做一个自由的作家可能吗?不用担心急需用钱,不需赞美,不用担心这些杂事会如何反映在你的写作里,不用担心政治影响,不用担心出版商迫切地想出一本和上一本相似的书,或者更糟,符合当下趋势的书?

吃老本的村上春树

译者:李林治

校对:王乐颖

编辑:徐唱

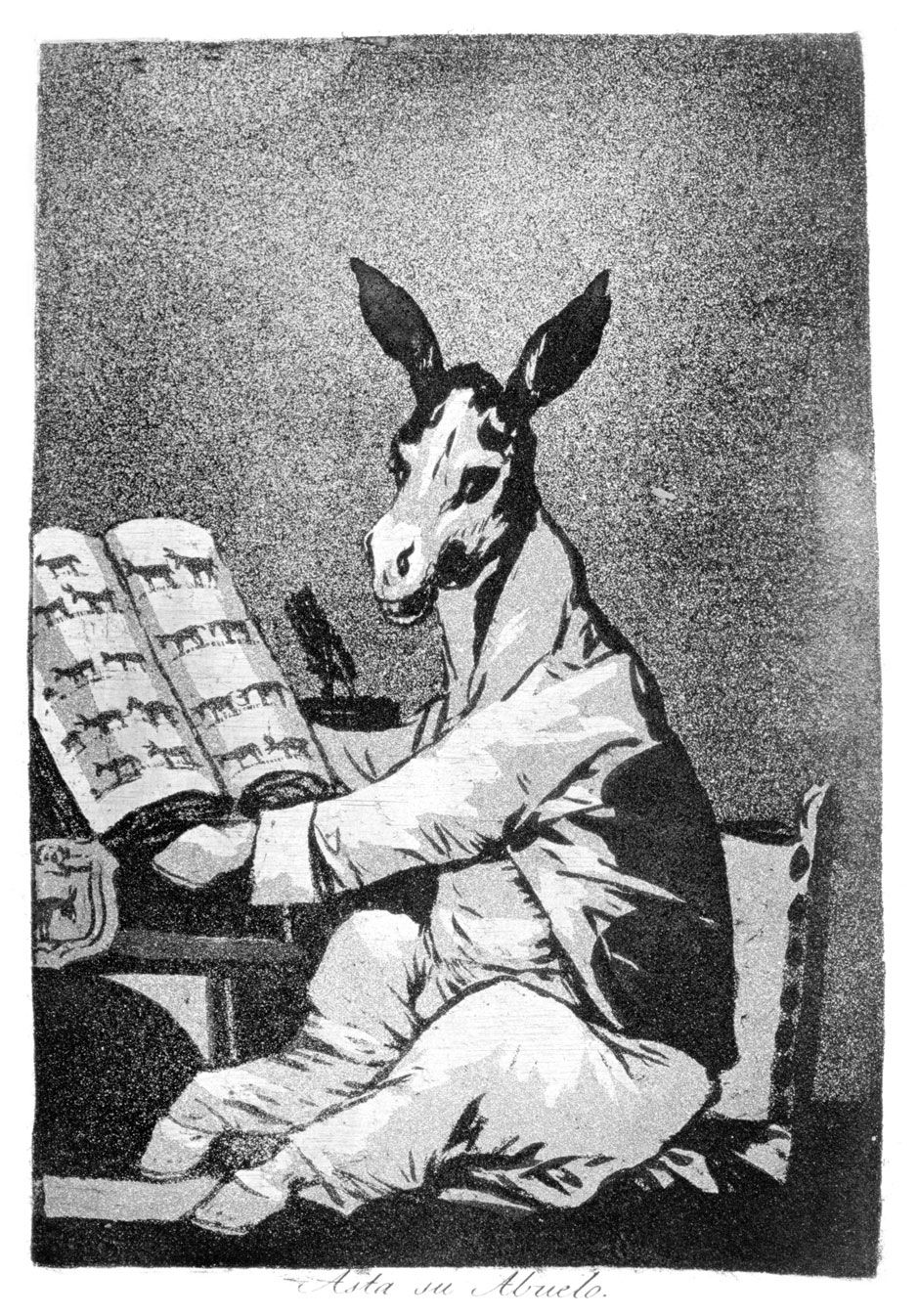

A Novel Kind of Conformity

有关遵循的新方法

本文选自

The New York Review of Books

| 取经号原创翻译

关注 取经号,

回复关键词“外刊”

