There has never been a more exciting pharmaceutical era in China, with the R&D emphasis shifting

from generic to innovative drugs. Oncology has been atthe forefront ofthis transition. Indeed,

12

out of

44

of the

new cancer drugs approved in China in between 2018 and August 2020

were

discovered in China. Although most were me-too drugs from established drug classes, first-in-class

candidates are also emerging.

Here, we overview the landscape of domestic oncology drug pipelines in China, with the aim of

providing insights on the evolution ofthe pharmaceutical ecosystem and R&D trends. For details

ofthe data and analysis as well as additional figures, see the Supplementary Information.

From me-too to first-in-class

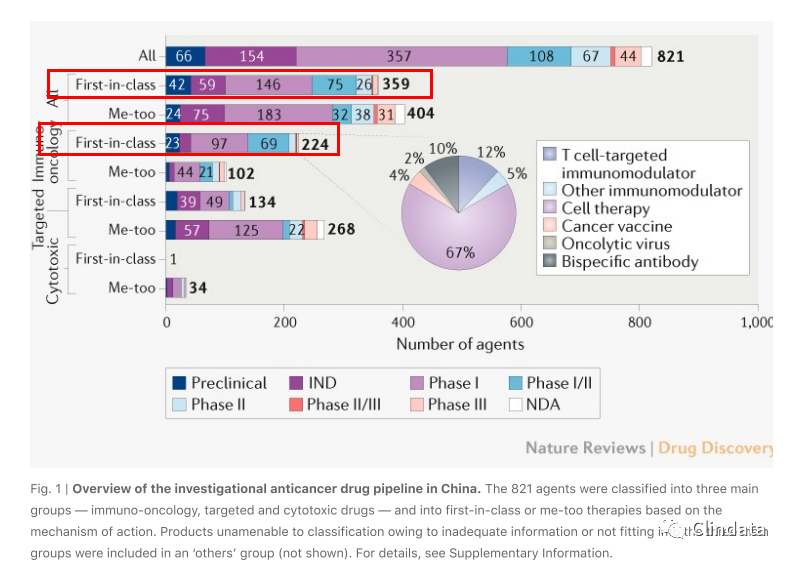

As ofJanuary 2020,there were 821 investigational anticancer drug candidates in China, including

404 me-too and 359 first-in-class agents (Fig. 1).

Fresh from the transition from generics, many start-up companies have opted for less risky and

potentially faster paths towards commercial viability by developing me-too drugs, in some cases

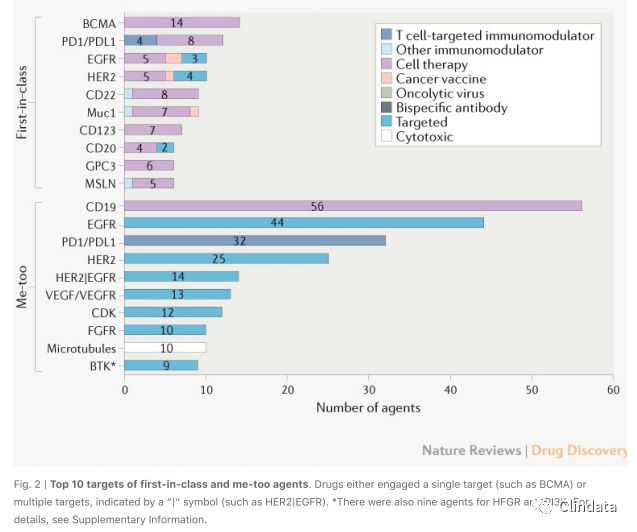

following closely behind the pioneering therapies such as celltherapies. The largest groups among

the me-too drugs were 56 CD19-directed chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T celltherapies, 83

targeted therapies against EGFR or HER2 and 32 monoclonal antibodies targeting PD1 or PDL1 (Fig.

2).

Moderate market competition may increase availability and affordability for patients, but

developers who focus only on me-too drugs risk using resources less efficiently and hampering

long-term innovation. As the market becomes more established and self-regulated, limited market

shares in the context of a highly competitive environmentfor similar drugs may reduce the

attractiveness of me-too candidates. Aims of government policy, such as reduced profit margins

due to health insurance reforms and future requests by regulatory authorities to demonstrate

superiority in trials against active controls before marketing approvals may further promote the

development of drugs with best-in-class potential. In this respect,the EGFR inhibitor almonertinib

and the BTK inhibitor zanubrutinib are successful recent examples.

Cutting-edge scientific discoveries and technological revolution in China generally stem from

academia, as indicated by a higher proportion of first-in-class oncology agents developed by

academia than by industry (80% versus 40%; Supplementary Fig. 1). Further translation into

products and commercialization requires participation from industry. The pioneering

development of glypican 3 (GPC3)-directed CAR T cells (GPC3-CART) provides one illustration of

collaboration between academia and industry.

