安进诉赛诺菲案的口头辩论表明,最高法院的一项重大裁决可能会进一步减损功能索赔限制(所有这些都是属索赔)。关键问题是,法院是否会限制主要影响“

unpredictable arts.

”

在辩论中,最高法院对专利权人律师Jeffrey Lamken及其为安进公司功能声称的抗体属辩护的企图相当

hostile

。

密苏里大学法学院法学教授Dennis Crouch

认为Lamken犯了错误,他首先反复告诉法庭,这一说法只涵盖了大约400种抗体,然后最终承认,这一范围涵盖了数百万种尚未确定的抗体。法院的几名成员对明确的功能性索赔限制比较

struggle

,该限制允许安进公司索赔所有达到其声明结果的抗体。Lamken建议“PTO定期发布具有这种功能的专利。”当然,PTO也定期发布无效和过度授权的专利。在质询中,法院显然认为由于功能限制,存在潜在的资格问题。Paul Clement在回应中谈到了这个问题,并解释说,功能)的说法是“Myriad的一个变通方案。因为基本上他们指的是自然界中存在的东西(PCSK9途径),他们说,

we claim everything that works to bind there en bloc

。”

在安进诉赛诺菲案中,最高法院同意重新评估联邦巡回法院适用的启用原则。尽管陪审团两次站在专利权人一边,但地区法院和上诉法院都驳回了陪审团的裁决,并得出结论,从法律角度来看,缺乏授权披露。联邦巡回法院特别指出(1)功能限制比结构限制更难实现,(2)属权利要求所涵盖的每个实施例都必须实现。在这里,法院指出,安进未能实现“

far corners of the claimed landscape

”。

安进已要求法院在启用测试中纳入一项有意义的限制。在该框架中,专利挑战者将需要证明(1)一些实施例需要不适当的实验才能重新创建,以及(2)这些失败对熟练的技术人员来说是有意义的。而且,安进建议功能属不应该面临更严格的审查。最后,安进建议应该减少

Wands Factors

的权重——今天它们被用作测试,而不是功能支持。专利权人面临的特殊Wands问题是抗体是“不可预测的”,因此需要更多的披露。

这种情况非常严重,不仅仅是针对抗体。每一项权利要求都涵盖了无数未公开的实施例;每个都在使用很多功能限制;每一项专利都会遭遇 unenabled far corners。

The claim here:

-

An isolated monoclonal antibody, wherein, when bound to PCSK9, the monoclonal antibody binds to at least one of the following residues: S153 … or S381 of SEQ ID NO:3, and wherein the monoclonal antibody blocks binding of PCSK9 to LDLR.

安进的发明围绕着其他人发现的一种途径展开,该途径涉及低密度脂蛋白,又名“坏胆固醇”,肝脏在破坏坏胆固醇中的作用,以及一种新的蛋白质PCSK9。肝脏有低密度脂蛋白受体(LDLR),可以结合并分解低密度脂素。但是,身体也会产生一种名为PCSK9的蛋白质,该蛋白质与这些受体竞争性结合,并阻断肝脏低密度脂蛋白的分解作用。在这项发明专利中,安进筛选了与PCSK9结合并阻断其功能的单克隆抗体,从而使肝脏能够分解低密度脂蛋白。过程比较简单,首先给人源化小鼠进行PCSK9免疫,以产生了一系列与PCSK9结合的抗体(约3000个),然后对所有抗体进行测试筛选以确定哪些抗体与PCSK9的功能表位结合,从而产生“阻断PCSK9与LDLR的结合”的影响。这一过程使其减少到约400个抗体。然而,安进实际获得了其中16抗体序列,而赛诺菲的产品很可能是安进公司发现的400个抗体之一(。。。),但安进公司的专利中并没有具体描述。相反,安进描述了这个过程,还描述了使用密码子替换过程来检查类似的抗体。

Clement的一句关键名言是:“我认为功能属权利要求很糟糕。”他的论点的本质是,它们有可能给专利权人一个广泛的范围,涵盖许多截然不同的解决方案。然而,结果是由于涉及专利,

nobody has incentives to look for the others because of the covering patent

。“他们阻碍了科学的发展。”在他看来,更有限的垄断要好得多——“

We’re better off with two competing independently developed therapies

。”

Colleen Sinzdak代表美国政府辩护,而不是作为法庭之友,并支持赛诺菲。Sinzdak完全同意Clement的观点,认为广泛的属主张是“对创新的危险,尤其是在医学领域。”

