中文导读

朝鲜半岛核问题进一步加剧,美国试图通过军事威胁和经济制裁迫使朝鲜放弃核武的努力,而中国是其中的重要一环。鉴于中国是朝鲜最重要的贸易合作伙伴,美国在国际社会上对中国频频施压,要求中国对朝鲜实施更为严苛的经济制裁。中国推动半岛核问题和平解决的努力是毋庸置疑的,但对于美国干涉南海主权问题和萨德系统的部署,我们必将持坚定的反对立场。

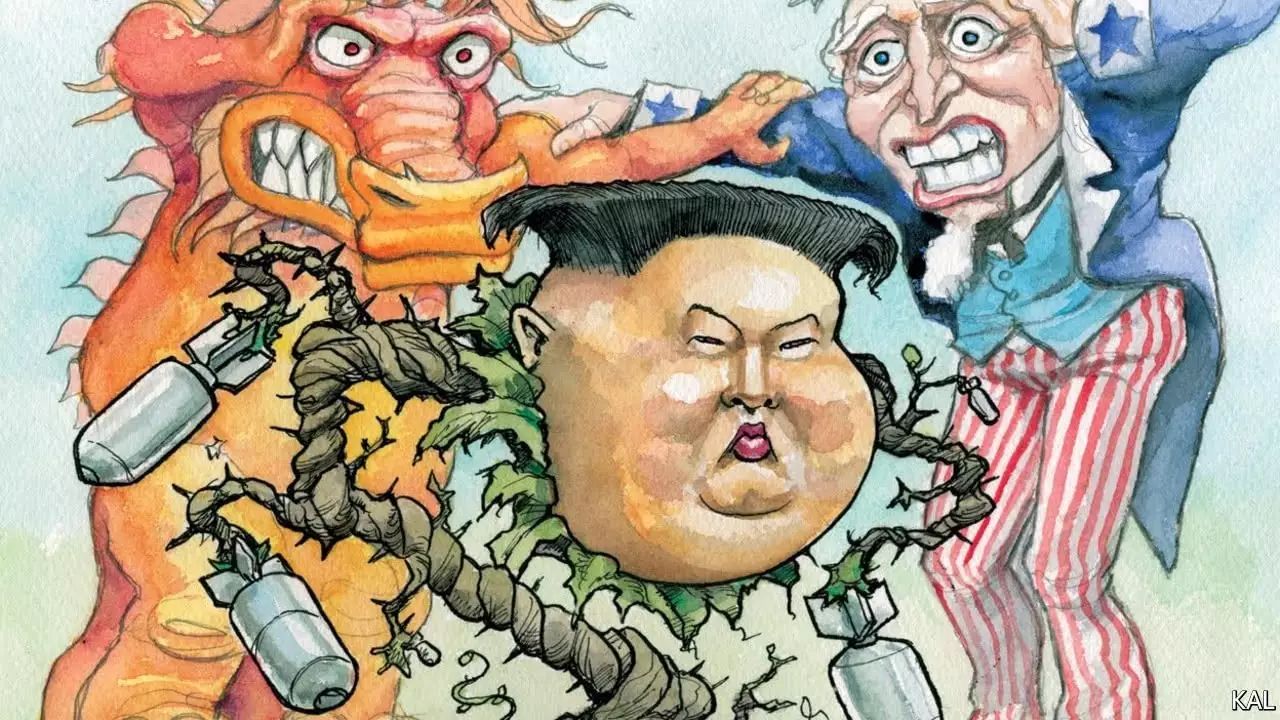

America’s message to China: either you stop North Korea building nuclear missiles, or we will

ALL serious governments think, hard, about unthinkable horrors. For America, China and other Asia-Pacific powers, few potential events are as grim to contemplate as a war involving North Korea, or that country’s violent collapse.

There are reasons why the world does not seek to topple North Korea’s impetuous young leader, Kim Jong Un. For one, his regime—a Stalinist take on a feudal monarchy, funded by mafia-like criminality around the globe—keeps artillery pieces and rocket-launchers aimed at the South’s booming capital, Seoul, 35 miles from the border between the two Koreas. To convey the costs of that conflict, American experts recall the grimmest examples of urban destruction in Chechnya, and imagine evacuating millions of civilians from Seoul and its suburbs, under fire.

