Humans have excellent olfaction and can smell more than a trillion odors.

Humans are the superior animal on planet Earth. We have huge brains that allow us to build skyscrapers and come up with dazzling inventions like pizza and the internet. We’re highly visual, with the ability to pick out the face of a friend in a crowd and paint realistic works of art with our hands and eyes alone.

But we’ve long believed these strengths came at a cost: our sense of smell.

“People are sometimes taught that because humans developed such a good visual system, we lost a sense of smell as a trade-off,” Rutgers University neurobiologist John McGann says.

The myth of poor human olfaction is centuries old. And it is due for a thorough debunking.

“The human olfactory system is excellent,” McGann writes in a paper out today in Science that reviews the wide array of evidence on the human sense of smell. “We’re like lots of mammals with a perfectly good sense of smell, and if we paid more attention to it, I think we’d realize how important it is to us,” he tells me.

In fact, when you actually test humans on their ability to smell specific compounds, we’re pretty discerning. We can smell particles that are just two atoms large. And we can tell more than a trillion distinct odors apart.

But how did the myth get started? And why is it not likely to go away soon? Let’s take a walk through the research.

The scientist who started the myth

As McGann explains in the new paper, the myth began — as myths often do — with an overconfident male scientist.

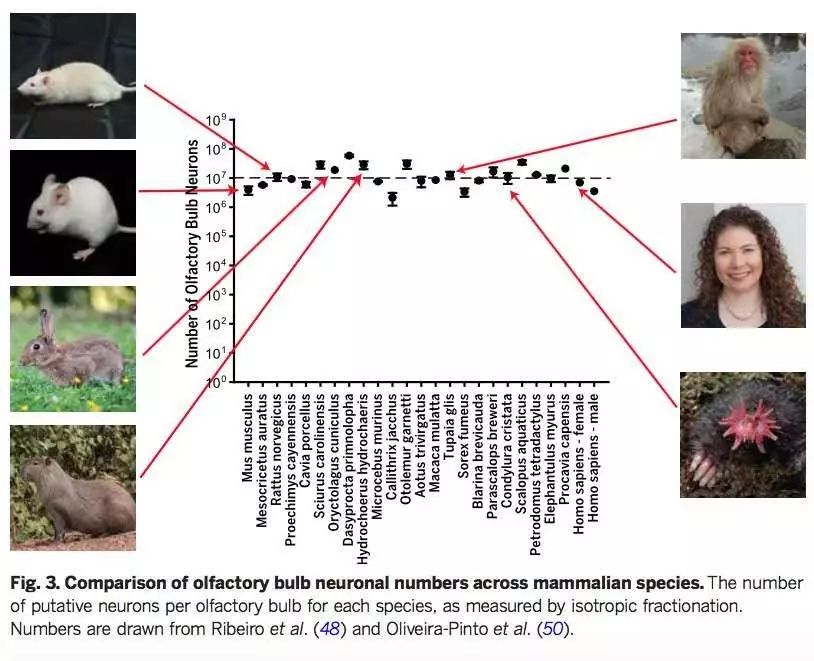

Paul Broca was a 19th-century anatomist in France who pioneered the study of the roles different brain regions play in speech and perception. In his dissections of the human brain, he noticed an oddity. The olfactory bulb — the region where we process smells — was relatively small in humans compared to other animals. He reasoned that this meant the sense of smell was less important for humans than other animals. (Not without some merit. Humans don’t leave urine markings or other forms of odor as a means of social communication, as many animals do.)

“Through a chain of misunderstandings and exaggerations beginning with Broca himself, this conclusion warped into the modern misapprehension that humans have a poor sense of smell,” McGann writes.

One reason the myth persisted is confirmation bias. This is often a problem in science: Initial, exciting results that ultimately end up being wrong are hard to dispel. After Broca, any evidence scientists found that contributed to the “humans smell poorly” theory was championed, while evidence to the contrary was dismissed.