获取《经济学人》等原版外刊获得方法

What happens when a multi-million dollar author gets things wrong? Not much. Take the case of Haruki Murakami and his recent novel Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and His Years of Pilgrimage. The idea behind the story is fascinating: What do you do when your closest friends eject you from the group without the slightest explanation? But the narrative is dull throughout and muddied by a

half-hearted

injection of Murakami-style weirdness–people with six fingers and psychic powers–that eventually contributes nothing to the very simple explanation of what actually happened. The book received mixed to poor reviews from embarrassed admirers and vindictive critics. Nevertheless, millions of copies were quickly sold worldwide and Murakami’s name remains on the list of likely Nobel winners.

如果身价百万美元的作者表现糟糕会怎么样?没什么大不了。想想村上春树和他的近期作品《没有色彩的多崎作和他的巡礼之年》。故事背后的想法令人着迷:如果被最亲近的朋友赶出你们的小团体,并且丝毫没有解释,你怎么办?但故事从头到尾都很乏味,加上敷衍了事的村上式怪异

——

例如拥有六指和通灵能力的人,最终也没道出究竟发生了什么。尴尬的崇拜者和报复性的批评者对小说的评价褒贬不一。不过,几百万书很快在全球范围出售,村上依旧是诺奖最有力竞争者之一。

half-hearted

/

ˌhafˈhärdəd/ adj.

done without much effort and without much interest in the result

半心半意的,敷衍了事的,不热心的

How many times would Murakami have to get things wrong, badly wrong, before his fans and publishers stopped supporting him? Quite a few. Actually, no matter what Murakami writes, it’s almost unimaginable that his sales would ever fall so low that he would be considered unprofitable. So the Japanese novelist finds himself in the envious position (for an artist) of being free to take risks without the danger of much loss of income, or even prestige.

村上还要写错多少次,错得多离谱,粉丝和出版社才会不再支持他?相当多次。实际上,无论村上写些什么,很难想象他的书会不畅销到让出版商认为他身上无利可图。这位日本小说家有冒险的自由,冒了险也不会怎么影响收入,或者名声。所以,他发现自己(作为艺术家)经常被嫉妒。

This is not the case with less successful authors. Novelists seeking to make a living from their work will obviously be in trouble if a publisher is not confident enough in their success to offer a decent advance; and if, once published, a book does not earn out its advance, publishers will be more hesitant next time, whatever the quality of the work on offer. Authors in this situation will think twice before going out on some adventurous limb. They will tend to give publishers what they want. Or try to.

在不那么成功的作家身上,情况就不同了。对于希望用作品谋生的小说家来说,如果出版商由于对他们作品缺乏信心、不支付像样的预付款,那他们明显就会遇到困难;如果书一旦出版,但没赚够预付款,无论在售书的质量如何,出版商下次都会犹豫。如此情况下,作家下次发挥想象写作前就会三思而后行。他们往往会写出版商想要的东西,或者尝试那么做。

The difficulties of the writer who is not yet well established have been

compounded

in recent years by the decision on the part of most large publishers to allow their sales staff a say in which novels get published and which don’t. At a recent conference in Oxford–entitled Literary Activism–editor Philip Langeskov described how on hearing his pitch of a new novel, sales teams would invariably ask, “But what other book is it like?” Only when a novel could be presented as having a reassuring resemblance to something already commercially successful was it likely to overcome the sales staff veto.

近些年来,由于大部分大出版商允许他们的销售人员决定哪些小说能发售,哪些不能,那些还未出名的作者的境况

恶化

了。在牛津最近的一次会议上

——

题为文学行动主义

——

编辑

Philip Langeskov

说道,当一听到有人推荐新小说,销售就会问,

“

和哪本书比较像?

”

只有当一本小说能和市面上已经取得成功的书相似时,才能避免被销售否决。

compound

/

ˈkämˌpound/ v.

to make sth bad become even worse by causing further damage or problems 使加重;使恶化

But even beyond financial questions I would argue that there is a growing resistance at every level to taking risks in novel writing, a tendency that is in line with the more general and ever increasing anxious desire to receive positive feedback, or at least not negative feedback, about almost everything we do, constantly and instantly. It is a situation that leads to something I will describe, perhaps paradoxically, as an intensification of conformity, people falling over themselves to be approved of.