Chinese leaders have their own nightmare scenario: the chaotic fall of the Kim regime, sending millions of refugees into north-eastern China as a race begins for control of the North’s nuclear arsenal. In the medium term, China’s government fears a unified, pro-Western Korea on its border. The jumpiest Chinese imagine gum-chewing Marines and American spy stations rising on the Korean banks of the Yalu river, yards from China—despite discreet assurances that America has no intention of enlarging its military footprint in Asia, should Korea peacefully reunify.

Seoul’s vulnerability as a hostage city helps to explain why both Republican and Democratic administrations have spent years hoping that diplomacy and economic pressure will dissuade North Korea from building nuclear weapons. To date, these hopes have been in vain. Chinese leaders also fear the destabilising effects of North Korea’s weapons programmes, and have signed up for somewhat tighter sanctions. But in their internal hierarchy of horrors, the Kim regime’s collapse frightens them more. As a result China has, until now, been willing to consider all forms of sanctions except those painful enough to work.

Chinese officials, who struggle to meet senior North Koreans, continue to insist that they have limited political leverage over the Kim regime. That is sophistry: China has unrivalled economic power over North Korea, including a stranglehold on its energy supplies. China also continues to claim that an anti-missile defence system recently installed by America in South Korea, THAAD, undercuts China’s ability to deter external threats. That is a nonsense to which Americans reply, if you want THAAD gone, deal with North Korean nukes.

Something big has changed. In developing intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) that could hit American cities, and repeatedly testing them, the Kim regime directly threatens the American homeland. Yet in the upper ranks of the American government there are flickers of optimism, and they concern China. Perhaps its president, Xi Jinping, still fears instability on his border more than a nuclear-armed North Korea—American opinions are divided. But Team Trump is determined to convince Mr Xi that he has his hierarchy of horrors in a muddle. The new message: if China will not act to halt the North Korean missile threat, America will. As a result, it is North Korean ICBMs that threaten the very chaos that leaders in Beijing fear most.

On June 3rd James Mattis, the defence secretary, told the Shangri-La Dialogue, a gathering of Asian government leaders and military brass in Singapore, that North Korea’s weapons programmes are a “clear and present danger” to America. Mr Mattis is a figure of rare credibility within the Trump administration, revered by his peers as a “warrior-monk”—a ferocious battlefield commander who carried works of Roman philosophy into combat, and prodded his officers to think hard about the ethics of killing. Still, his audience in Singapore was anxious as he began. Asian governments want to know whether Mr Trump, a man who seems more concerned with interests than values, might do a deal with China, trading help with North Korea for a Chinese sphere of influence. They fear that America will bluster, then look the other way as China builds airstrips and military bases on disputed reefs in the South China Sea. Mr Mattis tried to assure them that no such trade-off exists. He declared that America will not accept unilateral, coercive moves to change facts on the ground, and accused China of showing “contempt” for neighbours.

Cynics may remain sceptical, believing that Mr Trump is quite capable of a trade involving Chinese reef-grabbing for effective Korean sanctions. The best counter-argument within the American government is that such a binary trade-off would not be clever dealmaking. If possible, it is argued, America should avoid confusing the urgent (curbing North Korea) with the enduring (managing China’s long-term rise within a rules-based order).

An appeal to self-interest

Following Dwight Eisenhower’s dictum that “If a problem cannot be solved, enlarge it”, the Trump administration hopes to engage China on a broader range of interests. There are, for instance, Uighur militants from western China with ties to extremist networks in Afghanistan, a country about which America knows a lot. North Korean cyber-attackers have used China as a base: America calls that an affront to Chinese sovereignty.

Mr Trump’s affection for Mr Xi after a meeting at Mar-a-Lago, the American president’s Florida country club—“I think I like him a lot, I think he likes me a lot,” he said afterwards—may be more conditional than Asian allies fear. Mr Trump is said to feel that he received personal assurances about unprecedented Chinese pressure on North Korea. If disappointed, he has a whole tough-on-China agenda left over from his presidential campaign.

All-out war may be unimaginable. But if North Korea continues to sprint for ICBMs, America’s appetite for risk will rise sharply, and military options will gain a harder edge. China has for too long tolerated North Korean provocations in exchange for stability on its borders. Time to choose.

——

Jun 8th 2017 | United States | 951 words