are the defining norms of human history. The earliest known writing probably emerged in southern Mesopotamia around 5,000 years ago but, for most of recorded history, reading and writing remained among the most elite human activities: the province of monarchs, priests and nobles who reserved for themselves the privilege of lasting words.

寂静是进化的主题。诚然,黑暗与寂静是人类历史的基调。已知最早的手写文字纪录可以追溯到约5000年前的美索不达米亚南部,但纵观史书,阅读和写作在大部分时间都是核心的精英阶层才能进行的活动,只有帝王、牧师和贵族的小圈子才享有用文字记录的特权。

Mass literacy is a phenomenon of the past few centuries, and one that has reached the majority of the world’s adult population only within the past 75 years. In 1950, UNESCO estimated that 44 per cent of the people in the world aged 15 and over were illiterate; by 2012, that proportion had reduced to just 16 per cent, despite the trebling of the global population between those dates. However, while the full effects of this revolution continue to

unfold

, we find ourselves in the throes of another whose statistics are still more accelerated.

大部分民众能识字的现象是近几个世纪内才出现的,在过去的75年中,全世界绝大多数成年人才能识字。1950年,据联合国教科文组织估计,在全世界所有15岁以上的人中,文盲率高达44%;而在2012年,这一数字下降至16%,而且世界人口在此期间增长了两倍。随着扫盲运动逐步

展开

,另一波运动正愈演愈烈,同时伴随着数字的疯狂增长。

In the past few decades, more than six billion mobile phones and two billion internet-connected computers have come into the world. As a result of this, for the first time ever we live not only in an era of mass literacy, but also — thanks to the act of typing onto screens — in one of mass participation in written culture.

在过去几十年内,全世界新增逾六十亿部智能手机,逾二十亿台接入互联网的电脑,人类首次迈入“万众识字”的时代,同时由于电子设备的输入功能,人类也第一次浸淫在了“万众写字”的文化中。

As a medium, electronic screens possess infinite capacities and instant interconnections, turning words into a new kind of active agent in the world. The 21st century is a truly hypertextual arena (hyper from ancient Greek meaning ‘over, beyond, overmuch, above measure’). Digital words are interconnected by active links, as they never have and never could be on the physical page. They are, however, also above measure in their supply, their distribution, and in the stories that they tell.

作为一种媒介,电子设备容量极大,即时互联,它让文字变得更加鲜活。21世纪是超文本(Hypertextual,其中hyper词源为古希腊,意为“高于、超过、过多的、难以估量的”)的舞台。数字时代的文本通过链接相互联系,因为它们不可能,也未曾全部打印出来。它们是取之不尽、用之不竭的,它们所传递的信息也是难以估量的。

Just look at the ways in which most of us, every day, use computers, mobile phones, websites, email and social networks. Vast volumes of mixed media surround us, from music to games and videos. Yet almost all of our online actions still begin and end with writing: text messages, status updates, typed search queries, comments and responses, screens packed with verbal exchanges and,

underpin

ning it all, countless billions of words.

我们大多数人都使用电脑和手机浏览网站,登录社交平台,收发邮件,可谓生活在琳琅满目的媒体设备中,从音乐到游戏到视频一应俱全。然而我们在互联网上的绝大多数活动仍是以打字开始,又以打字结束:发送消息、更新状态、输入搜索框、发表评论,满屏幕都是文字交互。这一切的

背后是

无穷尽的文字。

Underpin

/ˌʌndəˈpɪn / v. to support or form the basis of an argument, a claim, etc. 加强,巩固,构成(…的基础等)

This sheer quantity is in itself something new. All future histories of modern language will be written from a position of explicit and overwhelming information — a story not of darkness and silence but of data, and of the verbal outpourings of billions of lives. Where once words were written by the literate few on behalf of the many, now every phone and computer user is an author of some kind. And — separated from human voices — the tasks to which typed language, or visual language, is being put are steadily multiplying.