但即使将财务问题放在一边,我也认为无论从哪个层面来说,写小说的人都越来越不愿意去冒险,这样的趋势和内心的渴望是一致的

——

越来越焦虑、做什么事都希望永远、马上得到好的回馈(至少不是差的)。也许有点矛盾,但我会把现在的情况形容为加强一致性,人们让自己堕落,寻求认可。

How can I flesh out this intuition? At some point it slipped into the conversation that high sales are synonymous with achievement in writing. Perhaps copyright was partly responsible. A novelist’s work is to be paid for by a percentage of the sales achieved. This aligns the writer’s and the publisher’s interests and gets us used to thinking about books in terms of numbers sold. Add to that the now obligatory

egalitarian

view of society, which suggests that all reader responses are of equal worth, and you can easily fall into the habit of judging achievement in terms of the number of readers rather than their quality.

我该如何厘清这个情况?某一时刻,人们会说高销量等于写作成就。也许版权是一个原因。小说家的收入根据销售量按百分比提成。这就使得作者和出版商的利益变得一致,让我们以销售数量评价一本书。加上社会上又流行

平等主义的

看法,也就是说所有读者的反应具有相同的价值,那么你就会很容易根据读者的数量而不是他们的质量来评判书的成就。

egalitarian

/ɪ,gælɪ'teərɪən/ adj. based on the belief that everyone is equal and should have equal rights

平等主义的

So, when praising a novel they like, critics will often give the impression, or perhaps seek to convince themselves, that the book is a huge commercial success, even when it isn’t. Such has been the case with Karl Ove Knausgaard. Apparently it isn’t imaginable that one can pronounce a work a masterpiece and accept that it doesn’t sell. Conversely, writer Kirsty Gunn recently spoke (again at the Literary Activism conference) of a

revelatory

moment when she, her husband, the editor David Graham, and others were celebrating another milestone in the extraordinary success of Yann Martel’s Life of Pi, which Graham was responsible for publishing in the UK. “Suddenly I had to leave the room,” Gunn said describing a moment of intense dismay. “I realized we had reached the point where we were judging books by their sales.”

所以,当批评家称赞一本小说时,他们会经常觉得,或者可能试着说服自己,这本书已经取得了巨大的商业成功,即便事实并非如此。

Karl Ove Knausgaard

便是如此。很明显,很难想象一个人会说一本书是杰作,还能接受它卖的不好。相反,作家柯斯蒂斯

·

冈恩最近说道(又是在文学行动主义会议上)一个

启示性的

时刻,当她,她的丈夫,编辑

David Graham

和其他人正在庆祝扬马特尔的《少年派的奇幻之旅》的非凡成功,

Graham

负责该书英国的出版。

“

突然间我不得不离开房间,

”Gunn

说那一刻无比灰心。

“

我发现我们已经开始根据销量去评价书了。

”

revelatory

/ˌrɛvəˈleɪtərɪ/ adj. A revelatory account or statement tells you a lot that you did not know.

揭示的

;

启示性的

Copyright has been with us two hundred years and more, but the consequent attention to sales numbers has been recently and dramatically intensified by electronic media and the immediate feedback it offers. Announce an article (like this one) on Facebook and you can count, as the hours go by, how many people have looked at it, clicked on it, liked it, etc. Publish a novel and you can see at once where it stands on the Amazon sales ratings (I remember a publisher mailing me the link when my own novel Destiny amazingly

crept

into Amazon UK’s top twenty novels–for about an hour). Otherwise, you can track from day to day how many readers have reviewed it and how many stars they have given it. Everything conspires to have us obsessively attached to the world’s response to whatever we do.

版权已经跟随我们两百多年了,但是对销售量的关注最近被电子媒体及其迅速的反馈加强了。在

FB

上发布一篇文章(比如这篇),你可以随着时间开始数,有多少人看了,点击了,喜欢了等等。发布一篇小说,你就马上能在亚马逊上的销售排名(我记得一个出版商发了我一个链接,当时我的小说《命运》一小时内

攀升

到了英国小说榜前

20

名)

crept

(

creep+into

)/

kriːp/ v. to move in a quiet, careful way, especially to avoid attracting attention

悄悄地小心行进,蹑手蹑脚地移动

Franzen talks about this phenomenon in his recent novel Purity, suggesting that, simply by offering us the chance to check constantly whether people are talking about us, the Internet heightens a fear of losing whatever popularity we may have achieved: “the fear of unpopularity and uncoolness….the fear of being flamed or forgotten.” Hence the successful novelist is constantly encouraged to produce more of the same. “It’s incredible,” remarks Murakami in an interview, “I write a novel every three or four years, and people are waiting for it. I once interviewed John Irving, and he told me that reading a good book is a mainline. Once they are addicted, they’re always waiting.”

