FROM “Gangnam Style” and competitive electronic sports to kimchi-flavoured pot noodles, South Korea’s cultural exports are eagerly consumed around the world.Filipinos are hooked on its dramas. The French love its pop music and its films. In 2013 South Korea raked in $5 billion from its pop-culture exports. It has set its sights on doubling that by2017.

从江南style和有实力的电子竞技到韩国老坛泡菜方便面,韩国的文化出口在全世界大受欢迎。菲律宾人迷上了韩剧。法国人喜欢它的流行音乐和电影。2013年韩国通过流行文化出口吸金50亿美元,并计划2017年翻一番。

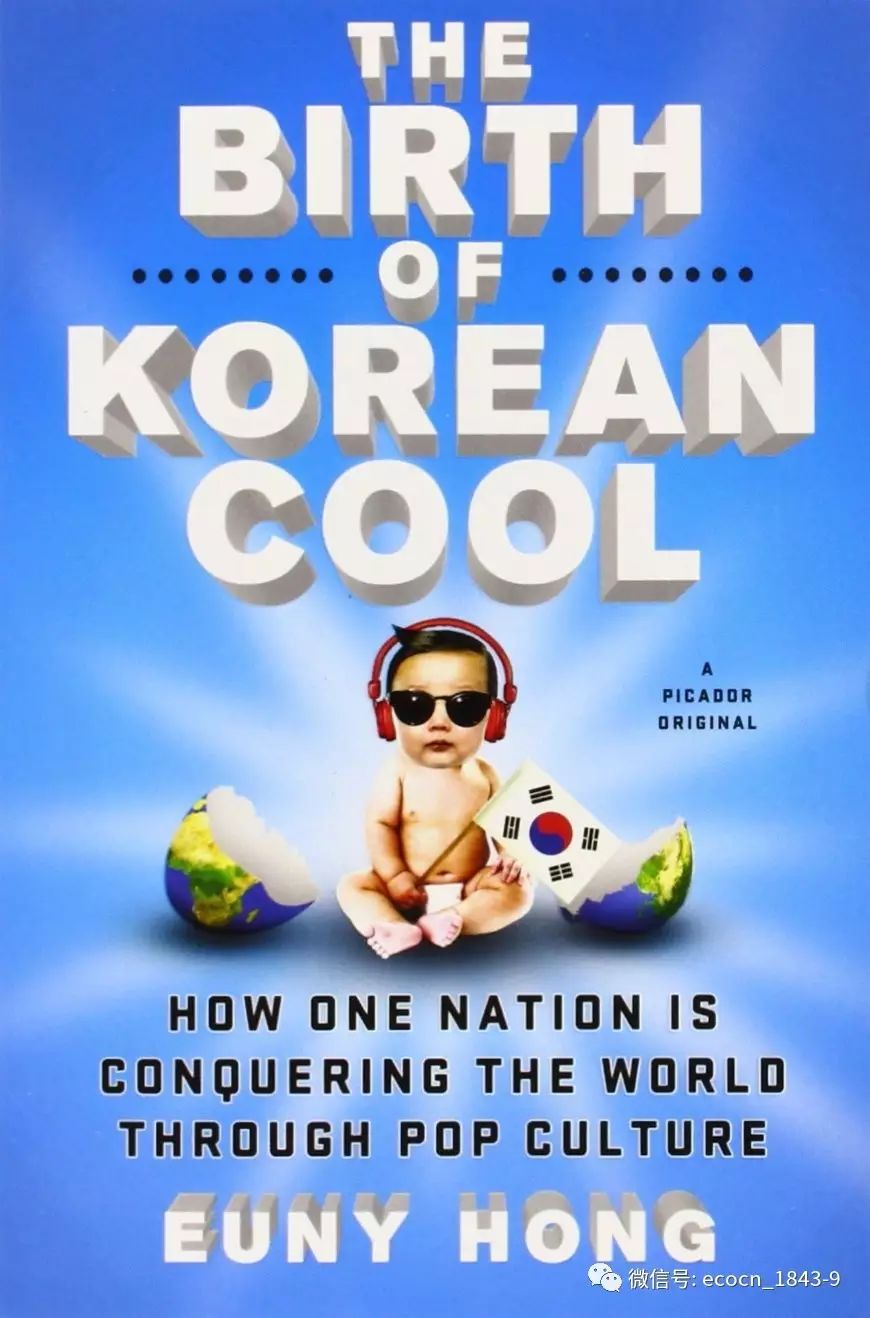

Much has changed since 1985, when Euny Hong, a Korean-American journalist and author of a new book called “The Birth of Korean Cool”, arrived in Seoul. South Korea was most definitely not hip. Its musicians had been muzzled by censorship, and busking, considered a form of protest, had been banned. The country had no mods, rockers or hippies. Dramas were “provincial and tedious”.

1985年,韩国裔美国记者,新书“酷棒子诞生记”的作者Euny Hong到达首尔,从那以后有了很多改变。当时韩国绝对是最不时髦的。音乐家们因为被审查而保持缄默,走上街头卖艺,被视为抗议,被压制。这个国家没有摩登派、摇滚乐家和嬉皮士。电视剧又土又无聊。

Over the next six years Ms Hong witnessed the swiftest part of the country’s economic development, “the painful period between poverty and wealth”. She recalls the anomalies of the time: newly wealthy women wearing mink coats at the fish markets; frequent power cuts in her family’s flat, the poshest in a posh district.