这庞大的量级本身便是前所未有的。在未来,现代语言历史的出发点是不再是黑暗与寂静的故事,而是清晰而巨量的信息,是数十亿人制造的浩如烟海的文字信息。曾经,只有少数文化人才能使用文字,他们就代表了其他人;而现在,每一位手机、电脑用户在某种意义上都是独立的作者。而除了声音以外,人类所录入的文字,或称视觉语言,所承载的任务量也与日俱增。

Consider the story of one of the information age’s minor icons, the

emoticon

. In 1982, at Carnegie Mellon University, a group of researchers were using an online bulletin board to discuss the hypothetical fate of a drop of mercury left on the floor of an elevator if its cable snapped. The scenario prompted a humorous response from one participant — ‘WARNING! Because of a recent physics experiment, the leftmost elevator has been contaminated with mercury. There is also some slight fire damage’ — followed by a note from someone else that, to a casual reader who hadn’t been following the thread, this comment might seem alarming (‘yelling fire in a crowded theatre is bad news… so are jokes on day-old comments’).

以当今信息时代最简单的

表情符号

为例,它背后的故事是这样的:1982年,卡耐基梅伦大学有一群研究人员在BBS上探讨了这样一个问题:如果一个电梯的线缆断裂了,而电梯地面上恰好有一滴水银,那么这滴水银将会如何?这场讨论中产生了一则幽默的评论:警告!最左侧电梯因近期物理实验而受到水银污染,其中可能还有些因火灾导致的轻微损坏。随后有人回复这则评论道,如果读者并未完整读完这篇帖子,他可能会觉得这条评论带有警告意味(‘在拥挤的剧院中,有人大喊火灾肯定是坏事…互联网早期的评论里也是这样’)。

Participants thus began to suggest symbols that could be added to a post intended as a joke, ranging from per cent signs to ampersands and hashtags. The clear winner came from the computer scientist Scott Fahlman, who proposed a smiley face drawn with three punctuation marks to denote a joke :-). Fahlman also typed a matching sad face :-( to suggest seriousness, accompanied by the prophetic note that ‘it is probably more economical to mark things that are NOT jokes, given current trends’.

因此,这些讨论者纷纷建议可以在发表的内容里加入某种符号,代表这些文字具有的玩笑意味。有人建议用“%”,还有人建议用“&”和“#”,但一位名为斯科特·法尔曼的计算机科学家毫无悬念的获胜了,他用三个标点符号设计出了笑脸符号(:-)),用它来表达开玩笑的意味;同时他还设计了配套的哭泣符号(:-(),用来暗示严肃意味。同时,他还预言:“鉴于当下情况,这可能是表达某事绝非玩笑的最省时省力的办法了。”

Within months, dozens of smiley variants were creeping across the early internet: a kind of proto-virality that has led some to label emoticons the ‘first online meme’. What Fahlman and his colleagues had also

enshrined

was a central fact of online communication: in an interactive medium, consequences rebound and multiply in unforeseen ways, while miscommunication will often become the rule rather than the exception.

数月之内,大批笑脸符号的变体版本迅速席卷了当时的互联网:它是最原始的互联网病毒式传播,因此也有人将其称为“初代表情包”。法尔曼和他的同事也

强调

了网上交流的核心概念:在互动式媒体中,某种结果会以各种难以预计的方式传播、放大,而错误信息也通常会根深蒂固,而不是烟消雾散。

enshrine

[ɪnˈʃraɪn]v.to contain or keep as if in a holy place 把…奉为神圣;珍藏

Three decades later, we’re faced with the logical conclusion of this trend: an appeal at the High Court in London last year against the conviction of a man for a ‘message of menacing character’ on Twitter. In January 2010, Paul Chambers, 28, had tweeted his frustration at the closure of an airport near Doncaster due to snow: ‘Crap! Robin Hood Airport is closed. You’ve got a week and a bit to get your shit together, otherwise I’m blowing the airport sky high!!’

三十多年后,我们终于看到了表情符号可能会引发的后果:2012年,一男子因在推特上发表“带有恐吓字眼的信息”而遭到指控,而有人将此事上诉给伦敦高院。在2010年1月份,唐卡斯特一家机场因大雪关停,28岁的保罗· 钱伯斯在推特上发牢骚称:“我X,罗宾汉机场关了。你们就剩一周多一点的时间来收拾好自己的破烂滚蛋走人了,否则我就把这地方炸个稀巴烂!”