Looking atthe first-in-class pipeline,there are a substantial number of candidates in the immunooncology (IO) field. Celltherapies are particularly prominent, making up 150 out ofthe 224 first-inclass IO agents (67%, Fig. 1, Supplementary Fig. 2). Celltherapies also dominate the top 10 targets

for first-in-class agents, such as BCMA, CD22, mucin 1, CD123 and GPC3 (Fig. 2; Supplementary

Table 1). This level ofinnovation is reflected in China’s position in the global celltherapy pipeline,

second only to the United States in terms ofthe number of agents in development(Nat. Rev. Drug

Discov. 19, 583–584; 2020). This has been stimulated by the government’s prioritization and

regulatory reforms. Since December 2017, China has reconfigured the landscape for celltherapy

development, by incorporating itinto the Thirteenth Five-Year Plan and issuing technical

guidance.

Newer technologies are also offering possibilities of pursuing established single or multiple targets

in a novel way (Fig. 2; Supplementary Fig. 3). Examples include celltherapies targeting PD1/PDL1,

EGFR and HER2, HER2-based bispecific antibodies and CD19-based bispecific celltherapies. Multitargeted drugs may offer transformative potential, given that combination treatmentis already a

cornerstone of cancer therapy.

Unmet needs drive innovation

In the overall pipeline, 495 products are being developed for solid tumours, with targeted

therapies making up the largest group (62%, Supplementary Fig. 4). Despite the major challenges

in tackling solid tumours with celltherapies,there are also 83 celltherapies for such tumours in

development. Celltherapies make up around half(51%) ofthe 249 products being developed for

haematologicaltumours. Frequenttargets include the established target CD19, as well as the firstin-class targets CD22 and BCMA.

Using disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), a measure of disease burden incorporating morbidity,

mortality and disability,to approximately reflect unmet medical needs, our analysis indicated a

strong correlation between the number of drugs and the corresponding disease burden in China

across 23 solid tumours and 7 haematological cancers (Supplementary Fig. 5). With the highest

DALY burden in China, lung cancer had the greatest number of candidate drugs,the majority of

which were me-too drugs. For some cancers with a high DALY burden in China, such as esophageal,

gastric and hepatic cancer,the numbers of candidate drugs were lower than might be expected on

the basis of a linear correlation, butthe proportions that were first-in-class were relatively higher

(Supplementary Fig. 4 and 5), atleast partially owing to the lack of validated targets for these

cancers.

Innovation in and out

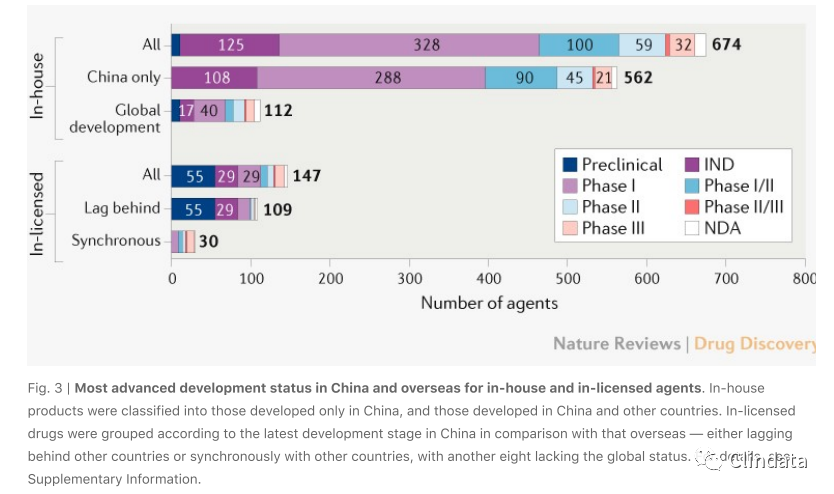

China has now become a major target country for R&D globalization. One way to penetrate China

for overseas developers, especially biotech companies, is through in-licensing to Chinese

biopharma companies. In early 2020,the proportion ofin-licensed candidates in the overall

pipeline rose to 18% (147),transferred primarily in preclinical or early clinical phases (Fig. 3).

Typical development paths initially focused on niche indications or advanced tumours, which may

shorten the time to reach the Chinese market. For example, niraparib was licensed to Zai Lab by

Tesaro in 2016 and granted marketing approvalfor recurrent ovarian cancer in China in 2019.

Notably, 30 investigational products were at concurrent stages in and outside China (Fig. 3),

highlighting China’s openness towards accepting foreign data.

Products discovered in China are also being developed outside the country (112 out of 674 agents;

(Fig. 3)), indicating the external recognition of Chinese discovery capabilities, manufacturing

quality and study design. In particular, 17 agents were out-licensed to companies externally. For

example,the BCMA-directed CAR T celltherapy LCAR-B38M, which has received breakthrough

therapy designation in the United States and China, was licensed by Janssen Biotech from Legend

Biotech in 2017.

Outlook

Although the oncology pipeline in China is being driven by the unmet medical needs,the

innovation could be compromised by inappropriate trial design and excessive expenditure but

insufficient rewards. Future oncology trials will need to adaptto innovative, integrative platforms

to test multiple candidates in designated patient populations using resource-optimized and costefficient approaches. If China continues to develop an environmentthat encourages innovation

and the regulatory agency keeps an open mind about noveltechnologies and products,the

emergence of a cluster of home-grown, ground-breaking therapies can be anticipated,through

collaboration between academia and industry in China and beyond.