我听过不少关于比尔·佛吉博士的故事,这是我最喜欢的之一:有一天他到尼日利亚一个偏远的村落给村民接种天花疫苗,可当时大部分村民都在田间劳作。不过村长向他保证,说很快就会把所有人都召集起来。比尔起初不太相信,不过确实没过多久,村民们就聚集到了疫苗接种点。那天,比尔和他的助手给几千个村民接种了疫苗。比尔问村长是如何叫来这么多人的,村长回答说:“我叫大家来看全世界个子最高的人。”

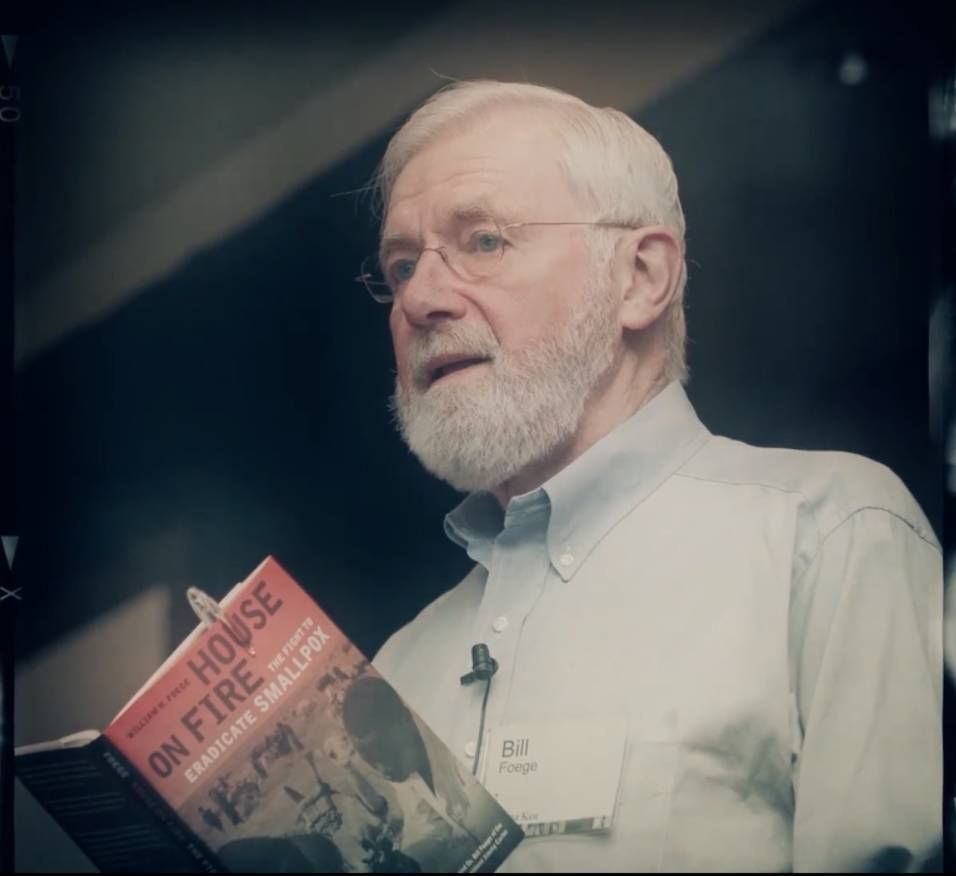

身高6英尺7英寸(约合201厘米),比尔的身材绝对算是高大。但他的名望可比他的身高要高多了。在过去60年里,他的智慧、领导力和谦逊的品德在与疾病与贫困的斗争中发挥了不可估量的作用。在全球健康领域,他是一个巨人。

