Children with leukemia(白血病) in a Fujian hospital.

Holding her six-year-old son, Deng Na’s looks into the camera, her face both tired and determined. The picture accompanying the online crowdfunding call for her son Chen Junnan’s bone marrow transplant was taken in a hospital close to Beijing, where Deng, 27, has spent much of her time since Junnan was diagnosed with leukemia four years ago.

A screenshot of the crowdfunding page Deng Na started to raise funds for her son Junnan’s bone marrow transplant on Tencent Gongyi. (WeChat)

Deng, who used to work as a nurse in her hometown in Guangdong province, turned to crowdfunding to meet her urgent financial needs after her son’s cancer returned. Since she posted about her son’s condition on Tencent Gongyi, an online charity platform run by technology giant Tencent, donations by over 12,000 people came to almost 30% of the 500,000 yuan ($72,500) she needed. “We are a poor family and still owe our friends and family 200,000 yuan. So now I want to try this,” she says.

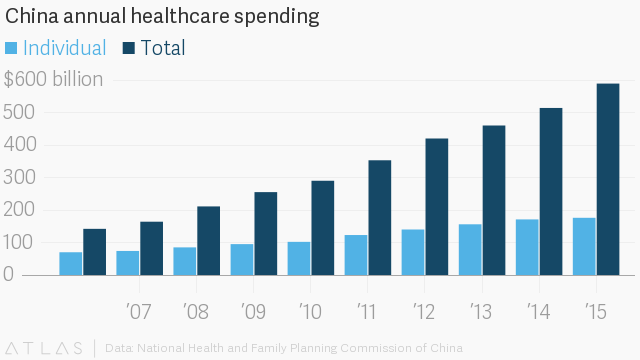

People in China with medical needs are increasingly turning to the internet for financial assistance as medical costs soar. While medical insurance has rapidly expanded to become nearly universal in recent years—97% of the population is part of one of three public insurance schemes—the money doesn’t go far. Reimbursement rates differ widely by region and type of treatment. Out-of-pocket expenses account for about 30% of all medical costs, according to the Chinese ministry of finance, compared to about 12% in the US. In a bid to address the problem, China this month ordered hospitals to begin restricting drug surcharges from later this year, though other kinds of charge will still be allowed.

Online fundraising has become part of an overall strategy to meet costs when insurance is insufficient, in addition to family savings, loans, and funds from foundations, says Wu Yue, a heart surgeon in Beijing’s Fuwai hospital. Like many Chinese doctors, Wu regularly directs patients in need towards alternative sources for funding. “It rarely suffices, but it lowers financial pressure on families. Even if it just means a few thousand less to pay back.”

The Chinese government welcomes the trend too. The 2016 Charity Law relaxed strict controls on fundraising in an attempt to promote a more diverse social service sector, for example. Medical-sector planning documents state that charity support should be “proactively enlisted” to supplement the still incomplete and unfair insurance system—as citizens whose registered home address is in a rural area, Deng and her son receive lower coverage than urban citizens.

“If we were Beijing residents, things would look very different,” Deng muses in a voice message.

Millennial generosity

The surge in online charitable giving is being driven largely by a young generation that is less influenced by the legacy of the socialist planning economy in which the state is supposed to provide for all social needs, says Deng Guosheng, vice-director of the Institute for Philanthropy at Tsinghua University in Beijing.

“Online individual giving is growing very, very fast,” he says, and “young people give the most.” According to a recent analysis by the institute, while those born after 1980 gave the most in monetary terms, the largest group of givers were those born after 1990.

Wu Jie (no relation to the doctor), a 26 year-old filmmaker from Yunnan province, regularly shares medical cost crowdfunding notices in his friend group on WeChat, China’s largest chat app. “Online giving is convenient, a product of the current shortcomings of the medical system and the development of online media,” says Wu. Even if most people just give 5 or 10 yuan, he says, “it adds up—we all have many friends on social media.”

Fourth-year university student Cheng Zijun also chips in when he can, “especially when it concerns a medical emergency. The costs of a serious illness could bring down any family,” says the 20 year-old, based in Hangzhou, Zhejiang province.

The two are also unfazed by scandals challenging the credibility of online charity, such as the recent case of a media worker in Shenzhen whose emotional essay addressed to his five-year-old daughter, a leukemia patient, raised nearly 75 times the daughter’s treatment costs. The story led to a public outcry in December, especially after it became known the author owned several apartments.

“Completely unacceptable,” says Wu, the film maker. “How can a home-owner ask for money in a country in which so many own nothing at all?” Wu is also angry at China’s inequality, rooted in his own experience of moving from rural Yunnan to the country’s capital. “The gap is just too big.”

Trust issues

To address problems of public trust, crowdfunding platforms have added security features. On Deng’s page for her son, 140 people, mostly contacts from her Guangdong home region, have confirmed her story. “This is my former classmate! The information she provides is factual,” one writes. There are also uploaded medical statements and a notice from Deng’s home village government confirming that the family lives on dibao, a low-welfare allowance.

But often it is the detailed stories written by patients or their relatives that do most to establish trust and trigger donations in a country where charitable giving remains a relative novelty. In 2014, total giving in China was about one-twentieth of that in the US. Per capita donations are even lower. In the 2015 World Giving Index, China ranked 144 among 145 countries; only Burundi ranked lower.

Well-written appeals and extreme stories involving young children—like the Shenzhen scandal—are most likely to find funding, says Zheng Yijing, an employee at charity Shanghai United Foundation. Personal networks are also critical, as online medical-donation networks operate like a technology-fueled expansion of China’s “society of acquaintances,” with the traditional network of relatives, friends, and people from the area amplified by the reach of social media, Zheng adds.

Wu Congzhi in his rented home in Jiangxia, a mostly rural district on the outskirts of of Wuhan. Wu’s mobility is severely limited

For some, like Wu Congzhi, 28, a former construction worker with a serious form of arthritis, the power of emotional appeals are limited. “I am a young man, and I am not dying,” says Wu, who failed to raise enough money online for a new hip on popular platform Qingsong Chou (“Relaxed Fundraising”). Chronic diseases like Wu’s can be among the most difficult to find funding for, as they fall outside most insurance schemes and are also ignored by most medical assistance foundations.

Wu, who has a limited family network having lost both his parents and a brother at a young age, initially hesitated to ask strangers for money. “No one wants to be dependent,” he explains in his unheated room in a town outside the city of Wuhan. But, encouraged by a friend, he decided to try crowdfunding, and quotes a line that also features prominently on his crowd-funding page: “If I get the right treatment, I could make a much bigger contribution to society.”