政府认为,只有在属内的每一个具体实施方案都已启用的情况下,属主张才是正确的。“真的就这么简单……你真的需要启用你所声称的每一种不同的实施方式。”Sinzdak认为,在一个不可预测、快速发展的领域,法律应该更加严格,以允许早期专利过度抢占土地并停止进一步的研究。Sinzdak建议法院强制执行狭义的索赔,然后在必要时让人们依赖对等原则。

Lamkin的重要反驳点是:尽管安进并没有真正公开每一种实施方案,而且一些涵盖的实施方案在结构上与公开的实施方案完全不同,但“

the key fact in this case is that Sanofi has not identified one antibody that would require undue experimentation to make

。”

About the case

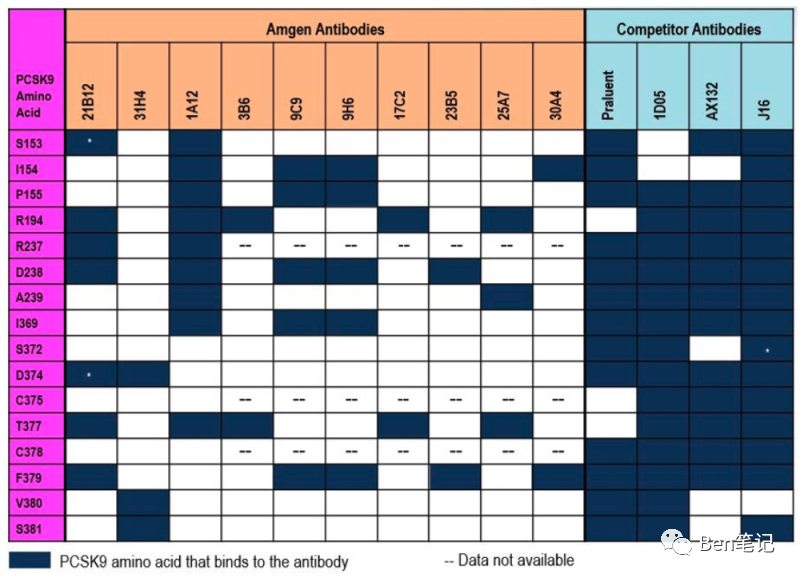

The claims at issue in Amgen's asserted patents, U.S. Patent Nos. 8,829,165 ("'165 patent") and 8,859,741 ("'741 patent"), encompassed antibodies that recognized specific amino acids in the amino acid sequence of the PCSK9 protein, reciting no structural features or limitations of these antibodies but rather the combination of "target" amino acids, as illustrated in Amgen's brief:

Sanofi's brief begins with an appropriate amount of advocacy, admirably avoiding purple prose in describing their response to Amgen's assertions in its Opening Brief, stating that Amgen's filing of the patent at issue was strategically aimed at preventing Sanofi from marketing its PCSK9 antibody Praluent® (alirocumab) "in a blatant attempt to corner the market" by claiming a genus of antibodies by function rather than structure (noting that its patent claimed its Praluent antibody by its amino acid structure), and then "asserting a monopoly over an entire genus of functionally defined claims." In so doing, Sanofi argues Amgen created the "high hurdles" Amgen accuses the Federal Circuit of raising by attempting to contravene the "commonsense proposition" that "the more companies claim as their patent monopoly, the more they must enable" which is "the heart of the patent bargain." Regarding the disclosure Amgen relies upon in ts specification, the brief asserts that it merely tells the skilled artisan "to make claimed antibodies by randomly generating and testing candidates via processes well-established in the prior art." The brief illustrates the scope of Amgen's claims with regard to four antibodies made by Amgen's competitors (including Praluent) and how different they were from the antibodies actually disclosed in Amgen's specification:

Regarding the policy consequences attendant upon Amgen's position the brief states that:

The simple reality is that Amgen has claimed a monopoly over far more than it has enabled. Such claims are not just invalid, but dangerous. They can take medicines away from physicians and patients and could allow someone without a clinically valid species to claim an entire genus of medically-vital antibodies they have not yet discovered.

The brief also emphasizes the health risks of LDL-C and attendant importance of Praluent in addressing this risk (which Amgen's patent threatens) and that the matter before the Court does not involve Amgen's patent on Repatha® itself, countering Amgen's arguments in its brief that it had invested "billions of dollars and a decade of research bringing [it] to market" as a reason to overturn the Federal Circuit's decision.