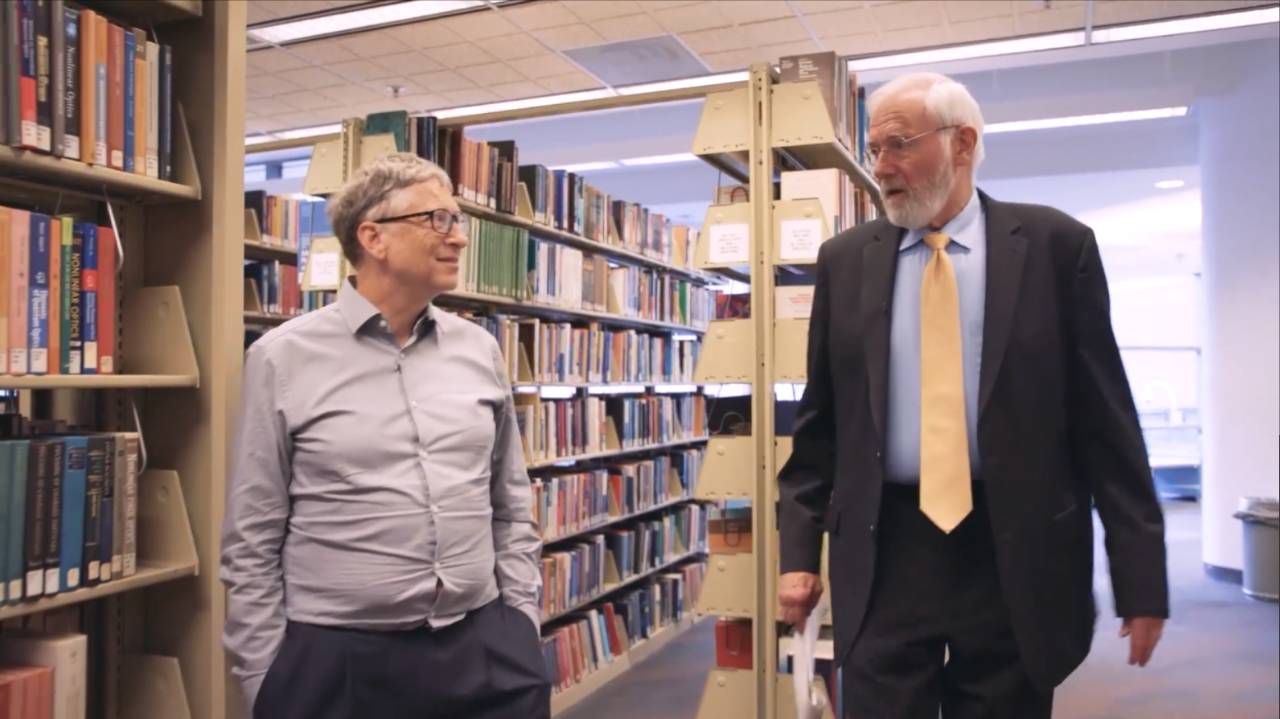

最近我和比尔有机会在亚特兰大相聚,我们谈到了天花,也谈到了他作为我与梅琳达导师的角色,以及全球健康领域令人惊叹的进展。

比尔最为人熟知的,是他曾在1960年代作为美国疾控中心流行病学家制定出的一项消灭天花的新策略。当时,消灭天花的策略依赖大规模免疫接种——为每一个人接种预防疾病的疫苗。然而发展中国家城市地区人口分布密集,要想实现为这些地区所有人接种疫苗是极为困难的。所以比尔想出了一个阻止天花病毒传播的新举措,那就是只给接触过病毒感染者的一小群人接种疫苗。这种名为“监测和围堵”的策略,使得卫生工作者能够在疫情爆发后及时做出响应,节省了大量的时间和金钱。这种新策略被广泛应用在非洲和印度,最终帮助在1980年正式消灭了天花。

(顺便提一下,40年前的这个月,索马里青年阿里·马欧·马阿林成为世界天然发生天花感染的最后一个人。不过他并没有将病传染给其他人,从而打破了天花病毒已经存在数千年的传播链。)

战胜天花的意义不仅是消灭了这个仅在20世纪就造成3亿人死亡的疾病,它还让全世界有信心继续开展根除其他疾病的工作,包括根除脊髓灰质炎的全球行动。

1984年,比尔主持建立了“儿童生存工作组”。在工作组的努力下,全球接受基础免疫接种的儿童比例翻了两番——从20%提高到接近80%。工作组现已更名为“全球健康工作组”,继续致力于应对影响全球最贫困人口的一系列健康议题,包括河盲症和其他被忽视的热带病。比尔还曾先后在美国疾控中心和卡特中心担任领导。

1999年,比尔加入我们的基金会担任高级顾问,帮助我们制定全球健康战略,这让我和梅琳达都激动不已。那时候,我仍然在微软公司全职工作,对全球健康领域所知甚少,但我迫不及待想要学习更多。

比尔成了我们的导师,不仅为我们答疑解惑,而且给我们上了一堂关于全球健康发展史的速成课。没有几个老师能像比尔这么有才。他旁征博引毫不费力,不论是伏尔泰和德谟克利特,还是《柳叶刀》杂志和世界卫生组织最新发布的论文及报告,他都信手拈来。对于世界在改善人类健康方面取得了多少成就,以及我们为减轻人类痛苦还能多做多少工作,他总是具有清晰的洞见。

比尔对帮助我们学习所做的最宝贵的事情之一,就是给了我们一份阅读清单,上面有关于全球健康议题的81本不同的书籍和报告,其中包括一本介绍天花的书(唐纳德·R·霍普金斯的《王子与农民——天花的历史》)、一本介绍疟疾历史的书(戈登·哈里森的《蚊子、疟疾和人:始自 1880 年的敌对史》)和一份关于全球健康投资重要性的开拓性报告(《1993 年世界发展报告:向健康投资》)。

所有这些书为我开启了一个崭新的世界,使得比尔对抗击贫困和疾病的热情也成为了我的热情。在我学习全球健康的过程中,我发现有个名字总是一再出现,它出现在抗击天花和脊髓灰质炎的故事里,也出现在消除麦地那龙线虫病和提高发展中国家医疗水平的故事里。那是比尔的名字。虽然比尔从不追求人们的关注,但他却在一项又一项改善全球最贫困人口健康状况的工作中留下了自己的印记。

