中文导读

在中国,凌晨四点在医院门口排着长队已经是司空见惯的现象了,尤其是在北京上海等地。基层医疗人员的低收入,让许多医学生选择去医院工作;基层医疗设施的不完善,又增加了群众对基层医疗的不信任。这导致了本就紧缺的医疗资源不能最大限度合理使用,医生和患者都备受煎熬。同时,老龄化又是另一根压在这上面的稻草,基础医疗这头“骆驼”想要很好地承担起运送的职责,尚需时日。

China is trying to rebuild its shattered primary health-care system. Patients and doctors are putting up resistance.

QUEUES at Chinese hospitals are legendary. The acutely sick jostle with the elderly and frail even before gates open, desperate for a coveted appointment to see a doctor. Scalpers hawk waiting tickets to those rich or desperate enough to jump the line. The ordeal that patients often endure is partly the result of a shortage of staff and medical facilities. But it is also due to a bigger problem. Many people who seek medical help in China bypass general practitioners and go straight to hospital-based specialists. In a country once famed for its readily accessible “barefoot doctors”, primary care is in tatters.

Even in its heyday under Mao Zedong, such care was rudimentary—the barefoot variety were not doctors at all, just farmers with a modicum of training. Economic reforms launched in the late 1970s caused the system to collapse. Money dried up for rural services. In the cities, many state-owned enterprises were closed, and with them the medical services on which urban residents often relied for basic treatment. It was not until 2009, amid rising public anger over the soaring cost of seeing a doctor and the difficulty of arranging consultations, that the government began sweeping reforms. Goals included making health care cheaper for patients, and reviving local clinics as their first port of call.

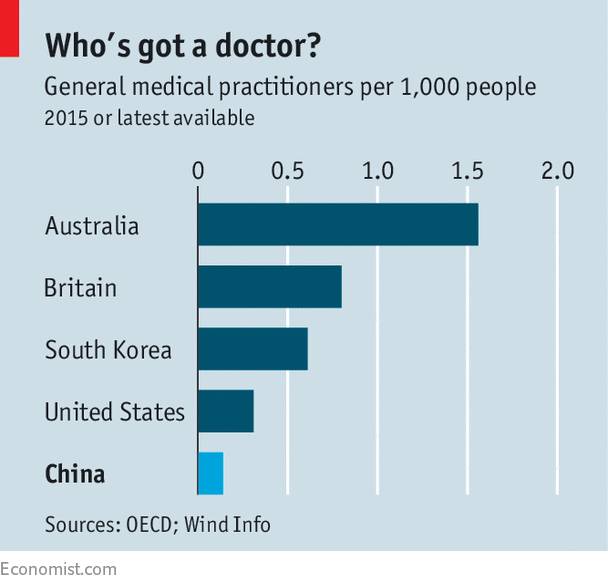

The reforms succeeded in boosting the amount that patients could claim on their medical-insurance policies (some 95% of Chinese are enrolled in government-subsidised schemes). They have also resulted in greater funding for community health centres. In 2015 there were around 189,000 general practitioners (GPs). The government aims to have 300,000 by 2020. But there would still be only 0.2 family doctors for every 1,000 people (compared with 0.14 today—see chart). That is far fewer than in many Western countries.

It is not just long waiting-times at hospitals that necessitate more clinics. People are living far longer now than they did when the Communists took over in 1949: life expectancy at birth is 76 today, compared with 36 then. People from Shanghai live as long as the average person in Japan and Switzerland. Since 1991, maternal mortality has fallen by over 70%. A growing share of medical cases involve chronic conditions rather than acute illnesses or injuries. GPs are often better able to provide basic and regular treatment for chronic ailments. The country is also ageing rapidly. By 2030 nearly a quarter of the population will be aged 60 or over, compared with less than one-seventh today. More family doctors will be needed to manage their routine needs and visit the housebound.

But setting up a GP system is proving a huge challenge, for two main reasons. The first is the way the health-care system works financially. Hospitals and clinics rely heavily on revenue they generate from patients through markups on medicine and other treatments. The government has curbed a once-common practice of overcharging patients for medicines. But doctors still commission needless scans and other tests in order to make more money.

Community health centres are unable to offer the range of cash-generating treatments that are available at hospitals. So they struggle to make enough money to attract and retain good staff. Most medical students prefer jobs in hospitals, where a doctor earns about 80,000 yuan ($11,600) a year on average—a paltry sum for someone so qualified, but better than the 50,000 yuan earned by the average GP. Hospital doctors have far more opportunities to earn substantial kickbacks—try seeing a good specialist in China without offering a fat “red envelope”.

As a result, many of those who train as GPs never work as one. Most medical degrees do not even bother teaching general practice. That leaves 650m Chinese without access to a GP, reckon Dan Wu and Tai Pong Lam of the University of Hong Kong. The shortage is particularly acute in poor and rural areas. The number of family doctors per 1,000 people is nearly twice as high on the wealthy coast as it is in western and central China.

The second main difficulty is that many ordinary Chinese are disdainful of primary-care facilities, even those with fully qualified GPs. This is partly because GPs are not authorised to prescribe as wide a range of drugs as hospitals can, so patients prefer to go straight to what they regard as the best source. There is also a deep mistrust of local clinics. The facilities often lack fully qualified physicians, reminding many people of barefoot-doctor days. Chinese prefer to see university-educated experts in facilities with all the mod cons.

Patients have few financial incentives to consult GPs. Even those who have insurance still have to meet 30-40% of their outpatient costs with their own money. Many prefer to pay for a single appointment with a specialist rather than see a GP and risk being referred to a second person, doubling their expenditure. Since the cost of hospital appointments and procedures is similar to charges levied at community centres, seeing a GP offers little price advantage.

The government’s efforts to improve the system have been piecemeal and half-hearted. Primary-care workers are now guaranteed a higher basic income, but are given less freedom to make extra money by charging patients for services and prescriptions. This has helped clinicians in poor areas, but in richer ones, where prescribing treatments had been more lucrative, it has left many staff worse off—particularly when they have to see more patients for no extra pay.

It would help if the government were to further reduce the pay gap between GPs and specialists. It is encouraging GPs to earn more money by seeing more patients and thus increase revenue from consultation fees. In big cities such as Beijing and Shanghai patients are being urged to sign contracts with their clinics in which they pledge to use them for referrals to specialists. In April the capital’s government raised consultation fees at hospitals, hoping to encourage people to go to community centres instead. Fearing a backlash, it has also pledged to reduce the cost to patients of drugs and tests.

Despite the government’s reforms, underuse of primary care has actually worsened. In 2013, the latest year for which data are available, GPs saw a third more patients than in 2009. But use of health-care facilities increased so much during that time that the share of visits to primary-care doctors fell from 63% of cases to 59% (the World Health Organisation says it should be higher than 80%, ideally). For poor rural households, health care has become even less affordable. And public anger has shown no sign of abating. Every year thousands of doctors are attacked in China—despite the police stations that have been opened in 85% of large-scale hospitals. It is not a healthy system.

——

May 12th, 2017 | China | 1142 words