On the law Sanofi argues that the Federal Circuit's straightforward application of the enablement standard applying the

Wands

factors was entirely consistent with the history of the statute and judicial interpretations thereof, including importantly Supreme Court precedent. This standard "has long been understood to require sufficient disclosure to enable a skilled artisan to make the entire invention claimed, not just a subset, without the need for any significant independent experimentation" under that precedent. The brief characterizes as a "straw man" Amgen's argument in its Opening Brief that the Federal Circuit has established a new, unnecessarily stringent test for enablement.*

The Argument section of the brief assays the precedential history of the Supreme Court's and lower courts' upholding the conventional enablement standard and its relationship to the patent bargain, wherein the scope of enabled claims is determined and cabined by what is disclosed, citing

Pennock v. Dialogue

, 27 U.S.1, 23 (1829) (Story, J.);

J.E.M. Ag Supply, Inc. v. Pioneer Hi-Bred Int'l, Inc

., 534 U.S. 124, 142 (2001);

Festo Corp. v. Shoketsu Kinzoku Kogyo Kabushiki Co

., 535 U.S. 722, 736 (2002), and precedents under English law,

King v. Arkwri

ght, (K.B. 1785). The brief draws parallels regarding this understanding of what is required to satisfy enablement under English law to enactment of the first Patent Act in 1790 and the consistency of this standard in subsequent patent law enactments. This interpretation of the enablement statute is supported in the brief by a thorough explication of judicial precedent consistent with Sanofi's argument that scope requiring undue experimentation has historically been deemed inadequate, including

Consol. Elec. Light Co. v. McKeesport Light Co. (The Incandescent Lamp Patent)

, 159 U.S. 465, 474-75 (1895) ("painstaking experimentation";

Holland Furniture Co. v. Perkins Glue Co

., 277 U.S. 245, 256-57 (1928) ("elaborate experimentation"), and finally the modern "undue experimentation" standard adopted by the CCPA in

In re Folkers

, 344 F.2d 970, 976 (C.C.P.A. 1965), and adopted by the Federal Circuit in

In re Wands

, 858 F.2d 731 (Fed. Cir. 1988) (reciting the

Wands

factors).

The brief then sets forth the recent history of cases illustrating how the Federal Circuit (consistent with this precedent) has held cases to be non-enabled "if a claim encompasses 'thousands' of 'candidate compounds,' and 'testing' or 'screening' of each candidate is necessary 'to determine which . . . meet [the] claim,'" citing

Idenix Pharms. LLC v. Gilead Scis. Inc.

, 941 F.3d 1149, 1156-58, 1162-63 (Fed. Cir. 2019);

Enzo Life Scis., Inc. v. Roche Molecular Sys., Inc

., 928 F.3d 1340, 1345-49 (Fed. Cir. 2019);

Wyeth & Cordis Corp. v. Abbott Labs

., 720 F.3d 1380, 1384-86 (Fed. Cir. 2013), characterizing these decisions as "guard[ing] against what Amgen has done here: claim a lot and disclose a little, such that skilled artisans (and even Amgen's own scientists) must engage in undue experimentation because the disclosure leaves them guessing as to how to make and use the full scope of the claimed invention."** This is not a "special rule" for functional genus claims, the brief argues but rather a consequence of "some genus claims assert a monopoly over far more than they enable," contrary to both the statute and precedent.

Turning to a direct confrontation of Amgen's arguments in its Opening Brief, Sanofi contends that Amgen has provided the Court with no persuasive reasoning for changing the established standard (under which Sanofi contends the District Court and Federal Circuit properly invalidated Amgen's claims on enablement grounds). As characterized by the brief, Amgen itself has not challenged the conventional test (or otherwise would have had to argue contrary to its own arguments below). Rather, the brief argues, Amgen has created, by a "profound mischaracterization" of the decisions below, a chimerical "new" and "different" enablement standard, the "full-scope" requirement, that Sanofi argues is not what the Federal Circuit held, citing language from that Court's decision expressly disclaiming such a standard (the decision "specifically resisted what might be termed a simple 'numerosity' or 'exhaustion' requirement," and that any assertion that the Federal Circuit had "adopted a 'numbers-based standard' to evaluate enablement" that asked "how long it would take to make and screen every species" simply "mischaracterizes our law"). In the Federal Circuit's view (as explained in the brief) "[t]he problem was that the unpredictability of the science combined with a broad functional claim that 'extend[ed] far beyond the examples and guidance provided' left skilled artisans with no ability to generate specific undisclosed embodiments and no option but to engage in trial and error using well-established techniques to generate candidate antibodies that would then still need to be tested to ascertain whether they came within the claimed genus." And Amgen nowhere has identified language in the Federal Circuit's opinion reciting its "new standard" according to the brief. The important distinction made in the brief between what the Federal Circuit held and what Amgen asserts its decision means is:

When a specification enables a skilled artisan to predictably make specific undisclosed embodiments under circumstances where making all of them would take time, the cumulative effort needed to make and use every single embodiment of the claimed invention is unproblematic. But when the specification provides no useful guidance to skilled artisans to make and use specific undisclosed embodiments and consigns them to a trial-and-error process to unpredictably generate antibodies that must then be tested to determine whether they even fall within the broad functionally claimed genus, Federal Circuit precedent along with this Court's precedent and statutory text all indicate that the claimed invention is not enabled.

This does not constitute a new test according to the brief, contrasting the situation with the patents before the Court with Amgen's and Sanofi's patents on their Repatha and Praluent antibodies, respectively, which provide an unchallenged enabling disclosure of the amino acid sequence of these antibodies.

The brief also argues that the Court should reject Amgen's "as-needed" enablement test advocated as an alternative, based on its inconsistency with the "statutory text, settled precedent, or longstanding practice," providing extensive analysis of precedent and the history of enablement law in support of its position.

The brief then sets forth Sanofi's arguments that, contrary to Amgen's assertions it is Amgen's position(s) that threaten to harm innovation, by permitting Amgen (and applicants in Amgen's position in future) to patent protection for claims outside what has been disclosed and thus precluding others from their inventions that

have

been enabled. Under current Federal Circuit precedent, innovation has not been harmed according to the brief (disregarding the one non-precedential decision by the PTAB cited in Amgen's Opening Brief, which was based on conventional application of the

Wands

factors). The brief also cites several instances where the Federal Circuit and district courts have upheld satisfaction of the enablement requirement in biotech and pharma cases, specifically

Bayer Healthcare LLC v. Baxalta Inc

., 989 F.3d 964, 970-71, 980-81 (Fed. Cir. 2021), and

Erfindergemeinschaft UroPep GbR v. Eli Lilly & Co

., 276 F.Supp.3d 629, 659-663 (E.D. Tex. 2017), and noting that innovation in these areas has proceeded without enablement impediment in these industries (citing paradoxically Prof. Karshtedt's law review article in support of this argument). The brief cites the doctrine of equivalents to counter Amgen's arguments against the threat of mere copyists if genus claims of broad scope are precluded by the enablement requirement, and the countervailing risk to innovation Sanofi asserts is raised by claims having Amgen's scope. The brief argues that this case "perfectly illustrates the risks" wherein Amgen's patents if upheld would ban Sanofi's Praluent from the marketplace and prevent patients needing it from getting it, particularly to the extent that Praluent is available in dosages Amgen cannot provide ("allowing a company that has discovered only particular species to obtain a patent on a broad functionally claimed genus creates a very real risk that important medical treatments will never reach the market"). The brief uses the history of Pfizer's unsuccessful attempts to gain regulatory approval for its anti-PCSK9 antibody as a "cautionary tale," where if Pfizer had adopted the claiming strategy followed by Amgen "it would have stifled innovation, and patients would have had no PCSK9 antibody therapies at all—or, at best, would have had to wait longer for Pfizer to develop a safe and effective antibody through trial and error."

Finally, Sanofi's brief sets forth specifically why Amgen's specification is not enabling for the scope of the functionally defined genus claims at issue before the Court, why Sanofi agrees that the case "does not require a third trip through the Federal Circuit" and that the decisions below should be affirmed.

There are a plethora of

amicus

briefs on both sides of the issue in this case, and those briefs will be the subject of future posts. The Supreme Court should render its decision by the end of the current term.

* In this regard the brief distinguishes Professor Dmitry Karshtedt's law review article on "The Death of the Genus Claim" by stating even those authorities ultimately concede that innovation has not been harmed by the decision.

** What these cases arguably do is remove the conventional application of the

Wands

standard that extensive experimentation is not undue if it is routine such that the extensiveness of the experimentation can itself be undue and thus non-enabled (despite the Federal Circuit's assertions to the contrary)

资料来源:

Patent Docs: Sanofi and Regeneron File Respondents' Brief on Amgen v. Sanofi