Chambers had said he never thought anyone would take his ‘silly joke’ seriously. And in his judgment on the ‘Twitter joke trial’, the Lord Chief Justice said that — despite the omission of a smiley emoticon — the tweet in question did not constitute a credible threat: ‘although it purports to address “you”, meaning those responsible for the airport, it was not sent to anyone at the airport or anyone responsible for airport security… the language and punctuation are inconsistent with the writer intending it to be or to be taken as a serious warning’.

钱伯斯称,他从没想过真的会有人把自己“弱智的玩笑话”当真。首席法官对这起“推特玩笑案”的判决意见是——尽管本案中的推文并没有使用笑脸符号,但也并未构成实在的威胁:“尽管推文中提到的‘你们’指机场的负责人员,但这条推文并没有发送给机场工作人员,也没有发送给机场安保人员……用词和标点说明作者并不带有恐吓意图,也不希望别人把它当成一则正经的警告。”

The phrase a ‘victory for common sense’ was widely used by supporters of the charged man, such as the comedians Stephen Fry and Al Murray. As the judge also noted, Twitter itself represents ‘no more and no less than conversation without speech’: an interaction as spontaneous and

layer

ed with contingent meanings as face-to-face communication, but possessing the permanence of writing and the reach of broadcasting.

支持钱伯斯无罪的人(比如喜剧演员斯蒂芬·弗雷和阿尔·穆雷)中流行这样一个短语:“常识的胜利。”法官同时指出,推特代表了一种“无声的对话”:它和面对面交谈一样,

充满

即兴因素,话语含义也因当时情况而定;但同时,它又具备写作的永续性,以及和广播相媲美的传播范围。

layer

/ˈleɪə(r) / v. to arrange sth in layers 把…分层堆放

It’s an observation that speaks to a central contemporary fact. Our screens are in increasingly direct competition with spoken words themselves — and with traditional conceptions of our relationship with language. Who would have thought, 30 years ago, that a text message of 160 characters or fewer, sent between mobile phones, would become one of the defining communications technologies of the early 21st century; or that one of its natural successors would be a tweet some 20 characters shorter?

这样的论断与当代某种核心观点十分接近。互联网时代的文字与我们的口头表达的交锋越来越直接,它与传统观念里人类和语言之间关系的交锋也越来越直接。30年前,有谁能想到不足160字的、在手机间传递信息的短信会成为21世纪早期最主要的沟通手段呢?谁又会想到,不足20字的推特会取代短信呢?

Yet this bare textual minimum has proved to be the perfect match to an age of information suffusion: a manageable space that conceals as much as it reveals. Small wonder that the average American teenager now sends and receives around 3,000 text messages a month — or that, as the MIT professor Sherry Turkle reports in her book Alone Together (2011), crafting the perfect kind of

flirtatious

message is so serious a skill that some teens will outsource it to the most eloquent of their peers.

然而,这种极其短小的文字体量却和这个信息臃肿的时代完美契合,文字长度可控,既有所表达,也有所保留。难怪每个普通美国少年每月都要收发3000条短消息,也难怪麻省理工学院教授雪莉·特克尔在她2011年出版的书籍《群体性孤独》中写道:要写出完美的

勾搭

短信是一项很正式的技能,有些小伙子甚至会把这项工作外包给最老道的同龄人。

Almost without our noticing, we weave worlds from these snapshots, until an illusion of unbroken narrative emerges.

几乎在不知不觉之中,我们从零散的几张快照拼凑出他人的生活,最后,我们陷入了从只言片语间读取完整故事的错觉中。

It’s not just texting, of course. In Asia, so-called ‘chat apps’ are re-enacting many millions of times each day the kind of exchanges that began on bulletin boards in the 1980s, complete not only with animated emoticons but with integrated access to games, online marketplaces, and even video calls. Phone calls, though, are a degree of self-exposure too much for most everyday communications. According to the article ‘On the Death of the Phone Call’ by Clive Thompson, published in Wired magazine in 2010, ‘the average number of mobile phone calls we make is dropping every year… And our calls are getting shorter: in 2005 they averaged three minutes in length; now they’re almost half that.’ Safe behind our screens, we let type do our talking for us — and leave others to

conjure

our lives by reading between the lines.