For instance, when in the 2000s researchers revealed that 390 of the 1,000 odor receptor genes in the human genomes had no apparent function (since they don’t produce proteins), they instantly concluded this was further proof of humans’ disappointing olfaction. But they didn’t stop to think whether these 390 genes actually mattered when it came to actually sniffing out odors.

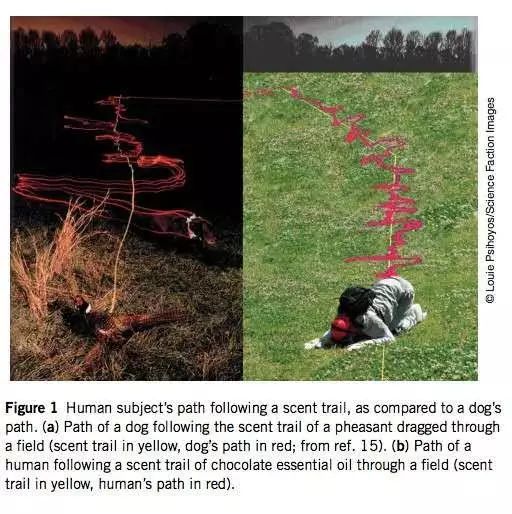

A key paper that helped chip away at the myth appeared in Nature Neuroscience in 2006. In the 2000s, 32 brave human research subjects got on their hands and knees in the middle of a grassy field, put their noses to the ground, and were told to follow a scent trail, like dogs. The scent in this case was a spritz of chocolate oil dragged across the lawn.

This wasn’t a prank. It was Serious Science.

“Two-thirds of the subjects were capable of following the scent trail,” the researchers wrote. Maybe we weren’t such bad sniffers after all.

Recent research reveals that even though the size of the human olfactory bulb is relatively small, it still has about roughly the same number of neurons as the olfactory bulbs of most other mammals. And “there is little support for the notion that physically larger olfactory bulbs predict better olfactory function, regardless of whether bulb size is considered in absolute or relative terms,” McGann writes.

And when you actually test out our ability to discern scents, it turns out we’re just as good as — if not sometimes better than — most other mammals.

Why we probably shouldn’t compare our sense of smell to a dog’s

It’s still often hard to directly compare the sense of smell between two animals, because we use them for wildly different tasks and social behaviors.

“So dogs like to sniff each other’s butts,” Paul Breslin, a scientist who studies odor perception with the Monell Chemical Senses Center, tells me (as I hold back laughter). “So you could ask the question — are humans not as good at sniffing butts as dogs? I don’t know. I haven’t sniffed that many people’s butts. I haven’t sniffed dogs’ butts, for that matter. Maybe if I sniffed as many butts as my dog does, I would notice they all smell different. So how do you compare them?”

For that matter, dogs — if they could talk — might be in awe of our ability to use our sense in cooking. How can we tell, just from sniffing, if certain combination of spices will taste good? It’s an incredibly complicated process.

Dogs do have a bit of a leg up on us when it comes to the biomechanics of sniffing. Their noses have what’s called a vomeronasal organ, which acts as a pump that pulls chemicals that are in liquids up into the nose. “That organ has its own receptors, its own nerve, and is processed in its own brain region,” McGann says. It means that dogs can pick up on odors trapped in liquids, whereas humans can only smell odors in the air. But it’s a debate whether the sensations picked up by this organ are “smell” or some other sense that humans don’t have access to.

When it comes to sniffing certain chemicals, humans often outperform rodents or monkeys. But then, some of these animals outperform us on other scents.

It’s not that some animals are vastly better than others across the board. We’re all adapted to be sensitive to different chemicals, and this is likely driven by evolution. For instance, McGann points out, humans perform poorly smelling the chemical 3-mercapto-3-methylbutan-3-ol. It’s a pheromone commonly found in cat urine. We don’t really need to smell that.

We undervalue our sense of smell

We don’t often consciously realize we’re using our sense of smell in decision-making.

“How many times in your life have you pulled some old leftovers, some old thing, out of the fridge and decided whether to eat it or not by a sniff?” McGann says. “You probably didn’t stop to think, ‘My sense of smell probably saved my life.’”