接下来的六年里,Hong女士目睹了这个国家经济增长最快的部分,“贫穷和富有间痛苦的时期”。她回忆起那段时间的反常:新生的富婆在鱼市里穿着貂皮大衣;她的顶级公寓经常断电。

From this unpromising position South Korea managed to charge past Japan to become Asia’s foremost trend setter, and Ms Honginter views superstars, chefs and cultural critics to discover why. She finds that cool can be manufactured, up to a point. South Korea’s is a side-effect of the culture-exporting machine that was created at the end of the 20th century and has been nurtured by the government ever since.

韩国从一个没有希望的境遇迅速超过了日本成为了亚洲潮流引导者。Hong女士采访了很多大明星,厨师和文化评论家来揭示原因。她发现在一定程度上酷是可以制造的。韩国的酷是20世纪文化输出大潮的副产品,并从此被政府鼓励。

The Asian financial crisis of 1997 revealed a weakness in Korea’s reliance on big conglomerates, and Kim Dae-jung, the president, responded by pushing the development of the IT and content (film, pop and video-games) industries. Firms folded or reorganised: Samsung moved into digital TV and mobile phones. According to Ms Hong, without the crisis there would probably have been no hallyu, the Korean cultural wave that has rolled through Asia for the past decade.

1997年的亚洲金融危机揭露了韩国依赖联合企业的弱点,总统Kim Dae-jung用推动发展IT和文化产业(电影,流行音乐和电视游戏)来应对。企业倒闭或者重组:三星进军数字电视和手机。据Hong女士说,要是没有金融危机说不定就没有接下来席卷整个亚洲几十年的韩国文化潮——“韩流”。

Tax incentives and government funding for start-ups pepped up the video-game industry. It now accounts for 12 times the national revenue of Korean pop (K-pop). But music too has benefited from state help. In 2005 the government launched a $1 billion investment fund to support the pop industry. Record labels recruit teens who undergo years of gruelling training before their public unveiling.

对起步企业的减税和政府资助鼓励了电视游戏行业的发展。现在它是韩国流行音乐税收的12倍。但是音乐也受到了政府的帮助。2005年政府拿出10亿美元来支持流行音乐产业。制片商招收十几岁的人,这些人出道前会经受大量繁重的训练。

It is true that creativity can be limited by this work ethic and the accompanying fear of failure. (In Korea’s bubble-gumball ads and Europop-inspired tunes, voices come second to synchronised dancemoves.) But this weakness has been turned to an advantage: conservatism is now a conscious strategy for the export market. K-pop has stronger global appeal than Japan’s J-pop, which tends to be less puritanical. Dramas focus on courtship and family roles. Actors and singers promote Korean tastes, in a reassuch as cosmetics, and in turn beauty businesses hire stars to promote their products.

职业道德和担心失败会约束创造力。(在韩国口水歌和欧陆流行乐,声音跟伴舞比是第二位的。)但是它的缺点变成了优点:保守成为了对外市场的策略。韩国流行音乐比日趋守旧的日本流行音乐在全球更有吸引力。电视剧主要是爱情和家庭角色。演员和歌手提升了韩国像化妆品之类的品味,反过来和美有关的生意会雇明星来提升他们的产品。

Ms Hong describes Korea’s approach to culture as “a full-on amphibious attack”. She talks to some of those who have worked behind the scenes: one official organised flash-mobs around France to demand a K-pop concert; another spirited “What Is Love”, South Korea’s first so-called K-drama, into Hong Kong inside a diplomatic pouch.

Hong女士描述韩国的文化政策是“全面的两栖进攻”。她跟一些幕后工作者谈过:一个官员在法国组织了快闪族来要求一场韩国演唱会;另一个把所谓的第一部韩剧“什么是爱”放在外交邮袋里偷偷带进了香港。

The “attack” works because the pop culture it peddles is more palatable to other Asians than that of former aggressors, such as Japan or China. Korean dramas are so popular in the Philippines that they have inspired local remakes in Tagalog. “Winter Sonata”, another drama, was a hit in Iraq and Uzbekistan. Japan is now using the Korean model as inspiration: in what is perhaps the best evidence of its own waning power as a trendsetter, it has launched a $500m fund to invest in “Cool Japan”.

“进攻”之所有有效是因为他们推送的流行文化比之前的像韩国和中国侵略者更加令人喜欢。韩剧在菲律宾非常流行,以至于当地人重新用塔拉加语重新拍了一遍。另一部韩剧冬日恋歌则在伊拉克和乌兹别克斯坦非常火。现在日本用韩国模式作灵感:日本给爽酷日本投资5亿美元就是他们作为潮流引导者减弱的最好证据。

PSY, the rapper behind “Gangnam Style”, was not part of the national strategy. His song, with its 2 billion YouTube views,mocks the effeteness of a generation of South Korean nouveaux-riches. Its success may therefore testify to the limits of packaging cool, but it also shows the world’s readiness to revel in Korea’s cultural charms.

江南style里的说唱歌手鸟叔,不是国家策略的一部分。他那有20亿YouTube观看量的视频,讥讽了韩国土豪的腐朽。它的成功可能会因此证明了包装出来的酷是有局限性的,但也表现了世界已经准备好陶醉于韩国文化魅力了。