当然不只是短信如此,在亚洲,所谓的“聊天软件”每天都在不断重现上世纪80年代BBS的信息交流方式。这种改变绝不仅仅是靠会动的表情包完成的,更是由于软件内整合了游戏、购物甚至视频电话等功能。而在日常通信中,相比起其他沟通手段,打电话就显得有些过分“袒露”自我了。克莱夫·汤姆森2010年在《连线》杂志上发表了文章《论电话通信的死亡》,他在文中写道:“我们平均每天拨打电话的数量在逐年减少……每次的通话时长也在缩短:2005年,平均通话时长为3分钟,现在通话时长几乎少了一半。”我们安全地躲在屏幕背后,任由打字取代讲话的任务——寄希望于他人能从字里行间拼凑出我们的生活。

Conjure

/ˈkʌndʒə(r) / v. to do clever tricks such as making things seem to appear or disappear as if by magic 变魔术;变戏法;使…变戏法般地出现(或消失)

Yet written communication doesn’t necessarily mean safer communication. All interactions, be they spoken or written, are to some degree performative: a negotiation of roles and references. Onscreen words are a special species of self-presentation — a form of storytelling in which the very idea of ‘us’ is a fiction crafted letter by letter. Such are our linguistic gifts that a few sentences can conjure the story of a life: a status update, an email, a few text messages. Almost without our noticing, we weave worlds from these snapshots, until an illusion of unbroken narrative emerges from a handful of paragraphs.

但文字通信并不代表安全程度更高。所有互动行为,不管是口头的还是书面的,都带有表演性质,都是角色与说法的交流。屏幕上的文字是特殊的自我呈现——在这种叙事模式下,“我们”这一概念是逐字虚构出来的。我们的语言天赋让我们能从只言片语中脑补出他人生活,不管是状态更新、邮件还是几封短消息。几乎在不知不觉之中,我们从零散的几张快照拼凑出他人的生活,最后,我们陷入了从只言片语间读取完整故事的幻觉。

Behind this illusion

lurk

s another layer of belief: that we can control these second selves. Yet, ironically, control is one of the first things our eloquence sacrifices. As authors and politicians have long known, the afterlife of our words belongs to the world — and what it chooses to make of them has little to do with our own assumptions.

在这一幻觉背后

潜藏

的观念是,我们能掌握自己的第二个自我(即网络化的自我)。但讽刺的是,我们巧言善辩的代价首先就是失去对第二自我的控制。作家和政治家们早就明白,我们留下的文字的在我们死后将属于这个世界,而世界会怎样看待这些文字,不是我们能预料到的。

lurk

/lɜːk / v. when sth unpleasant or dangerous lurks, it is present but not in an obvious way (不好或危险的事)潜在,隐藏着

In many ways, mass articulacy is a crisis of originality. Something always implicit has become ever more starkly explicit: that words and ideas do not belong only to us, but play out without larger currents of human feeling. There is no such thing as a private language. We speak in order to be heard, we write in order to be read. But words also speak through us and, sometimes, are as much a dissolution as an assertion of our identity.

从很多方面来看,当人人都得以表达的时候,语言的独创性便会式微。一个一直以来比较隐晦的真相现在昭然若揭了:话语和想法并不是我们的所有物,它们不是人类情感作用的结果。私人语言并不存在,我们说话是希望有人能听到,书写是希望有人会阅读。但我们同时也是话语的载体,甚至有些时候,话语在不断强化我们身份的同时也在消解我们的身份。

译注:维特根斯坦在《哲学研究》第243节里设想了一种私人语言(private language):“这种语言的语词指涉只有讲话人能够知道的东西;指涉他的直接的、私有的感觉。因此另一个人无法理解这种语言。”

In his essay ‘Writing: or, the Pattern Between People’ (1932), W H Auden touched on the paradoxical relationship between the flow of written words and their ability to satisfy those using them:

在《写作:或人与人之间的模式》(1932)一文中,威斯坦·休·奥登提到,作者笔下的文字并不能满足其本身的写作欲望。

Since the underlying reason for writing is to bridge the gulf between one person and another, as the sense of loneliness increases, more and more books are written by more and more people, most of them with little or no talent. Forests are cut down, rivers of ink absorbed, but the

lust

to write is still unsatisfied.