回顾他成就卓著的一生,我把比尔看做粘合剂,他帮助让全球健康界紧密团结,将关注点聚焦在例如提高免疫覆盖的正确议题上,以及为我们看到全球健康在过去20年内取得的成就奠定了基础。

“发生这些事真的很不可思议。全球健康曾经如同一潭死水,任何人要想进入这个领域,只能摸着石头过河。”比尔这样对我说,“现在所有这些都变了。短短几年里,它成了一所接一所学校里最受欢迎的专业之一。”

跟随这位巨人的脚步,下一代公共卫生专业的学生能取得怎样的成就?我对此拭目以待。

Walking with a Giant

One of my favorite stories about Dr. Bill Foege is the day he arrived in a remote Nigerian village to vaccinate everyone against smallpox. Although most of the villagers were out working in the fields, the chief assured him he could quickly roundup everyone. Bill was doubtful, but soon people began flocking to the vaccination site. By the end of the day Bill and his team had vaccinated several thousand villagers. When Bill asked the chief how he got so many people to show up, the chief replied, “I told everyone to come and see the tallest man in the world.”

At 6 feet 7 inches, Bill is certainly tall in stature. But he stands even taller in reputation. His intelligence, leadership, and humility over the last six decades have proven invaluable in the fight against disease and poverty. In the field of global health, he is a giant.

Bill and I recently had a chance to catch up in Atlanta, where we talked about smallpox, his role as a mentor for Melinda and me, and the stunning progress being made in global health.

Bill is best known for devising a new strategy for eradicating smallpox as an epidemiologist working for the Centers for Disease Control in the 1960s. At the time, the eradication strategy relied on mass vaccination—vaccinating everyone against the disease—but trying to reach the entire population in densely populated urban areas of the developing world proved very difficult. So Bill developed a new approach to stop the virus from spreading by vaccinating a limited number of people—only people who had been exposed to people who were infected. The strategy—which became known as “surveillance and containment”—allowed health workers to respond quickly to outbreaks and saved time and money. This new approach was employed across Africa and India, leading to the official eradication of smallpox in 1980.

(Incidentally, this month marks 40 years since a young man in Somalia named Ali Maow Maalincontracted the world's last case of naturally occurring smallpox. By not passing the disease to any other person, he broke the chain of transmission that had existed for thousands of years.)

The defeat of smallpox did more than bring an end to a disease that killed 300 million people in the 20th century alone. It gave the world the confidence to take on the other eradication efforts, including the global effort to wipe out polio.

In 1984, Bill was instrumental in launching the Task Force for Child Survival, which quadrupled—from 20 percent to almost 80 percent—the proportion of children around the world who receive basic vaccinations. Now known as the Task Force for Global Health, the organization continues to work on a range of health issues affecting the world’s poorest, including river blindness and other neglected tropical diseases. Bill also took on leadership roles as director of the Centers for Disease Control and later director of the Carter Center.

In 1999, Melinda and I were thrilled when Bill joined the foundation as a senior advisor to help us develop a global health strategy. At the time, I was still working full time at Microsoft and I knew very little about global health, but I was eager to learn.

Bill served as our mentor, answering our questions and giving us a crash course in the history of global health. There are few teachers as talented as Bill. As comfortable quoting Voltaire and Democritus as the latest Lancet article or World Health Organization report, Bill is always clear in his thinking about how much the world has accomplished in improving health, as well as how much more we can do to alleviate human suffering.

One of the most valuable contributions Bill made to our learning was giving us a reading list with 81 different books and reports on global health issues. Among them, a book on smallpox (Princes and Peasants – Smallpox in History by Donald R. Hopkins), the history of malaria (Mosquitoes, Malaria & Man: A History of the Hostilities Since 1880 by Gordon Harrison), and a groundbreaking report on the importance of global health investment (Investing in Health: World Development Report 1993).

All these books opened a new world for me, making Bill’s passion for fighting poverty and disease a passion of my own. As l learned more about global health, I discovered that one name appears again and again in accounts about the fights against smallpox and polio to campaigns to wipe out Guinea Worm and improve health care in the developing world. It is Bill’s. While never eager to take the limelight, Bill left his mark on one effort after the next to improve the health of the world’s poorest people.

Looking back at his lifetime of achievements, I view Bill as the glue that held the global health community together, getting it to focus on the right priorities, like raising the immunization coverage, and setting the stage for the progress we’ve seen in global health over the last 20 years.

“It is incredible what has happened. We’ve gone from global health being a total backwater of study. Anyone who wanted to get into it had to discover their own way,” Bill told me. “All that changed and within a few short years it turned out to be one of the most popular subjects in school after school.”

I look forward to seeing what the next generation of public health students will accomplish—by following in this giant’s footsteps.