Franzen

在他近期的小说中说到这个现象,他建议,仅仅让我们能够不断查看人们是否在讨论我们,英特网就加强了我们对于失去的恐惧。因此,成功的小说家不断被要求写相同的东西。

“

这很不可思议,

”

村上在一场访谈中说道,

“

我每三四年写一部小说,人们都在等。我曾采访过

John Irving

,他告诉我读好书是主流。他们一旦上瘾,就会一直等。

”

Well, is “addiction” what a literary writer should want in readers? And if a writer accepts such addiction, or even

rejoices

in it, as Murakami seems to, doesn’t it put pressure on him, as pusher, to offer more of the same? In fact it would be far more plausible to ascribe the failure (aesthetic, but not commercial) of Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and indeed Franzen’s Purity, not to the author’s willingness to take exciting risks with new material (Ishiguro’s bizarre The Buried Giant, for example), but rather to a tired,

lackluster

attempt to produce yet another bestseller in the same vein. Both writers have in the past taken intriguing distractions from their core business–Franzen with his idiosyncratic Kraus Project, Murakami with his engaging book on running–but when it comes to the novel, it’s back to the same old formula, though without perhaps the original inspiration or energy. Financial freedom is not psychological freedom.

那么,一个文学作家应该期待读者

“

上瘾

”

吗?如果作家接受了,就好像村上一样甚至

喜欢

,这种上瘾,难道不会有压力去写出更多相似的东西吗?实际上,将《没有色彩的多崎作》和弗兰岑的《纯洁》(审美而非商业)的失败,归因于对于相似作品疲态而又

暗淡

的追求,而非兴奋地尝试冒险(比如石黑一雄怪诞的《被掩埋的巨人》),是有道理的。两个作者过去都曾为他们的核心业务而分心

——

弗兰岑特殊的的克劳斯项目,村上令人着迷的跑步书

——

但说到小说,尽管也许没有最初的动力或能量,还是回到原来的模式。经济自由不是心理自由。

rejoice

/rɪ'dʒɔɪs/ n. to feel or show that you are very happy literary

喜悦,欣喜

lackluster

/'læk‚lʌstə/ adj. not exciting, impressive etc

毫无生气的;乏味的

Yet to create anything genuinely new writers need to risk failure, indeed to court failure, aesthetically and commercially, and to do it again and again throughout their lives, something not easy to

square with

the growing tendency to look on fiction writing as a regular career. “How have you survived as a writer twenty years and more?” a member of the public asked Kirsty Gunn after she had spoken of her absolute refusal to adapt her work to a publisher’s sense of what was marketable. “Day job,” she briskly replied.

但是,无论是从审美还是商业来说,真正想要创作,新作家需要冒险,甚至追求失败,在生命中一次又一次尝试,这和当下把写小说看成常规职业的趋势并不

相符

。

“

作为作家,你如何养活自己二十年及以上?

”

一个路人在柯斯蒂斯

·

冈恩完全拒绝接受出版商所定义的畅销。

“

日常工作

”

她轻巧地答道。

square (sth) with sth

if you square two ideas, statements etc with each other or if they square with each other, they are considered to be in agreement

(使某物)和某物一致

Is it really possible, then, to be free as a writer? Free from an immediate need for money, free from the need to be praised, free from the concern of how those close to you will respond to what you write, free from the political implications, free from your publisher’s eagerness for a book that looks like the last, or worse still, like whatever the latest fashion might be?

那么做一个自由的作家可能吗?不用担心急需用钱,不需赞美,不用担心这些杂事会如何反映在你的写作里,不用担心政治影响,不用担心出版商迫切地想出一本和上一本相似的书,或者更糟,符合当下趋势的书?