写作在根本上是为了减少人与人之间的隔阂。随着孤独感的增强,越来越多人开始写书,但大多数人要么没有写作的天赋,要么天赋平平。消耗了大量的木材和墨水,但他们写作的

欲望

却依然没有得到满足。

Lust

/lʌst / n. very strong desire for sth or enjoyment of sth 强烈欲望;享受欲

Onscreen, today’s torrents of

pixels

exceed anything Auden could have imagined. Yet the hyper-verbal loneliness he evoked feels peculiarly contemporary. Increasingly, we interweave our actions and our rolling digital accounts of ourselves: curators and narrators of our life stories, with a matching move from internal to external monologue. It’s a realm of elaborate shows in which status is hugely significant — and one in which articulacy itself risks turning into a game, with attention and impact (retweets, likes) held up as the supreme virtues of self-expression.

今天,高清的电子设备远超奥登的想象,但他所提到的因孤独而写作欲旺盛的现象却特别贴近当下,我们开始在社交媒体上表现自我,自己讲述自己的故事,滔滔不绝,吐露内心世界。社交媒体是一个自我展现的绝佳平台,在其中占有一席之地至关重要。同时,在社交媒体上表达自己也变成了提高关注度和影响力(转发和点赞)的一种手段,自我表达最大的好处便是会赢得关注度和影响力。

Pixel

/ˈpɪksl / n. any of the small individual areas on a computer screen, which together form the whole display 像素(组成屏幕图像的最小独立元素)

Consider the particular phenomenon known as binary or ‘reversible language’ that now proliferates online. It might sound obscure, but the pairings it entails are central to most modern metrics of measured attention, influence and interconnection: to ‘like’ and to ‘unlike’, to ‘favourite’ and to ‘unfavourite’; to ‘follow’ and ‘unfollow’; to ‘friend’ and ‘unfriend’; or simply to ‘click’ or ‘unclick’ the onscreen boxes enabling all of the above.

想想“二进制”语言或“二分法”语言这一特殊的现象,这在互联网上特别常见。虽然这个术语听起来比较晦涩,但是它所包含的两方面含义对于如何以当代视角来理解关注、影响、互动等可量化的行为至关重要。比如,“喜欢”还是“讨厌”;“最喜欢的”还是“最讨厌的”;“关注”还是“不关注”;“好友”还是“陌生人”。亦或是“点击”还是“不点击”以上这些内容的按钮。

Like the systems of organisation underpinning it, such language promises a clean and quantifiable recasting of self-expression and relationships. At every stage, both you and your audience have precise access to a measure of reception: the number of likes a link has received, the number of followers endorsing a tweeter, the items ticked or unticked to populate your profile with a galaxy of preferences.

就像其背后的组织系统一样(互联网建立在二进制的基础上),二进制式的语言以一种清晰、可量化的方式重塑了自我表达以及人与人之间的关系。在所有的舞台上,你和观众都可以精准地获得反馈,比如,点赞的数量、推文的关注人数以及根据个人喜好勾选的个性清单等。

译注:社会学家欧文·戈夫曼在其符号互动理论中用“表演”一词来指代个体持续面对特定观察者时所表现的、并对那些观察者产生了某些影响的全部行为,“舞台”则是进行表演活动的场所

What’s on offer is a kind of perpetual present, in which everything can always be exactly the way you want it to be (provided you feel one of two ways). Everything can be undone instantly and effortlessly, then done again at will, while the machinery itself can be shut down,

logged off

or ignored. Like the author oscillating between Ctrl-Y (redo) and Ctrl-Z (undo) on a keyboard, a hundred indecisions, visions and revisions are permitted — if desired — and all will remain unseen. There is no need, ever, for any conversation to end.

