中文导读

从施行独生子女政策到全面开放二胎,人口政策变迁的背后反映的正是中国人口结构的变化。过去,人口膨胀成为中国经济发展的负担,于是政府推行计划生育,严格限制人口规模。可现如今,人口老龄化加剧,不仅给社会保障体系造成了巨大的压力,还影响了劳动力市场的发展。为了鼓励生育,政府采取了一系列措施,但效果并不显著,人们的生育欲望仍旧呈现低迷状态。

China’s one-child policy was illiberal and unnecessary. Will its efforts to boost births be more enlightened?

WHEN Li Dongxia was a baby, her parents sent her to be raised by her grandparents and other family members half an hour from their home in the northern Chinese province of Shandong. That was not a choice but a necessity: they already had a daughter, and risked incurring a fine or losing their jobs for breaking a law that prevented many couples from having more than one child. Hidden away from the authorities, and at first kept in the dark herself, Ms Li says she was just starting primary school when she found out that the kindly aunt and uncle who often visited were in fact her biological parents. She was a young teenager before she was able to move back to her parents’ home.

Ms Li is now 26 and runs her own private tutoring business. The era that produced her unconventional childhood feels like a long time ago. The policy responsible for it is gone, swapped in late 2015 for a looser regulation that permits all families to have two kids. These days the worry among policymakers is not that babies are too numerous, but that Chinese born in the 1980s and 1990s are procreating too little. Last month state media applauded parents in Shandong for producing more children than any other province in 2017. It called their fecundity “daring”.

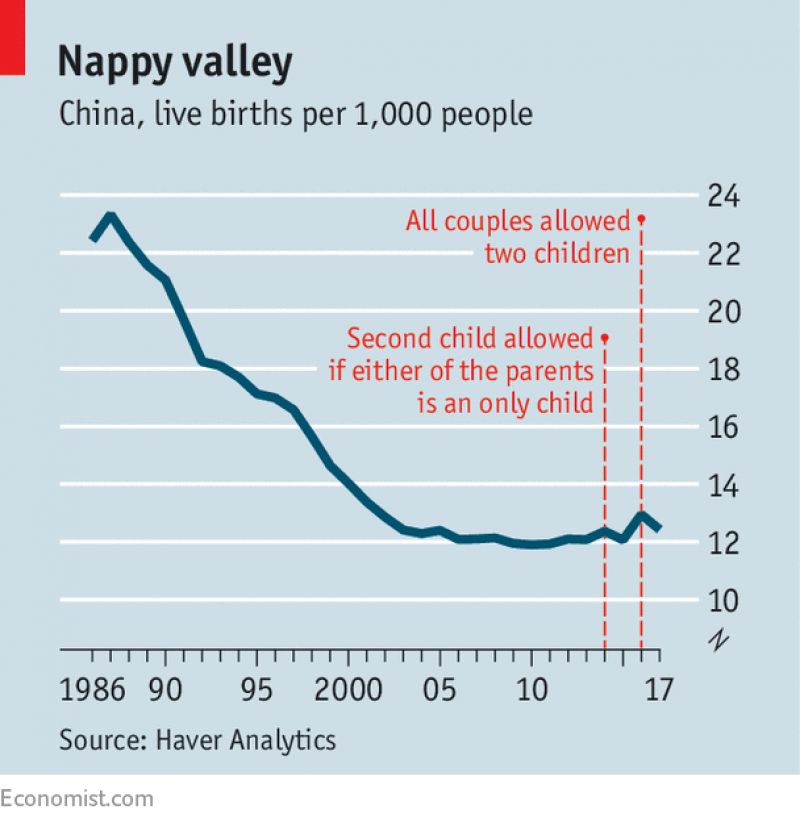

At the root of this reversal is growing anxiety about China’s stark demographic transition. Although the birth rate has recovered slightly from a trough in 2010, women still have less than two children on average, meaning that the population will soon begin to decline. The government predicts it will peak at a little over 1.4bn in 2030, but many demographers think it will start shrinking sooner. The working-age population, defined as those between 16 and 59 years old, has been falling since 2012, and is projected to contract by 23% by 2050. An ageing population will strain the social-security system and constrict the labour market. James Liang of Peking University argues that having an older workforce could also end up making Chinese firms less innovative than those in places such as America which have a more favourable demographic outlook.

Unwinding the one-child policy was supposed to help. But figures released in January confirm that after briefly boosting birth rates, its effect is petering out (see chart). Chinese mothers bore 17.2m babies last year, more than before the rules were relaxed but 3.5% down on 2016. Wang Feng of the University of California, Irvine, says the number of births was 3m-5m lower than the projections from the family-planning agency when the authorities were debating whether to change the policy, and below even sceptical analysts’ estimates.

The reason is that as China grows wealthier—and after years of being told that one child is ideal—the population’s desire for larger families has waned. Would-be parents frequently tell pollsters that they balk at the cost of raising children. As well as fretting about rising house prices and limited day care, many young couples know that they may eventually have to find money to support all four of their parents in old age. Lots conclude that it is wiser to spend their time and income giving a single sprog the best possible start in life than to spread their resources across two.

Meanwhile, more education and opportunity are pushing up the average age of marriage (that is a drag on fertility everywhere, but particularly so in societies such as China’s where child-bearing outside wedlock is taboo). Women thinking about starting or expanding a family still have to weigh the risks of discrimination at work. Since the one-child policy was relaxed, many provinces have extended maternity and paternity leave, but are not always ready to enforce the rules when employers break them.

The Communist Party appears to recognise that it needs to do more to lower these barriers. A population-planning document released last year acknowledged that the low birth rate was problematic and referred to a vague package of pronatalist measures that it would consider in response. The following month China Daily quoted a senior official who said that the government might introduce “birth rewards and subsidies” to overcome the reluctance of many couples to multiply.

Yet the lacklustre performance of pronatalist policies elsewhere in the world suggests that it would take vast investments to raise fertility, and that making child care cheaper should be a priority. At present it is difficult to imagine the party doing enough to make a difference—not least because it has yet to abandon its official position that some population-control measures remain essential. Leaders may be hesitating to ditch the two-child rule completely while they work out what to do with the army of bureaucrats charged with keeping birth rates low. They are probably also nervous that making too swift a U-turn will be seen as an admission that the party’s draconian policies, which led to forced abortions and sterilisations, were misguided.