中文导读

1955年印度总理参观苏联后对其共产主义化进程大为惊叹,以为这也许是将世界变得和平昌盛的最好途径。但一百年的时间揭晓了答案。由于共产主义化对农业资源的过度剥削,农民阶级的激烈反抗,社会资源没办法分配给有巨大需求的城市劳动力,从而大投入的社会工业发展也就大受限制,最终导致悲剧性的失败。

One hundred years after the Russian revolution, what remains of its economic ideas?

IN 1955 Jawaharlal Nehru, the prime minister of India, embarked on a 16-day tour of the Soviet Union. He was like a “kid in a candy store”, according to one editor of his letters. Besides the Bolshoi ballet and the embalmed corpse of Stalin, he visited a Stalingrad tractor works, a machinery-maker in Yekaterinburg and an iron-and-steel plant in Magnitogorsk. In a letter, he wondered if the Soviet Union’s economic approach, “shorn of violence and coercion”, could help the world achieve peace and prosperity.

The answer, of course, was “no”. But Nehru concluded otherwise, incorporating Soviet ideas into India’s five-year plans and welcoming Soviet aid, equipment and expertise. In the year of his visit, the Russians set up a steel factory in what is now the Indian state of Chhattisgarh. It became India’s main supplier of rails.

Nehru was not alone. The Soviet model impressed many leaders in the poorer parts of the world. Even today, according to Charles Robertson of Renaissance Capital, an investment bank, “more than a few suggest that a Stalin might be needed to kick-start industrialisation” in poor countries. The Soviet approach rested on a variety of arguments, notes Robert Allen of Oxford University, such as the need for a big push in industry, the abundance of rural labour and the superiority of collective farming.

The Soviets believed that industrialisation would succeed en masse or not at all. Those steel plants, tractor factories and machinery-makers needed to operate on a big enough scale to justify the heavy upfront cost of building them. And the success of any one industrial venture depended on complementary investments in others. Upstream suppliers need downstream buyers and vice versa. Yevgeni Preobrazhensky, a Bolshevik economist, argued that a broad advance was needed across the whole industrial front, not an “unco-ordinated advance by the method of capitalist guerrilla warfare”.

The workers for this industrial advance could be found in abundance on the farms, the Soviets believed. Agriculture was so overmanned it could lose millions of field-hands without much damage to the harvest. That was just as well, because the remaining peasantry would have to feed the factory workers as well as themselves. One way or another, resources would have to be transferred from the countryside to the cities. By organising the peasantry into collective farms, the Soviets hoped to make them more productive—and easier to “tax”. A collective farm was, they believed, easier to collect from.

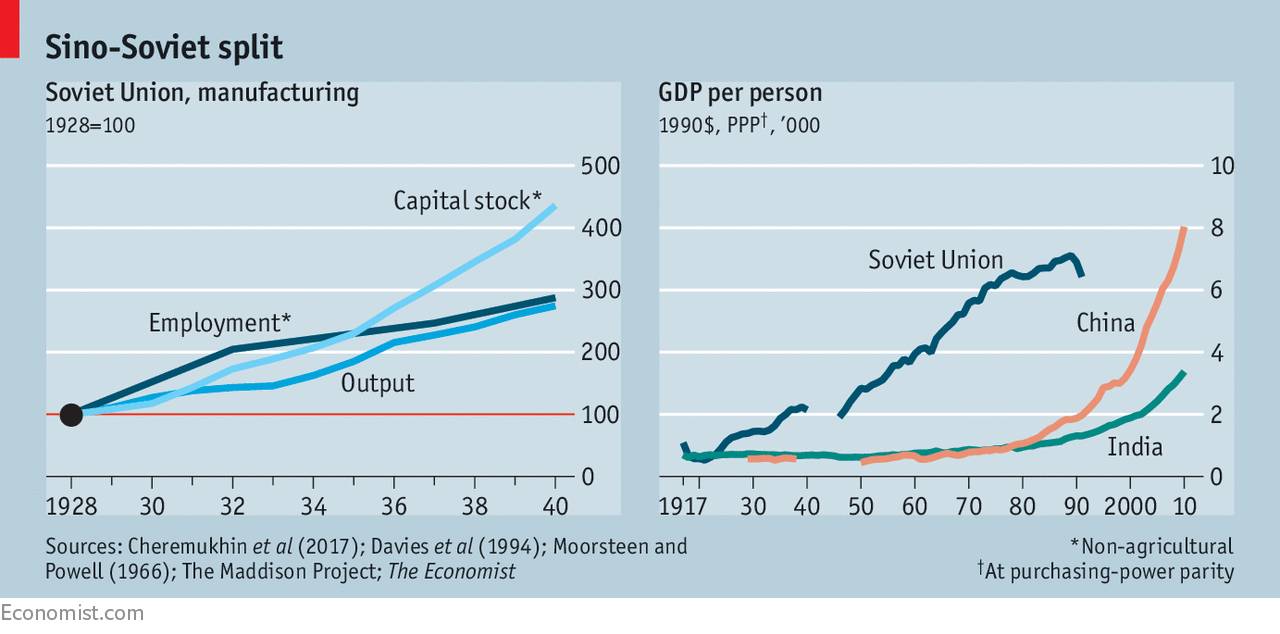

The Soviet approach succeeded in industrialising the economy. Between 1928 and 1940 its manufacturing output grew by over 170%, even as the rest of the world wallowed in the Depression. By the second world war, it was well on its way to becoming the industrial candy-store so admired by Nehru. This brute industrial expansion did not, however, validate the theories underlying the Soviet approach. To increase manufacturing output by 170%, the Bolsheviks had to increase inputs by even greater percentages: the non-agricultural workforce had to grow by almost 190% and the amount of capital in that sector by a phenomenal 336%, according to figures reported by Anton Cheremukhin of the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas and co-authors. The Soviets, in other words, could move resources into the factories, but they could not maintain the efficiency with which they were used.

More importantly, the peasantry did not surrender “surplus” workers and grain without immense economic damage, bitter resistance and widespread suffering. Stalin expropriated, expelled or exterminated many of the most prosperous and sophisticated farmers (the “kulaks”), requisitioned grain at low prices and tried to nationalise draught-animals. In response, aggrieved farmers simply slaughtered their horses and oxen or stopped feeding them. These efforts to extract resources from agriculture by force were a disastrous blunder as well as a crime. At its worst, agricultural output declined by over a quarter compared with 1928, leaving the planners with less to redistribute to the urban workforce.

Growth without grotesquery

Could this violence and coercion be shorn from the Soviet approach as Nehru hoped? Mr Allen believes so: “The collectivisation of agriculture was not necessary for rapid growth,” he argues. Even Stalin eventually had to relent, requisitioning less grain, legalising private agricultural markets and permitting individual ownership of small plots of land.

Indeed, some economists believe that the broad outlines of the Soviet approach, minus the atrocities and the autarky, bear some resemblance to East Asia’s economic model. Paul Krugman, an American economist, made that comparison in 1994, arguing that the growth of the Asian tigers resulted from rapid accumulation of various kinds of capital, and not from the more efficient use of these resources. More recently, he has also argued that China’s high investment can be sustained only by the flow of surplus workers from overmanned farms. Now that China is “running out of peasants”, he warns, investment may collapse.

Mr Cheremukhin and his co-authors are more optimistic. Examining both China and the Soviet Union within the same analytical framework, they find notable differences. Most of China’s growth from 1978 to 2012 was because of increases in non-agricultural productivity, they find. And the migration of labour from field to factory was less important than the migration of resources from state-owned enterprises to private firms.

China may have exhausted its surplus peasantry, but the scope for reforming and retrenching its state-owned enterprises remains vast. The same is true of India. The Chhattisgarh steel plant set up with Russian help in 1955 is, for example, still going—part of India’s giant, publicly owned Steel Authority of India. But it is not a great advertisement for the Soviet approach. It has failed to meet Indian Railways’ requirement for new track. And its parent has lost money for nine quarters in a row.

——

Nov 9th 2017 | Finance and Economics | 1014 words