中文导读

随着女性地位的提高,日本工作女性的人数逐年上涨,但是在各行各业中坐上较高职位的女性却是凤毛麟角。背后的原因则与日本的工作文化密切相关。工作时间、抚育孩子、料理家务、照看老人等都给女性在职业上的突破造成巨大困难。虽然近年来由于经济的驱动,此种情况正在改善,但更大的进步还依赖于国家更多赋予女性权利和社会价值观的进一步改变。

Women are working more, but few are getting ahead

WHEN Kanako Kitano was job-hunting, she looked for a company that would not treat her differently because she is female. “The companies talked about how they gave the same opportunities to men and women,” the 21-year-old says. “But at the career fair they had men doing the talking surrounded by a bunch of women handing out leaflets.” She eventually opted for a job at Bloomberg, an American media company.

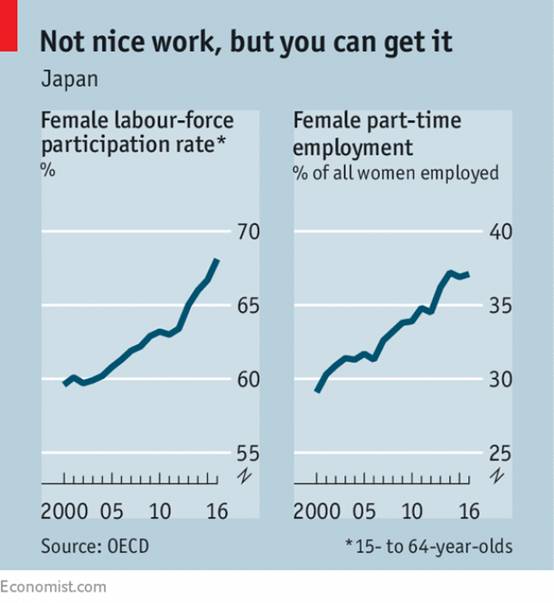

By and large, women in Japan work: 68% of those aged 15 to 64 are employed or looking for a job, a similar figure to America. The chart of the proportion of women in work by age is still “m-shaped”, as women drop out of work when they marry or have kids before returning later on. But the decline in the middle is now more of a dip than a valley. Today just over half of women continue working after their first child is born, compared with 38% in 2011.

Office culture is slowly changing, too. Gone are the days when female workers were only hired as lowly administrators or unabashedly referred to as “office flowers”. Few now think like Kazuyo Sejima, a renowned architect, who forswore children when she started out in the 1970s because she never imagined that she could have both a fulfilling career and a family.

Shinzo Abe, the prime minister, has sworn to boost women’s economic opportunities as a way to revive the economy. The advancing participation rate suggests his effort to “make women shine” is having some success. But huge problems remain. “The limitlessness of Japan’s working culture—in terms of the hours, giving everything you have and being expected to move at the whim of the company—is the biggest obstacle,” says Kimie Iwata, who sits on the board of Japan Airlines and heads the Japan Institute for Women’s Empowerment and Diversity Management.

The government estimates that 2.7m women want to work, but do not. Caring for children or elderly parents often pulls them away from the office. A shortage of nursery places is a particular gripe. But more often women cite factors pushing them out of the workplace, such as

mata hara

, harassment for getting pregnant or taking maternity leave. Women are disproportionately in part-time or casual work (see chart)—with worse pay, worse benefits and worse career prospects. They earn 74% of the median male wage on average, compared with 81% in America.

The disparity is especially stark at the highest ranks. Only two of Japan’s 20 cabinet ministers are women. A woman cannot head the imperial family. No company on the Nikkei index has a female boss, an even poorer showing than the paltry seven on Britain’s FTSE 100.

Keiko Takegawa, who heads the government’s gender-equality bureau, says that by some measures Japan fares worse than Arab countries. Only 10% of lawmakers are women, compared with 27% in Iraq. Only 15% of scientific researchers are female, compared with 25% in Libya. “We lack role models,” says Kaori Fujiwara of Calbee, a snack-food company known for promoting women.

Since Mr Abe came to office in 2012, he has created more nursery places and, in last month’s general election, promised free child care. Since last year big companies have been required by law to document their efforts to promote women. A few firms now allow remote working or more flexible hours.

But, both for Mr Abe and for society as a whole, there is a sense that economic imperatives, rather than evolving cultural attitudes, are prompting these changes. Many members of Mr Abe’s Liberal Democratic Party see putting women to work as a lesser evil than accepting mass immigration, and thus as the only way to counter a shrinking working-age population. The erosion of the old unwritten guarantee of a job for life for employees of big firms has led more men to say they want their wives to work; women, too, cite money as a consideration. What is missing, says Kumiko Nemoto of Kyoto University of Foreign Studies, who has written a book on working women, “is any discussion about the value of equality in and of itself”.

The media continue to convey a “super feminine” ideal of womanhood, says Ms Nemoto. Magazines discuss how women can improve their

joshi-ryoku

. This is often translated as “girl power”, but applies to a woman who can cook, sew and make impressive

bento

(lunch) boxes. Even Mr Abe’s catchphrase about letting women “shine” has a condescending ring.

Career women do not get much help at home. In households where both partners work, men spent 46 minutes a day on domestic tasks compared with almost five hours for women, a far lower share than American men. Agony columns and online forums are full of women grumbling about being wan ope

ikuji

(solo childcare), an adaptation of a phrase originally coined to refer to convenience-store employees who were left to mind the shop on their own. Only 3.1% of men take their (relatively generous) statutory year’s paternity leave, with low uptake even in workplaces where it is culturally accepted, such as Ochanomizu University, a women’s institution in Tokyo.

Some women do not mind all this. “I feel sorry for my brother. I have choices on how to be successful whereas for men work is the only way,” says 20-year-old Hinano Sukeda. Some older career women accuse their younger peers of lacking ambition and preferring to be kept. Ms Kitano admits, “I feel we should speak out more, but there is a culture of just fitting in.”

——

Nov 16th 2017 | Asia | 919 words