I doubt it, to be honest. Perhaps the best one can ever achieve is a measure of freedom, in line with your personal circumstances. Anyway, here, for what it’s worth, are two reflections drawn from my own experience:

说真的,我表示怀疑。根据你的自身情况,也许能得到的只是获得自由的方法。无论如何,不妨这样说,根据我的经验有两个反思:

1. So long as it’s compatible with regular writing, the day job is never to be

disdained

. A steady income allows you to take risks. Certainly I would never have written books like Europa or Teach Us to Sit Still without the stability of a university job. I knew the style of Europa, obsessive and

unrelenting

, and the content of Teach Us to Sit Still, detailed accounts of urinary nightmares, would turn many off. And they did; one prominent editor refused even to consider Teach Us, because “the word prostate makes me queasy.” Yet both books found enthusiastic audiences who were excited to read something different.

1.

只要这样的方式和传统写作兼容,日常工作永远不会受到

侮辱

。稳定的收入能让你承担一些风险。当然,我永远都不会在没有稳定工作的情况下,写诸如《梦回欧罗巴》或者《教我们静坐》之类的书。我了解《梦回欧罗巴》的风格,过分详尽又

没完没了

;《教我们静坐》中关于泌尿噩梦详尽的描述会令很多人失去兴趣。而事实也是如此;一位著名的编辑曾拒绝考虑《教我们静坐》,因为

“

前列腺这个词让我恶心

”

。

但两本书都有很热情的读者,兴奋地想要读些不同的东西。

disdain

/dɪsˈdeɪn/ v. If you feel disdain for someone or something, you dislike them because you think that they are inferior or unimportant.

轻蔑

unrelenting

/

ˌənrəˈlen(t)iNG/ adj.

an unpleasant situation that is unrelenting continues for a long time without stopping (

不愉快的情况) 持续的,不断的

2. When you’re trying to write something seriously new, don’t show it to anybody until it’s finished, don’t talk about it, seek no feedback at all. Cultivate a quiet separateness. “Anything great and bold,” observed Robert Walser “must be brought about in secrecy and silence, or it

perishes

and falls away, and the fire that was awakened dies.”

2.

当你尝试写些严肃的新作,不要给任何人看直到你写完,不要提及,完全不要寻求反馈。营造出安静的隔离感。

“

任何伟大又大胆的东西,

”

罗伯特华沙尔注意到,

“

必然在隐秘和沉默中产生,不然就会毁灭

消失

,曾经燃烧的火焰就会熄灭。

”

perish

/'perɪʃ/ v. to die, especially in a terrible or sudden way formal or literary

死亡 (尤指惨死或猝死)

Oddly enough these are conditions that are most likely to hold at the beginning of your writing career when you’re hardly expecting to make money and nobody is waiting for what you do. Which perhaps explains why the most

adventurous

novels–Günter Grass’s The Tin Drum, Elsa Morante’s House of Liars, Kingsley Amis’s Lucky Jim, J.D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye, James Baldwin’s Go Tell it on the Mountain, Nicholson Baker’s The Mezzanine, Thomas Pynchon’s V., Marilynne Robinson’s Housekeeping–are very often early works. Celebrity, it would appear, breeds conformity.

奇怪的是,这些最可能刚开始写作时候的状况

——

当时你几乎不期待赚钱,也没人等待你的作品。这也许就解释了为什么最

大胆创新

的小说

——

京特

·

格拉斯的《铁皮鼓》、艾尔莎

·

莫伦特的《谎言满屋》、金斯利

·

艾米斯的《幸运的吉姆》、

J·D·

塞林格的《麦田里的守望者》、詹姆斯

·

鲍德温的《向苍天呼吁》、尼尔森

·

贝克的《夹层厅》、托马斯

·

品钦的《

V

》、玛丽莲

·

罗宾逊的《管家》

——

通常都是很早期的作品。名气,这样看来,会孕育自我重复。

adventurous

/əd'ventʃ(ə)rəs/ adj. not afraid of taking risks or trying new things

大胆创新的

#访问取经号官网#

网站域名

qujinghao.com

, 即“取经号”的全拼

#读译交流#

后台回复

读译会

,参与取经号Q群交流

#外刊资源#

后台回复

外刊

,获取《经济学人》等原版外刊获得方法

#关注取经号#

扫描

二维码

,关注跑得快的取经号

(

id: JTWest

)