眼前所见就像是无休止的进行时,一切都可以呈现你想要的样子。你可以毫不费力地立刻按下撤销然后重做,也可以关掉电脑、

退出

系统或是将电脑弃于一旁。就像我自己经常在撤销和反撤销之间按来按去,即使你有一百次犹豫不决,一百个构想,或是一百次修订(如果你确定要这么做的话),都不是大问题,因为其他人是看不到的。所有的对话,其实都没有必要停止了。

Log off

to finish using a computer system (从计算机系统)退出;注销

Even the most ephemeral online act leaves its mark. Data only accumulates. Little that is online is ever forgotten or erased, while the business of search and social recommendation funnels our words into a perpetual popularity contest. Every act of selection and interconnection is another reinforcement. If you can’t find something online, it’s often because you lack the right words. And there’s a deliciously circular logic to all this, whereby what’s ‘right’ means only what displays the best search results — just as what you yourself are ‘like’ is defined by the boxes you’ve ticked. It’s a grand game with the most glittering prizes of all at stake: connection, recognition, self-expression, discovery. The internet’s countless servers and services are the perfect riposte to history: an eternally unfinished collaboration, pooling the words of many millions; a final refuge from darkness.

即便是一次短暂的访问也会留下痕迹,数据只增不减,只有极少部分的数据被永久删除了。搜索引擎和社交媒体上的推荐将我们的言论推入永不停歇的人气竞赛,每一次选择(二分法语言)和互动,都会使这场竞赛更加激烈。如果你在互联网上查不到某件东西,八成是因为你没有输入正确的字,这里就存在一个值得玩味的循环逻辑,即“正确”意味着只显示最佳搜索结果,就像你喜欢的东西都是由你自己勾选的。互联网是一场巨型赌局,看你能否赢得最终大奖,即人脉、认同感、自我表达和新鲜事物。互联网拥有无数的服务器和设备,人类可以永远保持合作,千言万语汇集于此,人类终于在黑暗中找到了最终的庇佑,互联网是对历史的完美诠释。

There’s much to celebrate in this

profligate

democracy, and its overthrow of articulate monopolies. The self-dramatising ingenuity behind even three letters such as ‘LOL’ is a testament to our capacity for making the most constricted verbal arenas our own, while to watch events unfold through the fractal lens of social media is a unique contemporary privilege. Ours is the first epoch of the articulate crowd, the smart mob: of words and deeds fused into ceaseless feedback.

值得高兴的是,信息时代虽然带来了一种“

过度

参与”的民主,却终结了少数群体垄断知识的时代。我们甚至能在“LOL(laughing out loud)”这样三个字母的简写中找到通过戏剧化手段表达自我的智慧灵光,“LOL”充分证明了我们能够驾驭最严谨的文字,此外,通过社交媒体的碎片化视角来观察事件也是当今时代的人们得天独厚的优势。这是我们第一次进入一个属于普罗大众皆可表达自我的时代,一个同样属于聪明暴民的时代,行为和言论共同作用,便诞生了源源不断的反馈信息。

Profligate

/ˈprɒflɪgət / adj. using money, time, materials, etc. in a careless way 挥霍的;浪费的

Yet language is a

bewitchment

that can overturn itself — and can, like all our creations, convince us there is nothing beyond it. In an era when the gulf between words and world has never been easier to overlook, it’s essential to keep alive a sense of ourselves as distinct from the cascade of self-expression; to push back against the torrents of articulacy flowing past and through us.

但语言的

魔力

可能会反噬自身,也有可能像人类其他的发明一样,让我们相信这便是最伟大的创造。当今时代,语言与世界的边界十分模糊,因此,我们必须保持清醒的意识,不再沉溺于自我表达,抗击这股即将吞噬我们乃至所有人的浪潮。

For the philosopher John Gray, writing in The Silence of Animals (2013), the struggle with words and meanings is sometimes simply a distraction: